Michiko Yamada, 75, ran barefoot with her husband to the rooftop of a hospital in the coastal town of Rikuzentakata in northeast Japan, barely outracing the tsunami unleashed by Japan’s strongest earthquake. They spent a cold night there, before a helicopter plucked them to safety.

Their neighbor Hayato Murakami, 73, scampered up a hill not far from his home just as the onrushing waters of the gargantuan wave washed over where he had been standing.

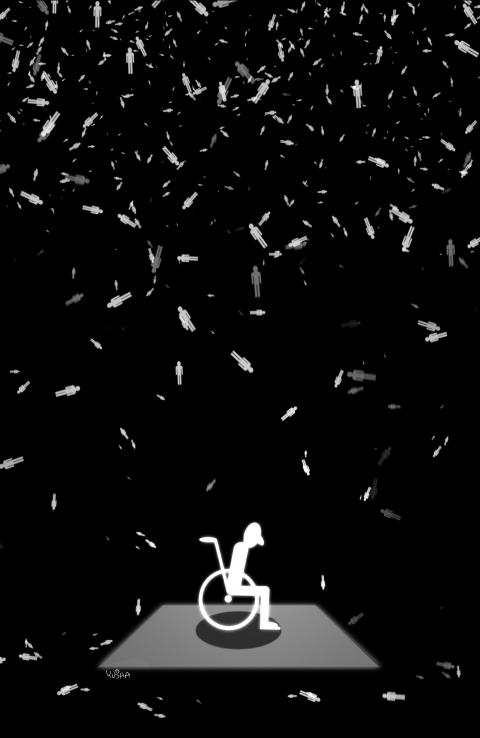

Many elderly people are among the 25,600 dead or missing in Japan’s double disaster, including at least 1,800 people in Rikuzentakata, but many, if not most of the survivors seen huddled on their tatami mats in the town’s temporary shelters, are also old and that is one of the more remarkable features of the astonishing events of March 11.

These elderly survivors, most of them on medication, lame and infirm, drew upon some inner reserve of strength to run up hills and rooftops, scramble atop cars or cling to debris in the swirling tsunami waters to save themselves.

Now a town whose population has been in decline for years, abandoned by many of its young, who have migrated to the big city lights to find work, has gotten even older. Many of those killed here were vitally needed workers. With the city almost totally devastated, more of the young will leave.

“The economy here was not good to begin with and now we have nothing left,” said 35-year-old Tetsuaki Konno, who worked for a local food processor destroyed by the tsunami. “If I have no job, then I am troubled, so I may have to leave. It’s not like I have that much attachment to this city.”

More than a third of Rikuzentakata’s population was 65 and over, compared with nearly a quarter in Japan as a whole, which itself has become the fastest ageing country in the world. What to do with shattered coastal towns such as Rikuzentakata will be one of the key issues of the rebuilding effort and a test of how Japan will handle its ageing challenges.

Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano made that point in an interview on Thursday. The huge national effort needed to overcome what Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan has called Japan’s biggest crisis since the end of World War II could help Japan tackle the deep-rooted problems of a fast-ageing society and an economy facing stiff competition from global rivals.

“The energy needed to overcome the quake disaster and nuclear accident will be overwhelmingly greater than that needed to overcome those sorts of problems,” he said. “In the process, we may take a big first step toward finding out how to resolve such problems as those of an ageing society with a low birthrate. Those who are left will have to rebuild their lives after losing almost everything and doing that could, in a sense, become a model for how to ... create communities and social welfare systems in areas not hit by this disaster.”

Schools and hospitals that have been turned into temporary shelters are full of senior survivors. Almost all of them fled with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and they seem unable to contemplate a problematic future. They remain in a state of stunned disbelief over what happened.

TWO TERRIFYING MINUTES

For two terrifying minutes starting at 2:46pm on March 11, the magnitude 9.0 earthquake shook homes and buildings, rupturing streets in this town of 23,000 people. Many knew a tsunami was bound to come and they began running from their houses.

Rikuzentakata has long been used to tsunamis and conducts annual drills for them. Just last year, a tsunami triggered by Chile’s earthquake caused some damage. The town, which boasts one of the most beautiful beaches in northeast Japan and is touted as having one of the country’s 100 best views, had built high seawalls to thwart tsunamis among the many infrastructure projects Japan had undertaken over the past two decades to lift the economy out of its doldrums.

However, the dark waves the size of a three-story house, which followed the quake 20 minutes later, roared in from Hirota Bay and bulldozed right through the barrier and on through the town until they smacked into the hills several kilometers beyond, atop which the survivors watched in horror.

“There have been tsunamis before, but they were just a little bit,” Yamada said from her new home at a middle school shelter in the ruined town. “The tsunami was black and I saw people on cars and an old couple get swept away right in front of me.”

This area of northeast Japan is mountainous near the coast and the coastline itself largely consists of jagged cliffs and rock pillars dubbed “The Sea Alps.”

Rikuzentakata is the exception. Its long flat beach, lined with tall pine trees and sporting a resort hotel, was the pride of the town — and did nothing to impede the tsunami.

Futoshi Toba, 46, who only became mayor of Rikuzentakata last month, lost his wife to the killer waves. He listens patiently as a steady stream of supplicants come to him with their requests at the temporary city hall he has set up in a school lunch catering center, one of the few buildings left standing.

About 80 of the 230 employees working at City Hall are dead or missing after the tsunami ploughed through the building. A fifth of the fire brigade perished even as they ferried children and the elderly to safety.

“From my point of view, many of them could have held important roles in our city,” the mayor said. “We do not have enough manpower now and the city is not functioning.”

A number of high school students are also among the dead and missing — a younger generation desperately needed to help reverse Rikuzentakata’s long slow decline.

The mayor had plans before all this happened to lure back the young who go to Sendai — the main city in the area — or even Tokyo for university and never come back.

“We used to have a beach,” he shrugged. “In this region, where the coastline is saw-toothed, here the coastline was straight for 2km and pine trees were growing, which is very rare, so many people visited from inland. I wanted to rebuild tourism, as well as the local seafood industry, with the help of many young people, but now the situation is like this.”

Fishing was important, including scallops and abalone. Oyster beds were cultivated in Hirota Bay. The industry, in fact, was just recovering from last year’s tsunami, the mayor said.

“I can’t tell you how many people would want to do this again,” he said.

Construction of temporary housing has already begun in Rikuzentakata. Toba said the townspeople want to stay together and rebuild the town, which is now a vast field of rubble, but it will be many months at least before permanent housing can be built for the displaced and some fear they will be forced to settle elsewhere.

Even before this disaster, the government had begun merging small towns that have been gradually hollowing out for years, though it may come under pressure to keep the disaster-struck ones intact.

“There will be a political and emotional response demanding rebuilding of most of the affected villages, even though it may not make social and economic sense to do so,” said Michael Auslin, a Japan expert at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank.

Like many other towns in Japan, and indeed the national government itself, Rikuzentakata had piled up debt to improve infrastructure, while trying to maintain the same quality of services to its citizens even as its sources of income dwindled. Now the town’s finances have gone from dire to even worse.

“People lost their fixed assets, so we will not receive taxes for that,” the mayor said. “There are no places to work, which means no income tax. We will need the national government to aid us fiscally.”

However, Japan’s debt is already more than double that of its US$5 trillion economy and the rebuilding costs will add a heap more to it.

HUGE COST

The Japanese government estimates the disaster could ultimately cost more than US$300 billion — three times that of the 1995 Kobe earthquake and dwarfing even that of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, making it the world’s costliest natural disaster.

Standard & Poor’s had cut Japan’s credit rating weeks before the quake, saying Tokyo had no plan to deal with its mounting debt. The rating is now one notch below Spain’s.

Japan’s nearly two-decade long economic doldrums had already set in at the time of the Kobe quake, but government debt then stood just above 50 percent of GDP. Only 12 percent of the population was over 65, half what it is today.

Even before the disaster, Tokyo had talked of the need to loosen up immigration to allow foreign workers to fill the growing gaps left by its ageing and declining population. It had also acknowledged a need to reform the highly inefficient, but politically influential farm sector.

Could the disaster spur such changes?

Auslin says no.

“I think just the opposite will happen — a renewed emphasis on tapping Japanese traditional strengths and ‘doing it by ourselves’ (with lots of foreign aid, of course) so as not to leave the impression that the quake wound up breaking the Japanese spirit or permanently altering Japanese culture,” he wrote in an e-mail interview.

A weak Democratic Party of Japan government will be under enormous pressure to deal with the multiple demands of the crisis, including the near meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in the quake zone.

“There will be short-term political unity among the parties, but I expect soon enough there will be finger pointing and accusations among political parties,” Auslin added.

Yukiko and Koji Yamaguchi, a retired couple in their 70s, escaped the tsunami carrying only their puppy Choco with them. They sit next to each other at a temporary shelter in the gymnasium of a Rikuzentakata middle school, she reading a newspaper, he a manga comic.

Posters hung at the entrance to the gym say: “Let’s do our best Takata, let us rejoice that we are alive.”

Like other shelters in the shattered town, it appears to be filled predominantly with the elderly.

The Yamaguchis, who have been married for 48 years, are among the generation that helped rebuild Japan from the ashes of World War II to become the world’s second-biggest economy and an innovative manufacturing leader. They would like to see their town rebuilt, but just don’t see how.

