At first glance, things seem to be getting better for Japanese women.

In an economy that has historically lagged other developed nations when it comes to female workforce participation, a record 71 percent are now employed, an 11 percentage point leap over a decade ago.

The Japanese government boasts one of the most generous parental leave laws in the world, and has created a “limited full-time worker” category aimed primarily at mothers looking to balance job and family, while one of the most important needs for working families — daytime childcare — is slowly being expanded.

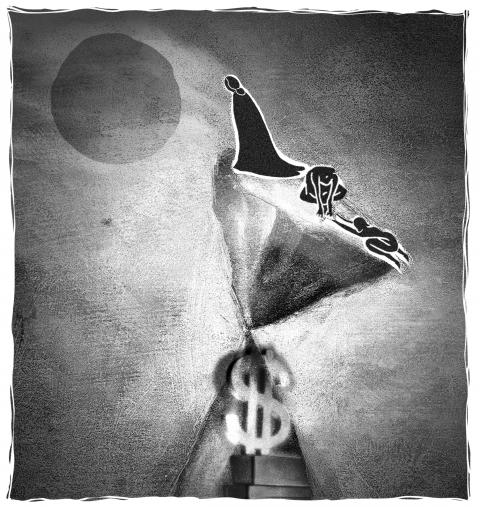

Illustration: Angela Chen

However, even with these advantages, Japanese women — whether single or married, full-time or part-time — face a difficult financial future.

A confluence of factors that include an aging population, a falling birthrate and anachronistic gender dynamics are conspiring to damage their prospects for a comfortable retirement.

International University of Health and Welfare professor Seiichi Inagaki said that the poverty rate for older Japanese women is to more than double over the next 40 years to 25 percent. For single, elderly women, he estimated that the poverty rate could reach 50 percent.

In Japan, people live longer than almost anywhere else and the birthrate is at its lowest level since records began. As a result, the nation’s working-age population is projected to have declined by 40 percent in 2055.

With entitlement costs skyrocketing, the Japanese government has responded by scaling back benefits, while proposing to raise the retirement age.

Some responded by moving money out of low-interest bank accounts and into tax-qualified, defined-contribution pension accounts, hoping investment gains might soften the blow, but such a strategy requires savings and women are less likely to have any.

Japan’s gender pay gap is one of the widest among advanced economies. Japanese women make only 73 percent that of men, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Japan’s demographic crisis is making matters worse: Retired couples who are living longer need an additional US$185,000 to survive projected shortfalls in the public pension system, a government report said.

A separate study did the math for Japanese women: They would run out of money 20 years before they die.

The dire pension calculations published by the Japanese Financial Services Agency in June last year caused such an outcry that the government quickly rejected the paper, saying it needlessly worried people, but economists said that the report was correct: Japan’s pension system is ranked 31st out of 37 nations due in part to underfunding, according to the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index.

Hitotsubashi University Institute of Economic Research professor Takashi Oshio said that private pensions and market-based retirement investments are now much more important than they once were.

Japan Women’s University professor Machiko Osawa was more blunt: The days of being “totally dependent on a public pension” are over.

However, there are additional obstacles for Japanese women.

Although 3.5 million have entered the workforce since Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office in 2012, two-thirds are working part-time.

Japanese men generally see their compensation rise until they reach 60. For women, average compensation stays largely the same from their late 20s to their 60s, mainly due to pauses in employment tied to having children or part-time, rather than full-time, work.

Since the mid-2000s, part-time employment rates have fallen for women in more than half the nations that make up the OECD, but in Japan the trend is reversed, with part-time work among women rising over the past 15 years.

One of Abe’s stated goals is to encourage more women to keep working after giving birth, part of his “Womenomics” initiative, but a government study showed that almost 40 percent of women who had full-time jobs when they became pregnant subsequently switched to part-time work or left the workforce.

Machiko Nakajima’s employment trajectory is typical of this state of affairs.

Nakajima, who used to work full-time at a tourism company, left her position at 31 when she became pregnant.

“I had no desire to work while taking care of my child,” she said.

Instead, Nakajima spent a decade raising two children before returning to work.

Now 46, the mother of two works as a part-time receptionist at a Tokyo tennis center. Though her husband, who also is 46, has a full-time job, Nakajima said that she fears for her future, given the faltering pension system.

“It makes me wonder how I’m going to live the rest of my life,” she said. “It’s not easy to save for retirement as a part-time worker.”

The monthly cost of living for a Japanese household with more than two people is ¥287,315 (US$2,607), according to government data.

