How did the world’s two most venerable and influential democracies — the UK and the US — end up with President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Boris Johnson at the helm? Trump is not wrong to call Johnson the “Britain Trump” (sic). Nor is this merely a matter of similar personalities or styles: It is also a reflection of glaring flaws in the political institutions that enabled such men to win power.

Both Trump and Johnson have what the Irish physicist and psychologist Ian Hughes calls “disordered minds.”

Trump is a chronic liar, purveyor of racism and large-scale tax cheat. Former US special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on his 22-month investigation of Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign described repeated cases of Trump’s obstruction of justice.

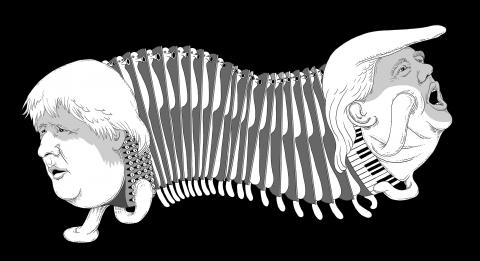

Illustration: Mountain People

Trump stands accused by more than 20 women of sexual predation — a behavior he bragged about on tape — and directed his attorney to make illegal payments of hush money that constituted campaign finance violations.

Johnson’s personal behavior is similarly incontinent. He is widely regarded as a chronic liar and unkempt in his personal life, which includes two failed marriages and an apparent domestic altercation on the eve of becoming prime minister. He has been repeatedly fired from jobs for lying and other disreputable behavior.

He led the Brexit campaign in 2016 on claims that have been proven false. As British secretary of state for foreign and Commonwealth affairs, he twice leaked secret intelligence — in one case, French intelligence about Libya, and in another case, British intelligence about Iran.

Like Trump, he has a high disapproval rating among all age groups, and his approval ratings rise with voter age.

Trump’s record in office presents a further political puzzle. His policies are generally unpopular and rarely reflect a majority of public opinion. His most important legislative victory — the 2017 tax cut — was unpopular at the time and remains so today.

The same is true of his positions on climate change, immigration, building a wall along the Mexican border, cutting social spending, ending key provisions of Obamacare, withdrawing from the Iran nuclear agreement and much else.

Trump’s approval rating is consistently below 50 percent and currently stands at about 43 percent, with 53 percent disapproval.

Trump uses emergency decrees and executive orders to implement his unpopular agenda. While the courts have overturned many decrees, the judicial process is slow, meandering and unpredictable. In practice, the US is as close to one-person rule as imaginable within its constitution’s precarious constraints.

The situation with Johnson might be similar.

Public opinion turned against Brexit, Johnson’s hallmark issue, after the withdrawal negotiations with the EU exposed the Leave campaign’s lies and exaggerations ahead of the 2016 referendum.

Although the public and a majority in UK Parliament strongly oppose a no-deal Brexit, Johnson has pledged just that if he fails to negotiate an alternative.

There is an obvious answer to the question of how two venerable democracies installed disordered minds in power and enabled them to pursue unpopular policies.

However, there is also a deeper one.

The obvious answer is that both Trump and Johnson won support among older voters who have felt left behind in recent decades.

Trump appeals especially to older white male conservatives displaced by trade and technology, and, in the view of some, by the US’ movements for civil rights, women’s rights and gay rights.

Johnson appeals to older voters hit hard by deindustrialization and to those who pine for Britain’s glory days of global power.

However, this is not a sufficient explanation.

The rise of Trump and Johnson also reflects a deeper political failure. The parties that opposed them, the Democrats and Labour respectively, failed to address the needs of workers displaced by globalization, who then migrated to the right.

Yet Trump and Johnson pursue policies — tax cuts for the rich in the US, a no-deal Brexit in the UK — that run counter to the interests of their base.

The common political flaw lies in the mechanics of political representation, notably both countries’ first-past-the-post voting systems.

Electing representatives by a simple plurality in single-member districts has fostered the emergence of two dominant parties in both countries, rather than the multiplicity of parties elected in the proportional representation systems of western Europe.

The two-party system, which then leads to a winner-take-all politics, fails to represent voter interests as well as coalition governments, which must negotiate and formulate policies that are acceptable to two or more parties.

Consider the US situation.

Trump dominates the Republican Party, but only 29 percent of Americans identify themselves as Republicans, 27 percent as Democrats and 38 percent as independents, not comfortable with either party, but unrepresented by an alternative.

By winning power within the Republican Party, Trump scraped into office with fewer votes than rival and former US secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton, but with more Electoral College delegates.

Given that only 56 percent of eligible Americans voted in 2016 (partly owing to deliberate Republican efforts to make voting difficult), Trump received the support of just 27 percent of eligible voters.

Trump controls a party that represents less than one-third of the electorate and governs mostly by decree.

In the case of Johnson, fewer than 100,000 Conservative Party members elected him as their leader, thus making him prime minister, despite his approval rating of just 31 percent (compared with 47 percent who disapprove).

Political scientists predict that a two-party system will represent the “median voter,” because each party moves to the political center in order to capture half the votes plus one.

In practice, campaign financing has dominated US party calculations in recent decades, so the parties and candidates have gravitated to the right to curry favor with rich donors. (US Senator Bernie Sanders is trying to break the chokehold of big money by raising large sums from small donors.)

In the UK, neither major party represents the majority who oppose Brexit. Yet the UK political system may nonetheless enable one faction of one party to make historic and lasting decisions for the country that most voters oppose.

Most ominously, winner-take-all politics has enabled two dangerous personalities to win national power despite widespread public opposition to them.

No political system can perfectly translate the public will into policy, and the public will is often confused, misinformed or swayed by dangerous passions.

The design of political institutions is an ever-evolving challenge. Yet today, owing to their antiquated winner-take-all-rules, the world’s two oldest and most venerated democracies are performing poorly — dangerously so.

Jeffrey Sachs, a professor of sustainable development and a professor of health policy and management at Columbia University, is director of Columbia’s Center for Sustainable Development and of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they