The invasion of Ukraine is causing a mass exodus of companies from Russia, reversing three decades of investment by Western and other foreign businesses there following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The list of companies cutting ties or reviewing their operations is growing by the hour as foreign governments ratchet up sanctions against Russia, close airspace to its aircraft and lock some banks out of the SWIFT money messaging system. Some companies have concluded that the risks, both reputational and financial, are too great to continue. Operating in Russia has become deeply problematic.

The ruble plunged as much as 30 percent on Monday after the US banned transactions with the Bank of Russia, hindering its ability to deploy its US$630 billion foreign reserves to defend the currency.

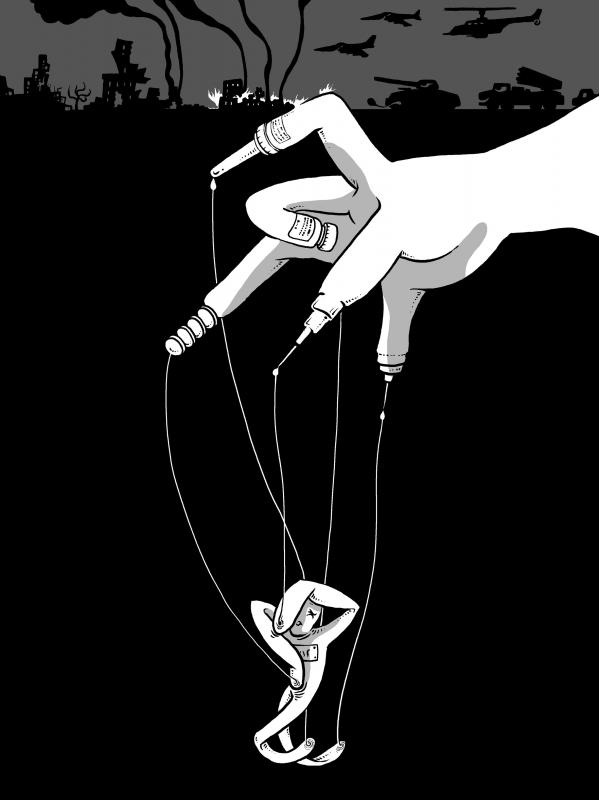

Illustration: Mountain People

For some companies, the decision to exit Russia is the conclusion of decades of lucrative, if sometimes fraught, investments. Foreign energy majors have been pouring in money since the 1990s. Russia’s largest foreign investor, BP PLC, led the way with its surprising announcement on Sunday that it would exit its 20 percent stake in state-controlled Rosneft, a move that could result in a US$25 billion write-off, and cut its global oil and gas production by one-third.

The stake was the product of a protracted battle in 2012 for control over TNK-BP, a joint venture between the oil giant and a group of billionaires. BP is now weighing whether to sell its stake back to Rosneft, people familiar with the matter said.

Shell PLC followed on Monday.

Citing Russia’s “senseless act of military aggression,” it said it is ending partnerships with state-controlled Gazprom, including the Sakhalin-II liquefied natural gas facility and its involvement in the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project, which Germany blocked last week. Both projects are worth about US$3 billion.

British Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Kwasi Kwarteng met with Shell CEO Ben van Beurden on Monday to discuss the company’s involvement and welcomed the move.

“Shell have made the right call,” Kwaterng wrote on Twitter. “There is now a strong moral imperative on British companies to isolate Russia. This invasion must be a strategic failure for [Russian President Vladimir] Putin.”

Equinor ASA, which is Norway’s biggest energy company and majority owned by the state, also announced it would start withdrawing from its joint ventures in Russia, worth about US$1.2 billion.

“In the current situation, we regard our position as untenable,” Equinor CEO Anders Opedal said.

On Tuesday, Exxon Mobil Corp said it would “discontinue” its Sakhalin-1 operations in Russia as international pressure grows to isolate the country’s economy.

The process to discontinue the operation will be “carefully” conducted with its partners, it said in a statement.

The moves left TotalEnergies SE as the only major energy firm to have significant drilling operations in Russia.