“I’m ready to do as much as I can, but when you’re over 70, you have problems with your eyes and legs,” the wife, Yukiko, said. “I’m worried the town will disappear. I would like to hear the young people say: ‘Don’t worry about it,’ but many of them have died.”

“Old people can’t work and stores may not be able to make a comeback,” she said. “It’s not just one small town, but the entire coast. We can help one another, but there is a limit to that. I can’t commit suicide, so I’ll do my best.”

Her husband, Koji, said he can’t imagine what the future will be like when the couple has nothing at all to their name now.

“I feel that it will somehow work out, that I will somehow make it work out,” he said.

Then he added with a laugh: “My job now is just to sleep.”

SIMPLER TIMES

In simpler times, people inland farmed and coastal residents fished. The northeast once supplied 20 percent of Japan’s rice needs, but farming has become a part-time occupation in many areas and the fishermen have been crowded out by more efficient factory ships.

Data from the farming ministry showed the number of farming households in the northeast fell by 30 percent between 1985 and 2005, and in 2005 nearly a third of the farmers were 65 or over compared with a national average of 17 percent.

The government used to provide younger workers in the area with jobs on public works projects, which also kept the stagnant Japanese economy from tipping into recession, but those programs began drying up years ago as the national fiscal debt mounted.

“Here in the countryside, public works was very necessary,” said Tsuneo Onodera, 71, as he surveyed the ruined town from atop a hill. “Farming is not sufficient to make a living, so people used to work in construction in the summer. Then the public works stopped coming and we started having trouble with our livelihoods.”

That could soon change.

About 130,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed in total in the disaster area, along with roads, bridges, ports and railways. That will require the biggest reconstruction effort Japan has faced since World War II.

As the world’s third-largest construction market, Japan has the resources, skills and social cohesiveness required to rebuild quickly, but the disaster may also spur it to think harder about how — and where — to rebuild devastated towns and villages, experts said.

“It will be a good chance to rebuild new kinds of towns now,” said Akira Yamasaki, an economics professor at Chuo University in Tokyo. “It would not be very convincing to invest in areas where no one will be living in 20 years. So the key to whether these areas could be rebuilt is whether the people there would be prepared to live there in the long-term, produce things there and have children. The entire country is having a tough time deciding whether it should invest in this road, this dam, this port, this airport. [The quake] showed Japan’s bigger problem.”

Japan is filled with towns like Rikuzentakata, falling into slow decline along with Japan’s population. The March 11 catastrophe will only accelerate that trend. By 2050, almost 40 percent of the population will be aged 65 and over, and the overall population by then is projected to dwindle to 95.1 million from a peak of 127 million last year.

Over the next four decades, according to current demographic trends, the economy will start shrinking along with the population, unless productivity somehow outpaces the decline in the labor force. In a milestone of that decline, China at the end of last year passed Japan as the world’s second-biggest economy.

The first members of the post-war baby boomers will start to retire this year and reinforce a demographic downward spiral — increased deficits to fund pensions and healthcare, less revenue from workers’ income, more debt and possibly more deflation.

Rikuzentakata has about 20 nursing homes and facilities, none of which were seriously damaged in the tsunami. With the likelihood that young people will move elsewhere in search of work, the picturesque coastal town could well end up becoming a retirement center — if it continues to exist at all as a town.

Welfare worker Satoshi Yoneta said the displaced people worry they may be moved away from the town.

“They have no idea where they’ll be living. It was perhaps half in jest, but we were talking about maybe inviting the US military to set up a base here,” Yoneta said.

About 20 warships from the US Seventh Fleet have sailed to the disaster zone, along with soldiers and airmen to conduct humanitarian missions, reminiscent of a similar operation in Indonesia during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

The operation has helped smooth ties with Japan that had been frayed over the government’s vacillations over the future of the huge US base on the southern island of Okinawa, but other town residents see no future at all for Rikuzentakata, let alone one as host to a foreign military base in Japan’s heartland.

Takao Sato, 53, a senior member of the volunteer fire brigade, described Rikuzentakata as a community marked for extinction.

“I imagine it will be really tough to rebuild this place,” he said, as he and other firemen searched the rubble for dead bodies and personal effects.

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe (VE) Day, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) made a statement that provoked unprecedented repudiations among the European diplomats in Taipei. Chu said during a KMT Central Standing Committee meeting that what President William Lai (賴清德) has been doing to the opposition is equivalent to what Adolf Hitler did in Nazi Germany, referencing ongoing investigations into the KMT’s alleged forgery of signatures used in recall petitions against Democratic Progressive Party legislators. In response, the German Institute Taipei posted a statement to express its “deep disappointment and concern”