At 16, the gem trader’s son set out for the jade mines to seek his fortune in the precious stone that China craves. However, a month in, Sang Aung Bau Hkum was feeding his own addiction: heroin, the drug of choice among the men who work the bleak terrain of gouged earthen pits, shared needles and dwindling hope in the jungles of northern Myanmar.

Three years later, he finally found what he had come for: a jade rock “as green as a summer leaf.” He spent some of the US$6,000 that a Chinese trader paid him for the stone to pay for a motorcycle, a cellphone and gambling.

“The rest disappeared into my veins,” Bau Hkum said, tapping the crook in his left arm as dozens of other gaunt miners in varying states of withdrawal passed the time at a rudimentary rehabilitation clinic.

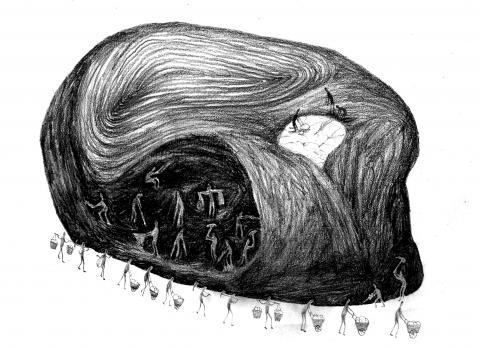

Illustration: Mountain People

“The Chinese bosses know we are addicted to heroin, but they don’t care. Their minds are filled with jade,” he said.

Bau Hkum, now 24, is just one face of a trade — like conflict diamonds in Africa — that is turning good fortune into misery.

Driven by an insatiable demand from the growing Chinese middle class, Myanmar’s jade industry is booming and should be showering the nation — one of the world’s poorest — with unprecedented prosperity. Instead, much of the wealth it generates remains in control of elite members of the Burmese military, the rebel leaders fighting them for autonomy and the Chinese financiers with whom both sides collude to smuggle billions of US dollars’ worth of the gem into China, according to jade miners, mining companies and international human rights groups.

Such rampant corruption has not only robbed Myanmar’s government of billions in tax revenue for rebuilding after decades of military rule, it has also helped finance a bloody ethnic conflict and unleashed an epidemic of heroin use and HIV infection among the Kachin minority who work the mines.

The drug and jade trades have become a toxic mix, with heroin — made from opium poppies that long ago turned Myanmar into a top producer of illicit drugs — keeping a pliant workforce toiling in harsh conditions as Burmese authorities and Chinese businesspeople turn a blind eye.

While Myanmar is experimenting with democratic governance after nearly 50 years of military rule, its handling of the jade industry has become a test of the new civilian leaders and their commitment to supporting human rights and rooting out corruption, as well as an early check on whether they will reject the former junta’s kleptocratic dealings with China.

So far, experts say, they have failed.

Washington is worried enough about the link between jade and violence — and the effect on democratic change — that it kept in place a ban on the gem from Myanmar, even after it suspended almost every other sanction against the nation since a civilian government came to power in 2011. However, critics say the sanctions are useless because China attaches no such conditions.

“The multibillion-dollar jade business should be driving peaceful development in Kachin and Myanmar as a whole,” said Mike Davis from Global Witness, an anticorruption organization. “Instead it is empowering the same elite that brought the country to its knees and poses the biggest threat to peace and democratic reform.”

POVERTY AMID RICHES

The fountainhead of Myanmar’s jade wealth is in the mountains of Kachin State, which is rich in natural resources and poor in just about everything else. The nation’s northernmost territory, Kachin shares a long border with China and is home to the Kachin ethnic group, a largely Christian minority with ambitions to gain autonomy from majority Buddhist Myanmar.

Myitkyina, the down-and-out state capital, is the gateway to the most active mining region, containing what experts say is the world’s biggest and most valuable trove of jade.

With its broken sidewalks, stray dogs and cemeteries littered with syringes, Myitkyina is a potent symbol of the region’s ills. The city’s tea shops have a thriving illegal side business in selling heroin, one of the few trades that have grown alongside the jade industry.

