The 18cm scar runs diagonally across the left flank of his skinny torso, a glaring reminder of an operation he hoped would save his family from debt, but instead plunged him into shame.

Chhay, 18, sold his kidney for US$3,000 in an illicit deal that saw him whisked from a rickety one-room house on the outskirts of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, to a gleaming hospital in the medical tourism hub of neighboring Thailand.

His shadowy journey, which went unnoticed by authorities two years ago, has instigated Cambodia’s first-ever cases of organ trafficking and the arrests of two alleged brokers.

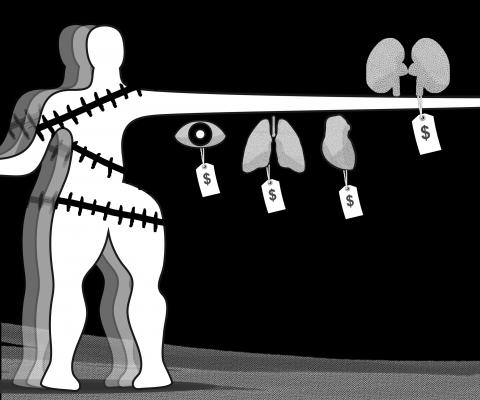

Illustration: June Hsu

It has also raised fears that other victims hide beneath the radar.

At the corrugated-iron shack he shares with nine relatives, Chhay says a neighbor persuaded him and a pair of brothers — all from the marginalized Cham Muslim minority — to sell their kidneys to rich Cambodians on dialysis.

“She said you are poor, you don’t have money, if you sell your kidney you will be able to pay off your debts,” the teenager said, requesting that his real name be withheld.

Identical stories have long been common in the slums of India and Nepal, better-known hotspots for traffickers. Up to 10,000, or 10 percent, of the organs transplanted globally each year are trafficked, according to the latest WHO estimate.

However, on discovering the broker earned US$10,000 for each kidney they sacrificed, the donors filed complaints, alerting police in June to a potential new organ trade route.

“Kidney trafficking is not like other crimes... If the victims don’t speak up, we will never know,” Phnom Penh deputy police chief Prum Sonthor said.

In July his force charged Yem Azisah, 29 — believed to be a cousin of the sibling donors — and her stepfather, known as Phalla, 40, with human trafficking.

The pair are being detained and await trial.

Trafficking is a widespread problem in impoverished Cambodia and police routinely investigate cases linked to the sex trade, forced marriage or slavery — but this was the first related to organs.

“This is easy money that earns a lot of income, so we are worried,” Prum said, adding that there were at least two other Cambodian donors taken to Thailand who had not filed complaints.

The complicity of donors, whether compelled by poverty or coerced by unscrupulous brokers, makes it an under-reported crime which is difficult to expose.

In August media reports emerged about new alleged organ trafficking cases at a military hospital in Phnom Penh.

Prum, who investigated the case, said it was a training exercise between Chinese and Cambodian doctors, using voluntary Vietnamese donors and patients.

However, he was unable to rule out whether money changed hands.

Chhay watches from the sidelines as boys his age play soccer, two years on from an operation that has left him feeling weak, ashamed and still in debt.

“I want to tell others not to have their kidney removed like me... I regret it. I cannot work hard anymore, even walking I feel exhausted,” he said.

In July he started work at a garment factory.

Little research has been done on the impact of transplants on paid donors like Chhay, but the WHO has reported an association with depression and perceived deterioration in health, highlighting the lack of follow-up care.

Chhay remembers few details of a transaction that still haunts him, claiming no knowledge of the Thai city where he was taken or the woman he sold his kidney to.

In Thailand health authorities are trying to shed more light on the murky trade, with several Bangkok hospitals under investigation.

Focus has fallen on the documents traffickers forge to prove donors and recipients are related — a requirement in many countries where it is illegal to sell an organ.

“We’ve asked hospitals to be more careful” when checking documents, Medical Council of Thailand president Somsak Lolekha said, adding that his organization was reviewing its transplant regulations.

Driving the demand for a black market in organs is the globally soaring number of sick patients waiting for transplants, especially kidneys.

In Thailand alone there were 4,321 people on the organ waiting list up until August, with deceased donors’ organs forming about half of the 581 kidneys transplanted last year, according to the Thai Red Cross Organ Donation Centre (ODC).

All over the World this increasing reliance on living donors has left desperate patients scouring for volunteers in their families, or, in some cases, recruiting underground.

Prompted by concerns over trafficking, the ODC, which oversees organ donations, launched a pilot project in April making it compulsory for hospitals to provide them with details of living donors.

“Before they could come to Thailand without our knowledge... We are concerned about hospitals where they are not following rules, that’s why we asked for a register of living donors,” ODC director Visist Dhitavat said.

While regulations are being tightened, experts fear the booming medical tourism industry in Thailand, reputed for high-quality but low-cost care, could give rise to more criminal networks cashing in on the vulnerable.

“It could be the tip of the iceberg,” UN Office on Drugs and Crime representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific Jeremy Douglas said on the recent Cambodian arrests.

“There could be a lot of others [cases] that aren’t just simply coming to trial,” he said.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged