Ownership of Australia’s newspapers is one of the most concentrated in the world, but changes in how media companies measure their audience figures make it difficult to get an up-to-date picture.

Former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd’s petition calling for an inquiry into media diversity, particularly the Murdoch-owned sections of the media, and the subsequent announcement of an Australian Senate inquiry into media diversity, have again focused attention on the state of Australia’s media industry.

It is worth taking a new look at how concentrated the ownership of Australian media is, and how it compares to other countries around the world.

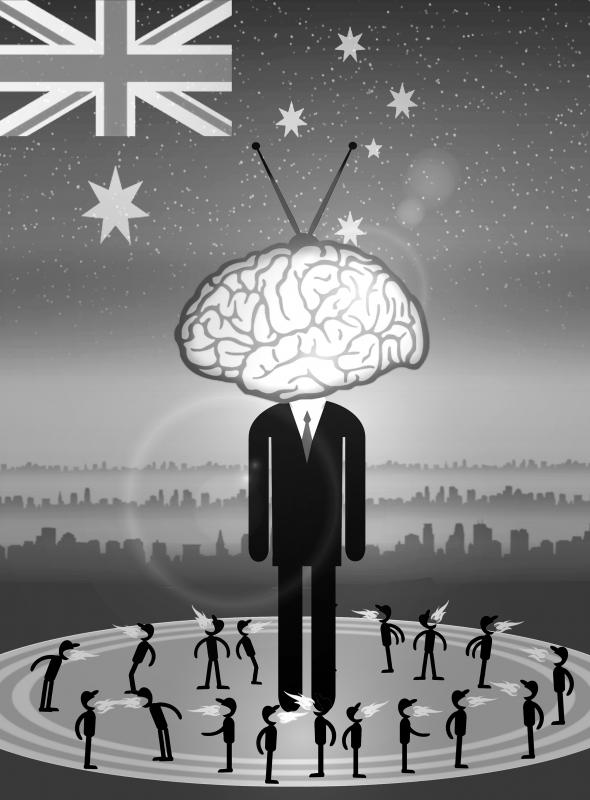

Illustration: Yusha

In 2016, a landmark study on media ownership and concentration — titled “Who Owns the World’s Media?” — was published. The study was a collaboration between academics in 30 countries, and it collated and analyzed data on the ownership and concentration of media in each nation.

For each country, the researchers calculated a number of different measures of market concentration across 13 media industries. They looked at which companies controlled how much of any given market using various measures of concentration.

One key measure is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which sums the square of the market share of all companies in the market to give an index ranging from 0, the least concentrated, to 10,000, which indicates a monopoly — a market dominated by single owner.

The research further differentiated “content media” — newspapers, magazines, books, radio, TV and film — and “platform media,” which consists of sectors like telecom and Internet service providers.

The results show that in 2011 Australia had the most concentrated newspaper industry out of any country studied, with the exception of China and Egypt.

Australia’s content media industry as a whole was also highly concentrated and had been getting steadily more concentrated over time.

The authors described the combination of high concentration with an upward trend as “problematic,” highlighting Australia alongside Switzerland, the Netherlands, Italy, Turkey, France and Russia.

Australia had the 10th-most concentrated content media industry by this measure and was very close to the global average. It is also worth pointing out that the media of several of the countries that ranked more highly are largely state-owned, such as in China and Egypt.

The high newspaper industry ownership concentration was largely due to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, which, at the time, controlled 57 percent of the newspaper market by circulation.

So what has happened since then? What does the industry look like this year?

Rodney Tiffen from the University of Sydney was one of the Australian researchers on the 2016 study and said he is unaware of any similar global comparisons since.

“The basic issue of concentration, the structural issue, has been fairly constant in news media for some decades,” he said. “But it has been made worse by how — in [former Australian prime minister] Malcolm Turnbull’s words — how increasingly propagandistic News Corp has become.”

Despite the announcement of a Senate inquiry, Tiffen is not sure how the situation could be improved.

“I can’t see any official policies doing much to improve the situation,” he said. “The structural issues are immovable, and the cultural issues are not things that governments can do much about.”

Since the “Who Owns the World’s Media” research was carried out, APN News & Media was bought by News Corp in December 2016, further concentrating ownership.

In 2018, the takeover of Fairfax Media by Nine increased concentration again, until Nine sold regional and community newspaper group Australian Community Media (AMC).

To get a current picture of media ownership concentration it is possible to work out the HHI based on the most recent data available and also to look at the percentage of the market covered by the top four companies.

However, the newspaper industry no longer reports circulation and now reports “average issue readership” for print, which uses survey data to estimate the average number of people who read each single “issue” of a given newspaper.

While this is not the same as circulation, it can be used as a reasonable proxy to approximate market share.

Based on these figures, the newspaper industry is still highly concentrated, with an HHI of 3,280, and News Corp has more than half of the market at 52 percent.

As the figures are not measuring circulation, it is not possible to measure them directly against the results of the 2016 study.

However, it is a good indication that the industry remains highly concentrated and is probably at the higher end in a global comparison.

It is also possible to measure market share by revenue, which is what industry market research company IBISWorld does. News Corp has 53.3 percent of the newspaper market by revenue, and if you compare the distribution of the top four companies across newspapers, radio and TV, News Corp’s market share is a clear outlier.

In both radio and television, the largest player has only 26 and 27 percent of the market respectively.

The online news market is much more diverse when looking at market share by audience, with an HHI score of 1,739.

Here, while News Corp has the highest market share, it is almost half of the market share of print newspapers at 26 percent.

Putting all of this together, Tiffen suggested that as newspaper circulation continues to decline, the dominance of News Corp would have less impact nationally.

“When you look at print, you’re getting increasing concentration with smaller reach. It’s a shrinking total market, but within that market the biggest fish are still getting bigger,” he said.

However, while the online news sector is more diverse, it has yet to replace the local reporting done by regional and community newspapers.

“I do think the advent of Guardian, Crikey, the Conversation, Inside Story, these sorts of things have enriched what is available, but their reach and penetration into wider society is not anything like what used to exist,” Tiffen said.

“There’s actually a lot of good professional [journalistic] work going on, but in many ways the gap between information rich and information poor is growing rather than narrowing,” Tiffen added.

Notes:

Print HHI and market share was calculated using “average issue readership” figures from the Enhanced Media Metrics Australia database for the period covering July last year to June. These data include 209 metropolitan, regional and community newspapers, and Sunday editions. The Saturday edition figures for mastheads were excluded. Ownership was assigned for all newspapers where possible.

News Web site HHI and market share was calculated using Nielsen’s unique audience figures for September, which covers 59 Web sites.

I have counted any site that has an Australian-specific home page or edition and a substantial editorial staff presence in Australia.

Audience and readership figures both include duplicate “readers” when summed to produce market share percentages, unlike the calculation of market share via circulation.

However, as circulation is no longer available, and revenue figures are not available for smaller companies, I have used readership as a proxy for circulation.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a