“In every house, there is an addict,” said Gareng Bang Aung, a local who uses heroin.

The city is the closest that Westerners can get to the mining area, Hpakant. The Burmese government says it keeps the area closed because of sporadic fighting with the Kachin rebel army, but activists see a darker purpose: hiding the illegal jade and drug trades flourishing there. The only foreigners allowed past the military checkpoints are Chinese who run the mines or go there to buy gems, activists say.

The lack of access adds to the mysteries of the jade industry, whose inner workings are deliberately obscured. Even the most basic information is not publicly available, including which companies operate the mines and how many are Chinese-run or financed despite laws banning foreign ownership. However, interviews with jade miners and executives in Myitkyina, and with gem traders, diplomats and nongovernmental organizations elsewhere, reveal a dizzyingly corrupt and brutal industry funded almost completely by Chinese trade.

Descriptions of the harsh conditions at the mines were corroborated by rare footage filmed there by a local journalist hired by the New York Times.

The video from inside the checkpoints shows lush rolling hills scarred by craters that descend for hundreds of meters into pits. There, hundreds of men worked in the searing heat, picking through rocks with rudimentary shovels, or their hands, in search of the gem.

In some cases, the miners shoot water from high-powered hoses to break up the rock walls, a dangerous practice that sometimes triggers landslides.

Also visible in the footage: an open-air heroin shooting gallery, hard up against a mine.

Myanmar’s jade industry took off in the 1980s after the introduction of market reforms in China. For the first time since Mao Zedong (毛澤東) began blocking private enterprise in 1949, entrepreneurs betting that the gemstone would become big business in China started jumping into the trade. Their financing helped build an industry that churns out the Buddha figurines and thick bracelets that have become status symbols for China’s middle class.

KACHIN INSURGENCY

The burgeoning market transformed the Kachin insurgency, which started in 1961 as a fight mostly about political independence, into a raging battle that extends to natural resources. A 1994 ceasefire stopped the violence, but gave the Burmese junta and its Chinese backers control over the best tracts in Hpakant.

The ceasefire fell apart in 2011, with jade fueling the conflict by funneling money to both sides. Local news outlets say that about 120,000 people have been displaced by the fighting, which included military airstrikes in Kachin. The death toll remains in dispute.

In an interview, Dau Hka, a senior official with the political wing of the rebel Kachin Independence Army (KIA), described a sophisticated revenue collection system in which mining companies that want to operate in areas under the rebels’ control “donate” money to them, providing half of their operating budget.

“The donations are not exactly legal,” Hka said.

The KIA also makes money by working with Chinese companies to smuggle jade through the jungle into China, according to activists and a Chinese jade importer.

“They will call us beforehand and we will come in a convoy to pick up the goods,” said the trader, who would give only his surname, Chen (陳).

The rebels demand cash on delivery, he added.

Yet the fighters’ spoils pale in comparison to those collected by the powerful Burmese military elite, whose companies receive the choicest tracts of mining land from the government, miners and international rights groups said.

Like the KIA, some Burmese military officers are also involved in smuggling, extracting bribes to allow the illicit practice, activists said.

“The top dogs are the Burmese military,” Davis said.

Perhaps half or more of the jade that is mined vanishes into the black market, industry observers said.

The Burmese Ministry of Mines, in an e-mail response to detailed questions, denied that smuggling is a major problem.

Although official jade sales generate significant tax revenue, David Dapice of Harvard University’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, which did an extensive study of the jade trade, estimated that the government is losing billions of US dollars a year to illegal trading.

However, the possibly greater tragedy is the heroin epidemic ravaging a new generation of Kachin.

HEROIN’S HIGH TOLL

For decades, heroin was rare in the state. The surge in the jade trade changed all that, creating a market for drugs among the thousands of Kachin workers who flocked to the mines seeking an escape from poverty.

However, Ze Hkaung Lazum, 27, said the mines proved to be a trap. Heroin is sold in bamboo huts “like vegetables in a market” for between US$4 and US$8 a hit, he said. Miners squat in the open, next to piles of used needles, with syringes hanging from their arms.

