As Hong Kong’s historic protests become increasingly violent, mainland Chinese living in the territory are becoming increasingly fearful.

Min, who moved to Hong Kong from the mainland in 1995 and now runs his own hedge fund, said the startling escalation in mayhem prompted him to tell his children not to speak Mandarin in public for fear they will get beaten up in the Cantonese-speaking territory.

Before going out for dinner, Min checks his phone for news on which streets are blocked due to mass marches or violent clashes. He stopped flying on the territory’s flagship carrier, Cathay Pacific Airways, where some staff took part in protests and others were fired after investigations into depleted oxygen tanks.

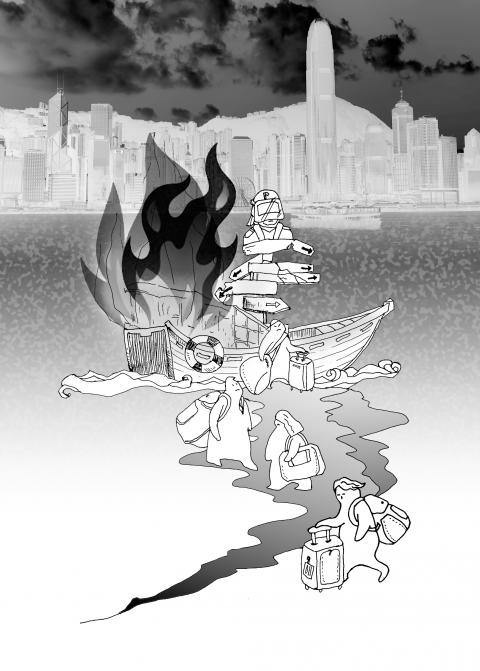

Illustration: Tania Chou

With battles between police and black-clad mobs becoming pervasive, Min said he has considered moving his business to Shanghai and his family to Canada.

“They have no moral bottom line as to what they’ll do to achieve their goals,” Min, who asked that his full name not be used for fear of retribution, said of the protesters. “Fingers crossed, I believe the police can crush this.”

The strife ripping through Hong Kong — with police officers and protesters in hand-to-hand combat, subway stations set ablaze and an improvised explosive device detonated near a police car — looks very different from the territory’s mainland-born residents.

More than 1 million Mainlanders, including many professionals, have migrated across the border since China regained control of the former British colony in 1997, helping swell its population to 7.5 million.

The protests began in opposition to a since-scrapped government bill allowing extraditions to mainland China and have expanded to include calls for greater democracy and an independent inquiry into police tactics.

While the majority of protesters are peaceful, the demonstrations often feature a darker, anti-China tone. Some demonstrators have burned Chinese flags and spray-painted the phrases “Chinazi” and “Hong Kong is not China!” across the territory.

The rhetoric is spilling over into violence on both sides. A 22-year-old mainland visitor accused of slashing a teenage Hong Kong protester in the abdomen surrendered to police this week.

Over the weekend, gangs ransacked or destroyed Chinese bank branches and retail businesses, including an outlet for smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp based in Beijing.

The tensions between mainlanders and locals also surface in daily office interactions.

“Employees are generally encouraged to not discuss this topic at work and to leave political opinions at home,” said Benjamin Quinlan, chief executive officer of financial services consultancy Quinlan & Associates.

Still, “you can’t segregate a private and corporate life so cleanly, and there will inevitably be opinions on politics that don’t gel among colleagues,” he said.

When crowds surged into the streets recently, Yang, a 34-year-old finance professional from China, watched from above in one of the territory’s gleaming skyscrapers.

TVs in the office — and desktop livestreams — were all tuned to the protests against Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s (林鄭月娥) impending use of a colonial-era emergency powers law to ban face masks on demonstrators.

Mobile phones buzzed with messages flowing across WeChat groups about looming protests and violence outside, including one alarming video of a Chinese banker from JPMorgan Chase & Co getting punched in the head by a protester and someone yelling: “Go back to the mainland!”

On Tuesday, lawmakers debated the ban on face coverings at the Legislative Council. Hong Kong Financial Secretary Paul Chan (陳茂波) was also set to announce various measures to support local businesses impacted by the protests.

Yang, who asked to be identified only by one name, is also scared to speak Mandarin and has been regularly fleeing across the border to nearby Shenzhen to escape the violence. That Friday afternoon, she left early and dashed to meet her husband and daughter at the bus station, right before the territory descended into its worst violence on the weekend of Oct. 5.

“As I rushed to the bus station to regroup with my family, I was so stressed — hearing my heart beating quickly and strongly,” she said, adding she bought the last three tickets for a bus that whisked them all to Shenzhen, which was celebrating 70 years of Chinese Communist Party rule with buildings and billboards decked out in red lights.

“When the bus crossed the bridge and was about to enter Shenzhen, we all saw the red neon at the other side of the river. I felt suddenly relaxed,” she said.

At the same time, several mainlanders interviewed said they were reluctant to uproot the lives they have built in Hong Kong over many years: landing coveted jobs at international companies, getting their children into international schools and buying homes. Furthermore, plenty of Mandarin conversations are heard while walking through the financial district.

Yet while many mainlanders say they feel shunned by some Hong Kongers, many locals worry that showing support for the protests will hurt their careers. Some Hong Kong employees working at Chinese firms said they were told to attend pro-Beijing demonstrations and feared losing their jobs if they refused.

One Hong Konger with the surname Ho, who took a job at a US-based bank over the summer after working at a Chinese bank in the territory for three years, said mainland colleagues at her former employer would try to find out her stance on the conflict — and criticize anyone they thought supported the protesters.

“I was asked to attend the rallies that support the Hong Kong police,” said the employee, who asked not to be identified by her full name to avoid hurting her career. “Of course, I didn’t go. Then some of my former colleagues linked my resignation to my political views. They thought I was fired because I’m pro-independence, which wasn’t true.”

In the financial sector, the conflicts between those sympathetic to protesters and those aligned with Beijing are seen in instances both subtle and dramatic.

Hao Hong (洪灝), chief strategist at Bocom International Holdings Co in Hong Kong, recently visited another company to meet with workers from mainland China, stepping into an office and speaking to them in Mandarin. Their local colleague quickly raised the volume on a nearby TV, overpowering the conversation with the sound of a show — in Cantonese.

“Sometimes people refuse to talk to you if you speak to them in Mandarin,” said Hong, who has lived in the former British colony for eight years. “Everyone is touchy.”

In addition to not speaking Mandarin in public, other mainlanders said they have stopped using WeChat — the Tencent Holdings-owned Chinese messaging service — in the open.

Some have started considering relocating back to the mainland, despite spending decades in the territory, said one woman who works at a Chinese hedge fund and asked that she only be identified as Levy.

Mainlanders with children in local schools are concerned they will be exposed to anti-government sentiment, she said.

“We are all in the financial industry. If they can find good offers in Shanghai or Beijing, there is now a stronger incentive to move back,” Levy said.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Last week, Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) unveiled the location of Nvidia’s new Taipei headquarters and announced plans to build the world’s first large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer in Taiwan. In Taipei, Huang’s announcement was welcomed as a milestone for Taiwan’s tech industry. However, beneath the excitement lies a significant question: Can Taiwan’s electricity infrastructure, especially its renewable energy supply, keep up with growing demand from AI chipmaking? Despite its leadership in digital hardware, Taiwan lags behind in renewable energy adoption. Moreover, the electricity grid is already experiencing supply shortages. As Taiwan’s role in AI manufacturing expands, it is critical that