Before the COVID-19 pandemic, nostalgia was a major force in global politics. Former US president Donald Trump rose to power in 2016 by promising to “make America great again,” and Brexiteers won their political battle partly by idealizing Britain’s imperial past.

While Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) called for a “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan pursued neo-Ottoman ambitions, and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban lamented the Kingdom of Hungary’s territorial losses after World War I.

These inclinations were suspended when the pandemic forced everyone to focus on a more immediate crisis, but now that COVID-19 is gradually fading in the rearview mirror, nostalgia has returned with a vengeance.

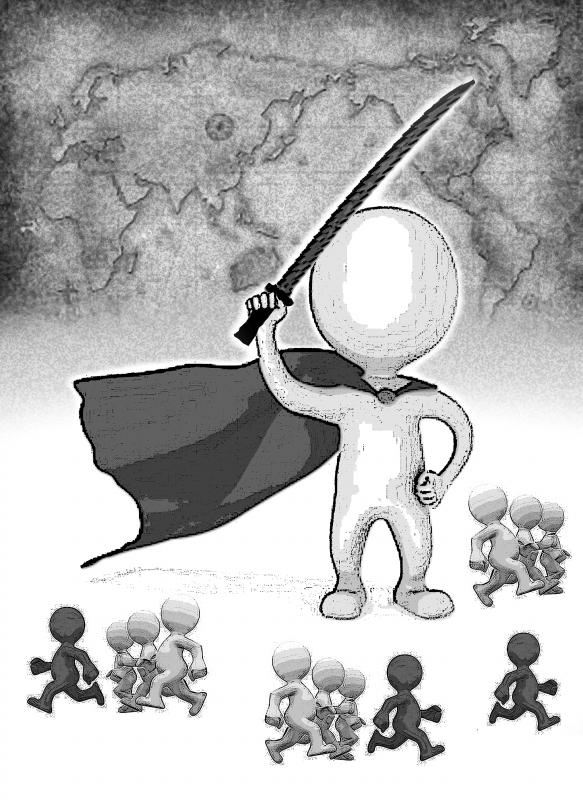

Illustration: Constance Chou

Russian President Vladimir Putin has taken this form of politics to an extreme by justifying his war of aggression against Ukraine on the false grounds that Russia’s neighbor “is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space.”

As is typical of nostalgia narratives, Putin’s account features a “golden age” followed by a “great rupture,” leading to a current state of discontent. The golden age was the Russian empire, of which Ukraine was a fully integrated satrapy. The rupture came when Vladimir Lenin created a federation of Soviet national republics out of the ethnic diversity of the former Russian empire.

According to Putin, it follows that “modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia.”

Finally, the current discontent is attributed to the persistence of this separation. As Putin said in March 2014: “Kyiv is the mother of Russian cities. Ancient Rus is our common source and we cannot live without each other.”

In many ways, nostalgic nationalism is the political malaise of our time. The Brexiteers were unwilling to accept Britain’s transformation into an ordinary medium-size country after centuries of imperial glory. The denouement of US liberal hegemony has also created opportunities for post-imperial powers such as China, Russia, Turkey, and even Hungary to reassert their lost status on the world stage, albeit with widely varying degrees of conviction and determination.

Trump tried to contain these centrifugal forces with his “America First” agenda, and his specter still haunts US politics.

Craving a return to bygone times is hardly innocuous. Sentimental, historically biased appeals to a romanticized past are the stock and trade of jingoistic leaders. Nostalgia becomes a tool for manipulating a polity’s perception of the present, setting the stage for radical and often dangerous policy shifts. Reviving moments of past glory can motivate a polity to test boundaries, take risks and defy the prevailing global order.

Nostalgia and nationalism are closely linked, especially in aging societies where a larger share of the population is more inclined to idealize the past.

Russian-American cultural theorist Svetlana Boym identifies two distinct types of nostalgia: reflective and restorative. Reflective nostalgia is generally benign. It scrutinizes the past critically, recognizing that while some good things have been lost, much has also been gained along the way. By contrast, restorative nostalgia — the dominant form today — seeks to rebuild what was lost.

For all the obvious differences between Brexit and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, both represent attempts to break from an unpleasant present by turning back the clock. The Brexiteers want to return to the Edwardian age, or at least to the 1970s, before Britain joined the European project; and Putin wants to return to the czarist era.

However, the politics of nostalgia varies significantly between democratic and authoritarian settings. Unlike Putin, the Brexiteers had to persuade a majority of voters to support their cause. In democracies, mainstream parties can challenge nostalgic populist movements’ effort to monopolize the country’s history. They can confront restorative nostalgia with reflective nostalgia, pointing out, for example, that the British empire had plenty of blood on its hands. Instead, the Remain camp’s technocratic “now and here” strategy amounted to bringing charts and graphs to a flag fight.

In authoritarian systems, where the opposition — if it exists at all — cannot respond openly to a regime’s historical claims, nostalgia becomes more dangerous, especially when its emotional appeal fuels the leader’s own solipsism. In these cases, one of the only solutions is international engagement with the alienated power to help it alleviate its sense of loss.

Such an approach might also be necessary for a re-emerging power such as China, which feels that the world is keeping it marginalized and not paying due respect to its long history. Unlike declining powers, though, an ascendant power can draw spiritual succor from the promise of restoring a lost homeland. That is why Xi often asserts a continuity in Chinese history, linking the ancient imperial past to the People’s Republic of China.

The idea of a great rejuvenation provides a roadmap to a better future without the need for a rupture with the present.

Edoardo Campanella is a senior fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they