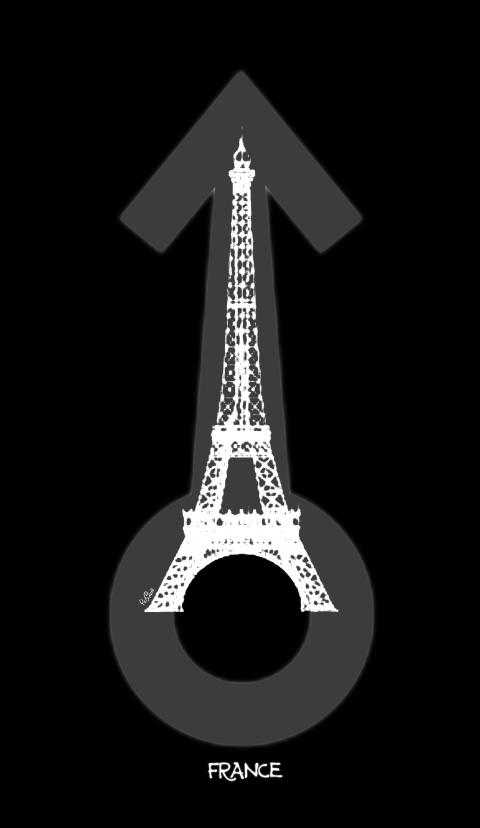

The twin stereotypes about gender in France are wholly contradictory: On the one hand, they have titanic feminist theorists, from social theorist Simone de Beauvoir via feminist writer Helene Cixious to writer Virginie Despentes, a tranche of thinkers so heavyweight that the rest of Europe couldn’t match it if we pooled all our feminists. On the other hand, the mainstream culture looks quite sexist. The women seem bedeviled by standards that are either unattainable (to be a perfect size eight) or demeaning in themselves (to be restrained, demure, moderate in all things, poised; a host of qualities that all mean “quiet”). However, this dichotomy is impossible. Either the feminist intellectuals had no impact or the sexism is a myth.

Elsa Dorlin, associate professor at the Sorbonne, currently a visiting professor in California, dispatches the first quantity pretty swiftly.

“French feminism is a kind of American construction,” she said. “Figures like Helene Cixous are not really recognized in France. In civil society, there is a hugely anti-feminist mentality.”

The standard structural markers of inequality are all in place: The figure proffered for a pay gap is a modest 12 percent, but this is what is known as “pure discrimination,” the difference in wages between a man and a woman in exactly the same job, with the same qualifications. When the Global Pay Gap survey came out at Davos, France came a shocking 46th, way behind comparable economies (Britain is 15th, Germany 13th) and behind less comparable ones (Kazakhstan scored higher).

Female representation in politics is appalling, due to very inflexible rules about the pool from which the political class is drawn. All politicians come from the highly competitive set of graduate schools Les Grandes Ecoles (apart from French President Nicolas Sarkozy) which, until recently, had only a smattering of women, and none at all in Polytechnique (it is sponsored by the Ministry of Defense; women are now allowed in).

When there is a high-profile female face in politics, it is indicative of some force other than equality. At the local elections last week the two big winners were the Socialists, whose leader is Martine Aubry (daughter of former president of the European Commission Jacques Delors), and the National Front, led by Marine Le Pen (daughter of five-time French presidential candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen). So what we’re seeing there is not so much the smashing of the glass ceiling as a freak shortage of sons in a political culture so stitched-up that it’s effectively hereditary.

As for the lived experience of being female, it sounds like hard work, even as described by women who say they love it. Thomasine Jammot, a cross-cultural trainer (who teaches traveling business people how they might overcome cultural misinterpretation, on their own or someone else’s part), said that she does not feel discriminated against, nor objectified.

“There is a permanent ode to women in France,” she said. “We are loved very well.”

However, she added: “There are many things you can’t do, as a woman, in France. You can’t be coarse or vulgar, or drink too much, or smoke in the street. I would never help myself to wine.”

“How would you get more wine?” I asked, baffled.

“At the end of an evening, I might shake my glass at my husband, but no, I would never touch the bottle,” she said.

Sometimes it sounds not so much sexist as so intensely gendered that even men must feel the weight of constraint, of expectation. However, at least they won’t have to do the laundry as well.

Berengere Fievet, 35, is a single mother and student in psychology, as well as a part-time teacher.

“Nothing has changed much in the past 20 years. For men, women are just women: sex objects. Your appearance will change everything, even for an interview for a job. In France you employ anyone you like. -If the -interviewer thinks that you’re too fat or ugly: dommage [damage] for you!” she said.

This is underlined by a bizarre new initiative, Action Relooking, in which a handful of lucky unemployed French women are given a government makeover, in order to look pretty for a job interview.

“Women feel the pressure to maintain their ‘physique’ more in France than anywhere else in Europe,” said Nicole Fievet, 63, a senior council official. “The pressure comes from society itself, not only from men, but women. I am still a bad example to talk about it. I spend my life to look after my garden more than me. As a result, I never found a husband.”

It is against this backdrop — conservatism and rigidity, rather than an all-out war between the sexes — that a bitter struggle has developed which started with a schism between feminists, but extends far beyond.

In 2002 it was made illegal to “passively solicit.” Mainstream feminists — politicians, unionists, various figures who had grouped together in 1996 under the title CNDF — supported the law; as prostitution constituted violence against women it obviously should be outlawed. Activists countered that this denied prostitutes even the patchy safety of a busy street. They said, furthermore, that this was tacit racism, as these prostitutes tended to be from eastern Europe or Africa, and many were deported following the clampdown (even though there was a caveat offering clemency to any woman who named her trafficker; none ever did).

However, underneath the practical injustice, there was a more pressing misogyny.

Nellie, a member of the group Les Tumultueuses (she declines to give her surname in case it damages her position as a school teacher), said: “How do you recognize someone who is ‘passively soliciting?’ By definition, she isn’t doing anything. So you know her because her skirt is too short, or she is wearing fishnets, or she has too much make-up on. When you’re not wearing enough clothing, you’re a prostitute. When you’re wearing too much, you’re a Muslim. That’s where we end up, if we judge people on how they dress.”

Soon enough, that is where the system ended up: In 2004 the ban on the veil came up, on the same grounds, that it represented a violence against women.

Again, establishment feminists put up no opposition as, in the end, it is pretty sexist to have your dress code determined by the sexual paranoia of your menfolk. However, this again had a terrible punitive effect on the women it purported to protect — in this case, girls were denied education if they continued to wear a veil.

“You see here the instrumentalization of the rights of women in the name of the fight against insecurity [terrorism]. I’m a feminist activist. I don’t want to say: ‘Feminism is responsible for this situation,’ but we have to do a critical analysis of internal racism in feminism,” Dorlin said.

There are scenes that cropped up as this legislation was going through that beggar belief: Les Ecoles pour Tous et Tout was a loose collective campaigning for girls who wore the veil not to get kicked out of school. They wanted to join the demonstration on International Women’s Day, but were disallowed until some plan was devised to hide them behind women who weren’t wearing veils. They had the street cleaners coming up behind them, as if they were literally feminism’s dirty secret.

“In 2003 we had huge strikes about pensions, about pay, about conditions, there was so much solidarity. Suddenly, the next year when this ban came in, that was gone. I lost friends, teachers were fighting in the staff room,” Nellie said.

“One teacher said to me: ‘If I can save only one, it’s OK with me if 100 are sent out.’ I was shouting: ‘You’re a teacher! You are here to teach.’ And he said: ‘I repeat it and I mean it,’” Nellie said.

Ann, also from Les Tumulteuses said simply, of the veil: “On the right, they say: ‘That’s Islam coming to France, we’re going to lose our identity.’ On the left, they say: ‘This is against women’s rights,’ but we should be outraged to see a girl be forced out of school. We should all be outraged.”

Next month, a new ban on the niqab, passed last September, will come into force. Would this have happened in a country where it was less routine, less state-sponsored, to judge a woman on her appearance? I think not, but it’s hard to prove.

Note: some names have been changed.

ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY ELODIE GUTIERREZ

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) concludes his fourth visit to China since leaving office, Taiwan finds itself once again trapped in a familiar cycle of political theater. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has criticized Ma’s participation in the Straits Forum as “dancing with Beijing,” while the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) defends it as an act of constitutional diplomacy. Both sides miss a crucial point: The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world. The disagreement reduces Taiwan’s

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is visiting China, where he is addressed in a few ways, but never as a former president. On Sunday, he attended the Straits Forum in Xiamen, not as a former president of Taiwan, but as a former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman. There, he met with Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Chairman Wang Huning (王滬寧). Presumably, Wang at least would have been aware that Ma had once been president, and yet he did not mention that fact, referring to him only as “Mr Ma Ying-jeou.” Perhaps the apparent oversight was not intended to convey a lack of