Ten years ago, the world population was growing by 1.24 percent annually; today, the figure has dropped to 1.18 percent — an addition of about 83 million people per year. The overall growth rate, which peaked in the late 1960s, has been falling steadily since the 1970s.

The UN report attributes the slowdown to the near-global decline in fertility rates — measured as the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime — even in Africa , where the rates remain the highest.

However, that fall is being offset by countries in which populations are already large, or where high numbers of children are born. According to the study, nine countries are set to account for half the world’s population growth between now and 2050: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, the US, Indonesia and Uganda.

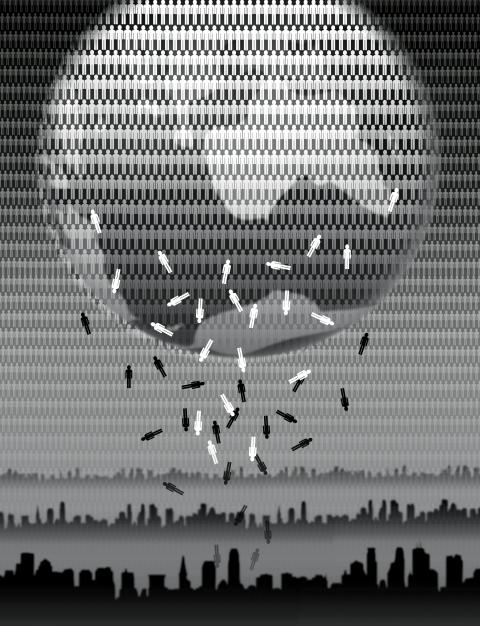

Illustration: Yusha

“Continued population growth until 2050 is almost inevitable, even if the decline of fertility accelerates,” says the report, World Population Prospects: the 2015 revision.

“There is an 80 percent probability that the population of the world will be between 8.4 and 8.6 billion in 2030, between 9.4 and 10 billion in 2050 and between 10 and 12.5 billion in 2100,” the report says.

By 2050, six countries — China, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan and the US — are expected to have populations of more than 300 million.

The report says that Africa alone is set to drive more than half of the world’s population growth over the next 35 years, during which time the population of 28 of the continent’s countries is set to more than double. It is predicted that by 2050, Nigeria’s population is set to surpass that of the US, making the west African nation the third most populous country in the world.

If current birthrate trends persist, Africa, which contains 27 of the world’s 48 least-developed countries, will be the only major area still experiencing substantial population growth after 2050. Consequently, its share of the global population is forecast to rise to 25 percent in 2050 and 39 percent by 2100. Asia’s share, meanwhile, is set to fall to 54 percent in 2050 and 44 percent in 2100.

“Regardless of the uncertainty surrounding future trends in fertility in Africa, the large number of young people currently on the continent who will reach adulthood in the coming years and have children of their own, ensures that the region will play a central role in shaping the size and distribution of the world’s population over the coming decades,” the report says.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs population division director John Wilmoth said the new projections laid bare the scale of the task facing the world as it prepares to agree the development framework for the next 15 years.

“The concentration of population growth in the poorest countries presents its own set of challenges, making it more difficult to eradicate poverty and inequality, to combat hunger and malnutrition, and to expand educational enrollment and health systems, all of which are crucial to the success of the new sustainable development agenda,” he said.

Wilmoth said that although the population growth rate had declined “gradually but steadily” since the 1970s, it had done so at different speeds in different parts of the world.

“Africa is currently the region of the world where population growth is still rather rapid due to continued high levels of fertility, but even there we see the sorts of changes that were predicted and expected in the sense that, once populations start to have a higher level of life expectancy, they also come to realize that there’s not the same need to produce as many children,” he said. “With increasing child survival, it just doesn’t make as much sense to have such large families as it did in the past.”

China, the world’s most populous country with 1.4 billion people, is expected to be overtaken by India — now at 1.3 billion — within the next seven years. From 2030, when its population is projected to reach 1.5 billion, India is likely to experience several decades of growth. China, on the other hand, is set to experience a slight decrease after the 2030s.

Of all the world’s major regions, only Europe can expect a steady decline in its population over the remainder of this century, with its total inhabitants expected to shrink from 738 million people now to 646 million in 2100.

Almost half the people in the world — 46 percent — live in countries with low levels of fertility, where women have fewer than 2.1 children on average during their lifetimes. Such countries include all of Europe and North America, 20 Asian countries, 17 Latin American or Caribbean ones, three in Oceania and one in Africa.

Another 46 percent live in “intermediate fertility” countries — such as India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mexico and the Philippines — where women have on average between 2.1 and five children.

The remainder live in “high-fertility” countries, where fertility declines have been limited and where the average woman has five or more children over her lifetime. All but two of the 21 “high-fertility” countries are in Africa; the largest are Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Uganda and Afghanistan.

The slowdown in population growth provoked by the overall fall in fertility is also set to cause the proportion of older people to increase over time: The number of older people in the world is projected to be 1.4 billion by 2030, 2.1 billion by 2050, and could rise to 3.2 billion by the turn of the next century.

In Europe, 34 percent of the population is predicted to be over 60 by 2050 — up from 24 percent today. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the proportion of people in the same age group is set to more than double to reach 25 percent by the middle of the century. The population of Africa, which has the youngest age distribution of any area, is set to age rapidly, with the proportion of people aged over 60 increasing from 5 percent today to 9 percent by 2050.

Although the report predicts that the global population is set to reach 8.5 billion in 2030, 9.7 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100, the UN acknowledges that its predictions could be skewed by slower-than-projected declines in fertility.

It currently estimates that global fertility is set to fall from 2.5 children per woman from 2010 to this year, to 2.4 between 2025 and 2030 and 2 from 2095 to 2100. Steep declines are also projected for the world’s least-developed countries, with the average dropping from 4.3 from 2010 to this year, to 3.5 between 2025 and 2030, and 2.1 from 2095 to 2100.

However, should fertility rates not decline along the predicted lines — if, for example, all countries had a rate that was half a child above the medium variant — the global population in 2100 could swell to 16.6 billion people, more than 5 billion more than the current estimate.

“To realize the substantial reductions in fertility projected, it is essential to invest in reproductive health and family planning, particularly in the least-developed countries, so that women and couples can achieve their desired family size,” the report says.

“In 2015, the use of modern contraceptive methods in the least-developed countries was estimated at around 34 percent among women of reproductive age who were married or in union, and a further 22 percent of such women had an unmet need for family planning, meaning that they were not using any method of contraception despite a stated desire or intention to avoid or delay childbearing,” the report says.

The latest projections are based on the previous report, the 2010 round of national population censuses and recent demographic and health surveys.

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

On Wednesday last week, the Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an article by Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) asserting the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) territorial claim over Taiwan effective 1945, predicated upon instruments such as the 1943 Cairo Declaration and the 1945 Potsdam Proclamation. The article further contended that this de jure and de facto status was subsequently reaffirmed by UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 of 1971. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs promptly issued a statement categorically repudiating these assertions. In addition to the reasons put forward by the ministry, I believe that China’s assertions are open to questions in international

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of