It is China’s Web giant and has a string of high-profile investments spanning Snapchat, Spotify, Tesla, and Hollywood film and TV.

It is a sprawling corporate giant that has overtaken Facebook to become the world’s fifth-most valuable listed company — but few, in the West at least, will have heard of Tencent, even though it is worth half a trillion US dollars and rising.

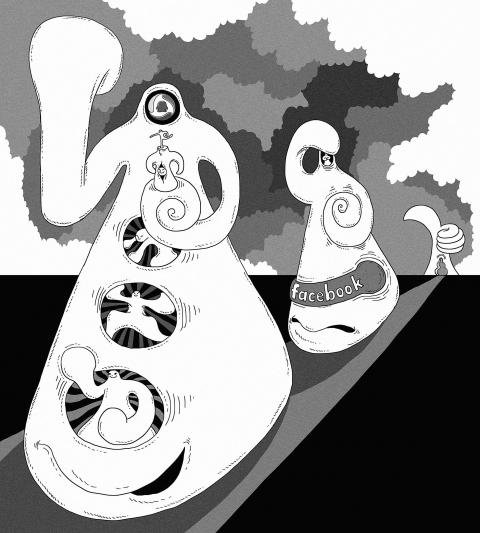

China is the world’s most populous digital market and the protection afforded by state censorship through the so-called “Great Firewall” — which has meant no competition from Facebook, Google, Twitter and Netflix — has helped Tencent flourish since it launched nearly two decades ago in Shenzhen, China.

Illustration: Mountain people

However, in the past year its shares have been supercharged — climbing from less than HK$200 at the beginning of last year to HK$448 now — and the value of the company has soared.

There are three cornerstones of Tencent’s business: its messaging app WeChat, the biggest mobile gaming franchises in the world and an ecosystem built around its 1 billion users that apes many of the services offered by the Silicon Valley firms that do not operate in China.

The company’s Netflix-style Tencent Video service — the biggest in China, with exclusive content including US National Football League games and HBO series such as Game of Thrones — more than doubled in size in the past year, attracting more than 40 million paying subscribers.

“They have a relationship of mutual benefit with the Chinese state,” Enders analyst Jamie McEwan said. “They have been allowed to grow and massively diversify their businesses without the level of scrutiny or competition you might see in Western countries.”

Late last year, Tencent became the first Chinese firm to pass the US$500 billion stock market valuation mark, supplanting Facebook as the world’s fifth-biggest firm, a bittersweet moment for company cofounder Ma Huateng (馬化騰), 46, also known as “Pony” Ma.

Tencent in 2014 was on the brink of buying WhatsApp, which would have made it a global power player overnight. The company was close to a deal when talks had to be delayed so that Ma could undergo back surgery. A panicked Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg got wind of the move and swooped, tabling an enormous US$19 billion rival bid — by far Facebook’s biggest deal and more than twice the offer made by Tencent — to see off the threat.

Thwarted, but undeterred, Ma late last year took a 12 percent holding in Snapchat — he had made a small investment in 2013 — in a busy year that also included buying 5 percent of Elon Musk’s electric car firm Tesla and swapping minority stakes in its music streaming business with Spotify.

Tencent Music, which dwarfs efforts by Apple and Spotify in China, is expected to make a US$10 billion stock market listing this year.

Tencent also cranked up its domination of mobile gaming, handing over US$8.6 billion for Finnish company Supercell, maker of two of the biggest games in the world, Clash of Clans and Clash Royale.

It also owns Los Angeles-based game maker Riot, behind the huge League of Legends franchise, and has stakes in Gears of War maker Epic and Activision Blizzard, home to Call of Duty, World of Warcraft and Candy Crush Saga.

Tencent also owns the most profitable game in the world, Honor of Kings, which makes about US$1 billion per quarter and has 200 million monthly players.

It has proved so addictive in games-mad China that the government last year warned Tencent in an article in the state-owned People’s Daily, saying it was “poison” and a “drug” that harms kids.

The risk of a government crackdown on one or more of Tencent’s golden geese — the company relies on gaming for more than 40 percent of its total revenue — spurred jittery investors to wipe nearly US$18 billion off its stock market value. Tencent swiftly introduced one-hour time limits for children younger than 12 and two hours for 12 to 18-year-olds.

Analysts estimate that Tencent’s digital services are used by more than two-thirds of the Chinese population. Chinese users collectively spend 1.7 billion hours per day on the company’s apps.

The business started in cramped Shenzhen offices in the late 1990s, swiftly developing a bad reputation for cloning digital products for the Chinese market, but it was the launch of WeChat in 2011 that supercharged the company’s strategy.

The WeChat ecosystem is so broad it is almost like rolling most of the apps on a typical Western user’s mobile phone into one.

“It is compared to WhatsApp or Facebook messenger, but it is not really,” said Wang Xiaofeng, a Singapore-based analyst with Forrester Research.

“It has payment systems, ‘smart’ city offerings such as the ability to schedule appointments at a bank, a doctor, pay traffic fines or make visa applications, and e-commerce,” she said.

Tencent’s ambition to be an essential part of digital daily life means it holds a dizzyingly diverse range of interests, including in Didi, China’s answer to Uber; the nation’s second-biggest e-tailer, JD.com; and Hike, a messaging service popular in India.

Last month, it even did an Amazon.com, which bought real-world retailer Whole Foods, taking a stake in one of China’s largest supermarket chains, Yonghui Superstores.

It also has a stake in Hollywood film distributor STX Entertainment, behind movies such as Bad Moms and All The Money in the World, while movie arm Tencent Pictures was a backer of blockbuster Kong: Skull Island.

“The ultimate goal of all their investments is to enhance the services they have already developed to support the ecosystem,” IHS Markit senior analyst Wang Ruomeng said.

The protected market conditions that have allowed Tencent to flourish and the vast differences between Chinese and foreign Internet users’ habits has seen the company struggle abroad. Seven years after launching WeChat, it is yet to break into any other market, although it has earmarked Malaysia.

Analysts believe a key focus will be on targeting the huge numbers of Chinese diaspora and tourists by making WeChat features like payments available overseas, rather than try and make the app a full-fledged Facebook rival. The payment system is already available in places such as Harrods and Selfridges.

“WeChat and Tencent tried aggressively expanding into international markets like South America, Europe and even the US, but it didn’t work out so well in mainstream Western markets, where existing players like WhatsApp are so established,” Wang Xiaofeng said. “Their global expansion will in some places target Chinese travelers, with different strategies in emerging markets like Southeast Asia.”

Tencent facts

It is ironic that a company worth more than US$500 billion happens to be called Tencent, which translates into English as “soaring information.”

Cofounder Ma Huateng is the 14th-richest person in the world with a fortune of nearly US$50 billion, one place below Google cofounder Sergey Brin.

Befitting its status as a global tech giant, the company is aping its Silicon Valley rivals with a new US$600 million twin-skyscraper headquarters building.

Tencent is one of three Chinese Internet behemoths, including Baidu and Alibaba, known collectively as BAT — China’s answer to Silicon Valley’s power club known as FANG: Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google.

Each year, every Tencent employee, more than half of whom are employed in research and design, is given the chance to participate in a company-wide singing competition and to “shine brightly on stage.”

Pony Ma is deputy of the Chinese National People’s Congress, politically useful in a nation renowned for cracking down on businesses that get offside with Beijing.

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

Taiwan People’s Party Legislator-at-large Liu Shu-pin (劉書彬) asked Premier Cho Jung-tai (卓榮泰) a question on Tuesday last week about President William Lai’s (賴清德) decision in March to officially define the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as a foreign hostile force. Liu objected to Lai’s decision on two grounds. First, procedurally, suggesting that Lai did not have the right to unilaterally make that decision, and that Cho should have consulted with the Executive Yuan before he endorsed it. Second, Liu objected over national security concerns, saying that the CCP and Chinese President Xi