TotalEnergies on Tuesday said it would no longer provide capital for new projects in Russia, but did not go as far as other oil majors in responding to political pressure to economically isolate the country, as the French government signaled it was up to the company to decide on its business moves.

TotalEnergies CEO Patrick Pouyanne told a conference on Thursday last week that he did not see Russia’s invasion having an impact on the company’s operations, because they are very far from the front.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if you see more announcements coming down the line about exits,” said Allen Good, sector strategist at Morningstar. “BP had extra pressure given the UK government. I’m not sure TotalEnergies will face the same pressures given that the relationship between France and Russia is different.”

When the Soviet Union fell apart, foreign companies saw enormous opportunities — a massive new market of millions of consumers, as well as minerals and oil — and poured in to buy, sell and partner with Russian firms.

With Russia’s invasion of neighboring Ukraine, that trend has come to a screeching halt. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the largest in the world, said it was freezing about US$2.8 billion of Russian assets and would come up with a plan to exit by March 15.

Major law and accounting firms are also taking stock and facing potentially an enormous fallout. Baker McKenzie is so far one of the few law firms to publicly state it would sever ties with several Russian clients to comply with sanctions.

The Chicago-headquartered company’s clients include the Russian Ministry of Finance and VTB, Russia’s second-largest bank, which has been hit with asset freezes and sanctions by the US, the UK and the EU. The law firm on Monday said that it was reviewing its operations in Russia.

“We do not comment on the details of specific client relationships, but this will mean in some cases exiting relationships completely,” a Baker McKenzie spokesperson said.

London-based Linklaters said in a statement it was “reviewing all of the firm’s Russia-related work.”

Some of the largest law firms in London — including Allen & Overy and Clifford Chance — either failed to answer queries over the handling of their Russian clients or declined to comment. London courts have long been a battleground for wealthy Russians seeking to resolve disputes over business deals gone awry and failed marriages. British judges promise a justice system that affords even suspicious money a fair hearing in the event of disputes.

Other firms have come under fire for not getting out entirely. McKinsey & Co’s global managing partner Bob Sternfels took to LinkedIn on Sunday to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine and declare that the firm would no longer do business with any government entity in Russia. However, he is not pulling out. For some inside and outside the company, his move was insufficient.

The consultancy’s most senior executive in Ukraine called on companies to go further, and begin, where possible, shutting “offices and outlets” in Russia, where McKinsey has operated for nearly 30 years.

Andrei Caramitru, whose LinkedIn profile states that he was a senior partner at the firm for 16 years, tore into the McKinsey decision.

“You should be ashamed. You REFUSE to close the McKinsey office in Moscow,” Caramitru wrote in a LinkedIn post addressed to Sternfels. “Close it down! Now! It’s blood money, on your hands, staining you with each day that you keep it open.”

Pressure on others with sales and joint ventures in Russia is mounting. Daimler Truck Holding AG, one of the world’s largest commercial vehicle manufacturers, said it would stop its business activities in Russia until further notice and might review ties with local joint-venture partner, Kamaz PJSC.

Labor representatives said they “consider it appropriate” for the world’s largest truck maker to also offload its shares in Kamaz, the company’s works council said in an e-mailed statement.

Volvo Car AB and Volvo AB, the truck maker, also announced they were halting sales and production in Russia.Harley-Davidson Inc said in a statement it has suspended its business in Russia, which, along with the rest of Europe and the Middle East, accounted for 31 percent of its motorcycle sales last year. The Milwaukee, Wisconsin-based manufacturer does not break out sales to Russia alone.

General Motors Co (GM) said it was halting shipments to Russia, citing “a number of external factors, including supply chain issues and other matters beyond the company’s control.” GM exports about 3,000 vehicles a year to Russia from the US. In Japan, most of the major automakers said business with Russia would remain as is, though Mitsubishi Motors Corp said it would meet to assess the risk of operating there.

Others who have said little are seeing their stock prices plummet. French automaker Renault SA fell as much as 12 percent on Monday on how sanctions would hurt its business in Russia, its second-biggest market.