About 15.7 percent of Japanese households live below the poverty line, which is about US$937 per month.

More than 40 percent of part-time working women earn ¥1 million or less per year, Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications data showed.

The lack of benefits, job security and opportunity for advancement — hallmarks of full-time employment in Japan — make such women financially vulnerable, particularly if they do not have a partner with whom to share expenses.

Japan Institute for Labor Policy & Training researcher Zhou Yanfei (周燕飛), author of a book on the subject titled Japan’s Married Stay-at-Home Mothers in Poverty, said that there is a gap of ¥200 million in lifetime income between women who work full-time and women who switch from full-time to part-time work at 40.

“It’s not easy to save for retirement as a part-time worker,” Zhou said.

Single mothers need to make at least ¥3 million a year — a number you cannot hit “if you work part-time,” she said.

In Japan, public pensions account for 61 percent of income among elderly households. The system provides basic benefits to all citizens and is funded by workers aged 20 to 59 — and by government subsidies. Many retirees get additional income from company pension plans.

While widows can claim some portion of a deceased spouse’s pension, the number of unmarried Japanese is steadily rising, having more than tripled since 1980. The latest survey showed that the rate for women is 14 percent compared with 23 percent for men.

One “reason why women’s retirement savings are lower than men’s is that the lifetime salary is low,” Alpha and Associates Inc president and financial planner Yoshiko Nakamura said. “Traditionally, many women chose to limit their workload to take advantage of social security spousal benefits, and that created many ‘women’s jobs’ that pay less than ¥1 million.”

Japan has historically created incentives for married women to limit their employment to such non-career-track jobs — lower pay means they (and their husbands) can take advantage of spousal deduction benefits. For example, the Japanese government gives a ¥380,000 tax deduction to a male worker if his wife earns less than about ¥1.5 million per year.

The private sector does it, too.

Many companies give employees a spousal allowance as long as their partner earns less than a certain amount. About 84 percent of Japanese private companies offer workers about ¥17,282 per month as long as their spouse earns less than a certain amount — usually about ¥1.5 million per year.

Yumiko Fujino, who works as an administrative assistant, should have been happy when the government raised the minimum wage, but she was not — for her husband to keep receiving spousal benefits, she had to cut back on her hours.

These limits are known among married women in Japan as the “wall.”

Unless a wife is making enough money on a part-time basis to afford income taxes and to forgo spousal benefits, it does not make sense to work additional hours, but to work those kind of hours means less time for the children, which is usually the point of working part-time in the first place.

Women who qualify for the spousal benefits “think less about retirement security and more about the current cost of living,” Fujino said.

The Japanese government is considering changes that would require more part-time workers to contribute to the pension program and mandate that smaller companies participate as well.

Keio University professor of economics Takero Doi said that the expansion would be a small step toward giving women a financial incentive to work more.

Former Japanese minister for gender quality Yoko Kamikawa agreed that the current pension system — last updated in the 1980s — should be expanded to include part-time workers.

Forty years ago, single-income households made up the overwhelming majority in Japan. Since then, families have become more diverse, Kamikawa said.

Osawa went farther, saying that social security should be based around individuals, not households.

“Marriage doesn’t last forever,” she said. “Women used to rely on their husbands for financial support, but now there’s the danger of unemployment and more men are in jobs where their pay doesn’t rise.”

However, one of the biggest reforms proposed by Abe, “limited full-time worker” status, does not always work as advertised.

“Limited full-time” employees often face the same workload they would if they were full-time.

Junko Murata, 43, a mother of two, said juggling both work and taking care of her children proved too difficult, so she eventually returned to a part-time job.

While an increasing number of companies have been giving women the opportunity to work more flexible hours after they return from maternity leave, some women complain of being marginalized, with few opportunities for career growth and advancement.

A Japanese government survey released last year offered a bleak outlook. It showed no improvement in gender equality in the workplace, with about 28.4 percent of women saying they were treated equally at work, up only 0.2 percentage points since 2016.

Yasuko Kato, 42, returned to work as a part-time accountant three years ago, but said there has been little change in her responsibilities.

Because she drops off and picks up her children from school, she works from 9am to 4:30pm.

“I have no extra time at work,” she said.

However, because of a chronic staff shortage, she does not get any help from full-time employees.

As a result “it’s difficult to raise my hand for a new role,” Kato said.

Additional reporting by Isabel Reynolds, Lisa Fleisher and Kurumi Mori

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then