If the drug fails to take the workers’ meager earnings, the prostitutes waiting nearby are happy to oblige for US$6 per 20-minute session. Within months, Ze Hkaung Lazum was a frequent customer of both.

Some miners, like Bum Hkrang, a 24-year-old recovering addict, said they need the drug to steel themselves for the backbreaking and dangerous work their Burmese and Chinese bosses demand; others said they simply fell into addiction because the drug was so available, with some heroin dealers accepting jade as payment.

“Try digging all day with an iron rod and see how you feel,” Bum Hkrang said, adding that he had abandoned his university studies for the promise of fast riches.

Heroin, he discovered, gave him enough energy to work 24 hours straight.

Miners say at least four out of five workers are habitual drug users. Users who overdose are buried near the mines, amid groves of bamboo.

Over time, heroin abuse spilled into the broader population.

Like many locals, Tang Goon, who works on an anti-drug project, believes the Burmese government is distributing heroin to weaken the ethnic insurgency, with the military allowing pushers past their checkpoints.

“Heroin is their weapon,” he said.

However, whether the trade is driven by politics or simple greed, the toll has been devastating.

Kachin activists estimate that a sizeable majority of Kachin youth are addicts; the WHO has said about 30 percent of intravenous drug users in Myitkyina have contracted HIV.

With virtually no funding from a central government focused on other priorities, the Kachin rely on church rehabilitation centers that preach a spiritual, if controversial, solution to addiction.

At one, the Change in Christ center outside Myitkyina, founder Thang Raw runs a treatment program based on rapturous hymnal sessions and baptismal-like dunks in a concrete water tank that are meant to soothe the agony of withdrawal.

The treatment did little to help Mung Hkwang, 21, who despite the sweltering heat lay shivering recently inside the center’s thatch-roofed dormitory. His ankle, tattooed with a marijuana leaf, was shackled to his bed to keep him from running away to feed his habit.

“It ruined my life and destroyed my education,” he said of the drug.

Just weeks later, Mung Hkwang ran away and died from a heroin overdose.

THE HAND OF CHINA

There are plenty of culprits in Myanmar’s illicit jade and drug trades, but many human rights activists reserve their harshest criticism for China, which they say is content to profit from the mounting chaos that has engulfed Myanmar’s jade industry.

“China prioritizes naked greed over any concern for the local population or how the jade is extracted,” said David Mathieson, a senior researcher on Myanmar for Human Rights Watch.

Jade has fired the Chinese imagination for thousands of years. According to legend, the birth of Confucius (孔子) was prophesied by a unicorn who gave his mother a jade tablet heralding his destiny. To this day, many Chinese reportedly believe the stone wards off misfortune and heals the body.

“Jade, from ancient to modern times, is a symbol of grace to Chinese people,” said Zhi Feina, 34, a civil servant and repeat customer at the Beijing Colorful Yunnan Co, an opulent three-story jade emporium in Beijing where she was trying on bracelets.

The state-affiliated Gems and Jewelry Trade Association of China estimates that annual sales of jade are as high as US$5 billion, more than half of which comes from Burmese jade.

In a rare admission, Chinese Ambassador to Myanmar Yang Houlan (楊厚蘭) confirmed that some Chinese are breaking Burmese laws, but he said Beijing was trying to clamp down.

“There are some businesspeople engaged in illegal activities who, attracted by outsize profits, cross the border to mine or smuggle jade,” Yang said in an e-mail, adding that the two nations have stepped up cooperation on border controls and money-laundering investigations. “However, there are some parts of this illicit trade that — like drugs — cannot be stamped out.”

Activists dispute the notion that the governments are serious about cracking down. Without a stronger push for reform from China, they have little hope that conditions will improve, they said.

So far, there does not appear to be an appetite for major change. During an interview, Gems and Jewelry Trade Association of China deputy secretary-general Shi Hongyue (史洪岳) refused to even discuss the ills plaguing the Burmese jade trade.

When pressed about the heroin epidemic at the mines, Shi was dismissive.

“Honestly, the amount of drugs they are using is not really that much,” he said.

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization