Abandoned mines in Romania leach waters contaminated by heavy metals into rivers. A Hungarian chemical plant produces more than 90,700 tonnes of toxic substances a year. Soil in eastern Slovakia is contaminated with cancer-producing PCBs.

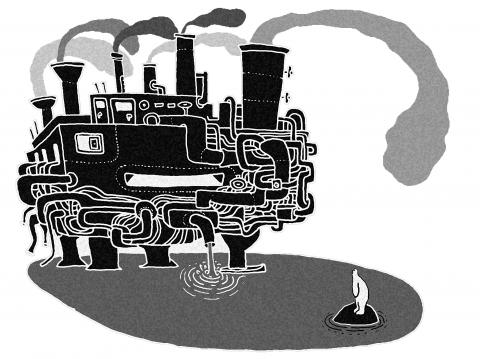

The flood of toxic sludge in Hungary is but one of the ecological horrors that lurk in Eastern Europe 20 years after the collapse of the Iron Curtain, serving as a reminder that the region is dotted with disasters waiting to happen.

Much of Eastern Europe is free of many of its worst environmental sins with the help of Western funds and conditions imposed on Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and the Czech Republic in exchange for membership in the EU.

Still, the sludge has focused attention on less visible dangers that survived various cleanups in the region.

The caustic spill — Hungary’s worst ecological disaster — also has raised questions about whether investors who took over Soviet-era factories from the state 20 years ago are at fault for not spending enough on safety.

Eight people died in the Oct. 4 deluge of red sludge from a 10 hectare storage pool where a byproduct of aluminum production is kept.

Calls for greater cleanup efforts apply not only to Hungary, which considered itself ahead of most of the former Soviet bloc in fixing ecological harm, but also to neighbors like Serbia that hope to join the 27-nation bloc.

“The scary thing is we didn’t know this existed and there could be other ones,” says Andreas Beckmann, director of the WWF Danube-Carpathian program, alluding to the Hungarian spill. “How many other facilities and sites are there that could be a ticking time bomb?”

Environmentalists warn of other potential disasters from seven storage ponds about 100km northwest of Budapest that hold 10.9 million tonnes of sludge accumulated since 1945 — more than 10 times the amount that spilled this week.

“If the gates break there, much of Hungary’s drinking water would be endangered,” WWF official Martin Geiger says.

Other sites — like the Borsodchem plant in northeastern Hungary — pose similar risks to groundwater. That factory churns out 100,000 tonnes of the toxin PVC that contains dioxin, the same poison released into the air by a factory explosion in Seveso, Italy 34 years ago that killed hundreds of animals and turned much of the town into a no man’s land.

Slovakia, Hungary’s northern neighbor, has its own toxic problems, including a huge area in the east of the country that is still contaminated with PCBs from communist times.

Government officials in Bulgaria, alarmed by the Hungarian spill, have ordered safety checks of a dozen waste dams — huge reservoir walls that hold back often heavy metal-laden waste that are prone to leaks or collapse.

In Bulgaria’s most serious such accident, walls at a lead and copper processing factory in Zgorigrad broke in 1966, releasing a flood of sludge that killed 488 people and left much of the immediate area uninhabitable.

Activists say smaller leaks are not uncommon. Ecologist Daniel Popov says toxins leaked into the Topolnitsa River in central Bulgaria last spring when sludge spilled from a storage pond containing waste from copper ore, killing fish.

The inspections are only for operational waste dams, prompting criticism from environmental activists.

Of particular concern, a WWF report says, is a dam near the town of Chiprovtsi in northwestern Bulgaria because it is directly on the Ogosta River, a major Danube tributary.

Hungary’s sludge ponds are a legacy of the Soviet era, when Moscow designated that country as the main producer of alumina, used in the manufacture of aluminum. Reservoirs full of heavy metal-laced sludge are also a threat elsewhere.

A huge storage pond full of corrosive sludge in Romania is part of the landscape of the gritty Danube port of Tulcea. WWF activists say leaks and airborne pollution from the site is responsible for fish and bird deaths nearby.

The Danube — Europe’s second-longest waterway — appears to have escaped immediate harm from the recent Hungarian spill. The same kind of spill at the Tulcea plant would devastate a vast stretch of lakes and marshes at the Danube’s entry into the Black Sea that has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. It hosts more than 300 species of birds and 45 freshwater species of fish.

Memories of an environmental disaster a decade ago in Romania have triggered emergency measures for Tulcea and other suspect sites. That’s when a reservoir burst at a gold mine in the northwestern town of Baia Mare on Jan. 30, 2000, spilling cyanide-laden water into local rivers and killing tons of fish and other wildlife.

Romanian Environment Minister Laszlo Borbely said on Friday that his country was accelerating cleanup plans for 1,000 contaminated sites.

“We must be very cautious now after what happened here in Baia Mare and now in Hungary,” he said.

Romania could access up to 100 million euros (US$138 million) in EU funds to decontaminate polluted sites, he said.

Some of Eastern Europe’s worst environmental horrors were in Romania — among them Copsa Mica, where TV images of black toxic soot from chimneys of a rubber-dye factory falling onto houses, fields, grazing sheep and townspeople shocked the world in 1989.

International outrage contributed to the plant’s 1993 closure.

But “historic pollution” with heavy metals from the 40 years that it operated continues to foul the air. Life expectancy in the area is nine years lower than the national average of 72.

In East Europe, the Danube is shared by seven countries, and it has been the victim of toxic spills even before Hungary’s caustic red muck.

Among the worst incidents came 11 years ago during NATO’s bombing of Serbia, when warplanes targeted fertilizer and vinyl chloride manufacturing plants and an oil refinery in the town of Pancevo, near Belgrade, releasing mercury, dioxins and other deadly compounds into the river.

Foreign funding after the war allowed authorities to contain some of the leaks, but sporadic emissions of toxic gases continue to drive air pollution above accepted levels.

Also near Belgrade, an open pit in Obrenovac just 100m from the Sava — a Danube tributary — contains millions of tonnes of coal ash from the Nikola Tesla Coal Power Plant. The air has unhealthy levels of carbon black, also known as lampblack, for as much as a third of the year. Sprinklers to prevent the ash from becoming airborne are of limited effectiveness on windy days.

Croatia lists nine locations where dangerous waste has been deposited for decades that still need to be cleaned, said Toni Vidan of the group Green Action.

In Vranjic near Split, a factory producing asbestos closed several years ago, but the waste — about 7,000m3 of material mixed with asbestos — hasn’t been completely cleaned up. Two years ago, the presence of asbestos in Vranjic was three times greater than allowed. Even today, residents say particles of asbestos are in the air when the wind blows.

Additional reporting by Veselin Toshkov, Dusan Stojanovic, Snjezana Vukic, Karel Janicek and Alina Wolfe Murray.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

As the highest elected official in the nation’s capital, Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) is the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) candidate-in-waiting for a presidential bid. With the exception of Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕), Chiang is the most likely KMT figure to take over the mantle of the party leadership. All the other usual suspects, from Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) to New Taipei City Mayor Hou You-yi (侯友宜) to KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) have already been rejected at the ballot box. Given such high expectations, Chiang should be demonstrating resolve, calm-headedness and political wisdom in how he faces tough