Its unit AvtoVaz, where Renault holds a 68 percent stake, makes Lada-brand vehicles that command about one-fifth of the Russian market. Renault also makes Kaptur, Duster and other vehicles at its own plant in Moscow.

Ford Motor Co said it was not planning to pull out of its joint venture in Russia with Sollers to produce commercial vans, at least not yet.

“Our current interest is entirely on the safety and well-being of people in Ukraine and the surrounding region,” Ford said in a statement. “We won’t speculate on business implications.”

Some companies are temporarily shuttering their operations in Ukraine, not Russia, saying they have concerns over safety as the invasion proceeds. Among others, Coca-Cola has said that its European bottling partner, Coca-Cola HBC AG, was idling production in Ukraine. It did not respond to questions regarding Russia.

“The safety of our people is our number one priority and we have enacted our contingency plans that include stopping production in the Ukraine, closing our plant and asking colleagues in the country to remain at home and follow local guidance,” a Coca-Cola HBC spokesperson said in a statement.

In a move that would reverberate well beyond the business community, world soccer body FIFA and the European authority UEFA banned Russian teams from games.

“Football is fully united here and in full solidarity with all the people affected in Ukraine,” they said in a joint statement.

A boycott of one of Russia’s most iconic products, vodka, is also brewing, with at least three US governors ordering the removal of Russian-made or branded spirits from stores. One of the largest alcohol chains in New Zealand pulled thousands of bottles of Russian vodka from stock — filling the empty shelves with Ukrainian flags.

Mark McNamee, Europe director at advisory firm FrontierView, was in Moscow two weeks ago talking to executives on the potential fallout of an invasion. Many shrugged off the worst scenarios, which means they were not necessarily prepared for what has transpired, he said.

Many corporations will have a difficult time supporting local operations given the SWIFT ban and capital controls, he said. Firms in the energy or commodities sectors or those selling to the Russian government face the potential risk of being perceived as “profiting from the war,” he added.

Consumer goods companies with extensive operations and local production in Russia cannot easily get out, even if they want to, but face financial turmoil. Before the invasion last week, Danone SA, which runs Russia’s largest dairy business and has been operating in Ukraine for more than 20 years, said it was putting additional plans in place to prepare for any military escalation.

Danone chief financial officer Juergen Esser said the company was trying to buy more local ingredients for its products from both markets, where the vast majority of raw materials are already domestically sourced. Nestle also hedged its currency exposure, he said. Danone entered the Russian market three decades ago. The country accounts for about 5 percent of the company’s net sales, and Ukraine less than 1 percent.

Carlsberg A/S is the largest brewer in Russia through its ownership of Baltika Breweries. The majority of Baltika’s supply chain, production and customers are based in the country, which limits the direct impact of many sanctions, a Carlsberg spokesperson said. The company has limited export from and imports to Russia, where Carlsberg employs 8,400 people, but it is currently not possible to estimate the full extent of the direct or indirect consequences from sanctions, she said. It employs 1,300 workers in Ukraine, where last week it halted operations at its breweries and sent workers home.

Foreign companies could face pushback from the Russian government, which could encourage boycotts or — in an extreme case — move to seize assets, McNamee said.

“If you have iconic brands from Italy, Germany, UK and America, you’re ripe for retaliation by the Russian government,” he said.

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) concludes his fourth visit to China since leaving office, Taiwan finds itself once again trapped in a familiar cycle of political theater. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has criticized Ma’s participation in the Straits Forum as “dancing with Beijing,” while the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) defends it as an act of constitutional diplomacy. Both sides miss a crucial point: The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world. The disagreement reduces Taiwan’s

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is visiting China, where he is addressed in a few ways, but never as a former president. On Sunday, he attended the Straits Forum in Xiamen, not as a former president of Taiwan, but as a former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman. There, he met with Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Chairman Wang Huning (王滬寧). Presumably, Wang at least would have been aware that Ma had once been president, and yet he did not mention that fact, referring to him only as “Mr Ma Ying-jeou.” Perhaps the apparent oversight was not intended to convey a lack of