European leaders led by German Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany and French President Nicolas Sarkozy will act swiftly to make the EU’s reform charter a reality after Ireland’s “yes” vote, despite the lone resistance of Czech President Vaclav Klaus.

The strong endorsement of the Lisbon treaty by the Irish, after eight years of divisive attempts to rewrite the EU’s rule book, has sparked the jockeying for position over the plum jobs that it creates, with former British prime minister Tony Blair now a clear favorite to become the first permanent EU president.

The posts of president of the council and that of a new foreign policy chief with enhanced powers are among the biggest changes under the treaty. But the appointments will not be made in isolation. Who gets what will be intricately linked to the share-out of portfolios in the new European Commission, which will be strongly debated in the coming weeks.

“In the end, it will be one large package which attempts to give every member state something to boast about,” an EU official said.

Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt, the current EU president, is already canvassing names behind the scenes, trying to engineer a consensus on who should fill the two top posts.

Blair’s interest in becoming president has been Europe’s worst-kept secret for more than a year. One of the great ironies of Lisbon is that it was born at a time when European leaders were vowing — following the collapse of its predecessor, the Constitutional Treaty — to create a Europe “closer to the people.”

Yet its first official, permanent president of the council will be chosen in the least democratic of ways — behind closed doors by the 27 EU heads of state and government and without any of the candidates having campaigned before the court of public opinion.

“If you come out campaigning and saying you want it, that could be seen by heads of government as stepping out of line,” said a UK insider. “They see it as their call. A campaign would give your opponents an opportunity to mount their own campaign against you.”

So Blair has been running a non-campaign campaign for months. He has not said he wants the job, but neither has he said he does not. Friends have discreetly sounded out opinion on the diplomatic circuit on his behalf. Having reported back their qualified enthusiasm, he has allowed his hat to enter the ring without actively lobbing it in.

POLE POSITION

Headlines last week saying that Blair was in pole position to become president have been treated with suspicion by some British Labour MPs who want him to get the job, as well as by some commentators.

They believe they are part of a spoiling operation by a Murdoch press that is moving ever closer to David Cameron, leader of the British opposition Conservative party, and that such stories are a way to stir up opposition to the Blair candidacy.

However, the reality is that close supporters of Blair genuinely believe that he is, as one very senior figure put it, “pretty well-placed” and are now prepared to advance his case more actively. They know that few important decisions are reached in the EU, even in an expanded community of 27 member states, without a French-German seal of approval.

And British officials now feel that, following her re-election Merkel can afford to enthuse about a president Blair. During her election campaign it was difficult for Merkel to hint in any way that the former British prime minister might be the best candidate. There is still deep resentment among Germany’s political classes and its public at Blair’s support for the Iraq war, and he is seen as having failed to stamp his pro-European mark on UK policy when prime minister.

The UK’s position outside the eurozone does him no favors either in a country in which the onward march of integration is seen as a moral, as well as a political, imperative.

But with Merkel’s position reinforced, Blair’s supporters are confident, having taken soundings, that she will now team up with Sarkozy, the first European leader to suggest Blair would be good for the job.

One British government source said that France and Germany probably would unite behind Blair for the simple reason that he is such a “big name” and “would make Europe matter.”

With German-US relations on the mend since the election of US President Barack Obama, Blair’s trans-Atlantic enthusiasms, his environmental interests and Middle Eastern contacts would all be key assets in the task of punching Europe’s weight across the globe.

Reinfeldt wants nominations for the two jobs by the end of the month when an EU summit in Brussels should decide on a consensus. There are even calls in Brussels for a meeting of EU leaders sooner, but this appears unlikely.

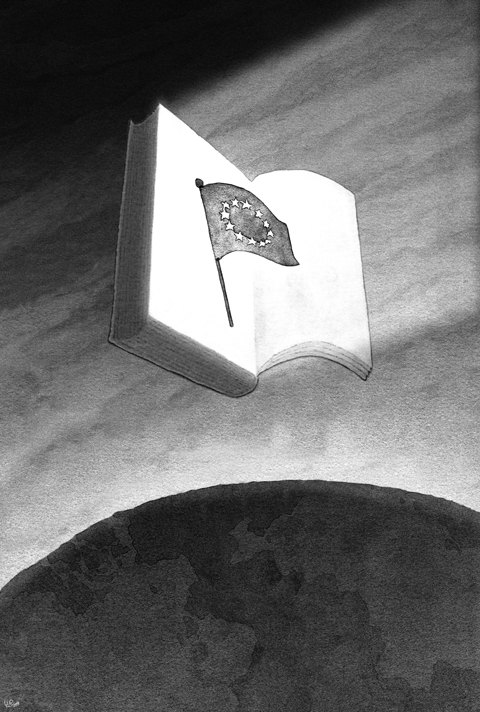

The job description is a blank page. It must go to a former or serving head of government or state in Europe and he or she will chair summits of European leaders. Strangely, what else he or she does is unclear.

Senior diplomats say it will be up to whoever gets the job to shape it. Seldom has such a prestigious and influential position been established with the detail, role, and powers left so vague.

Whoever is installed, there will be frictions with Jose Manuel Barroso, the European Commission president, who has just obtained a second five-year term, and with the leaders of the various countries at the helm of the six-monthly rotating EU presidency.

Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero is next in line for the commission presidency in January and is not keen on being overshadowed by a president Blair.

Reinfeldt is also known to have his reservations about Blair, worried that the interests of the EU’s smaller countries will receive short shrift if the new president comes from one of the EU’s big four — Germany, France, Britain and Italy.

Other names in the frame are Jan-Peter Balkenende, the Christian democrat Dutch prime minister, Paavo Lipponen, the former Finnish premier, a social democrat, Felipe Gonzalez, the center-left former Spanish prime minister and Jean-Claude Juncker, the veteran Luxembourg prime minister, a conservative.

The horse trading is complex, needing to marry jobs with candidates from north and south, big and small countries, the center-right and the center-left.

More immediately, all eyes in Brussels, Berlin, and Paris have shifted from Dublin to Prague where Klaus now stands alone between the Irish referendum and getting the treaty up and running.

He relishes the attention. He is the most Euroskeptic leader in office in the EU. He argues that Brussels is the new Moscow, the EU a successor to the Soviet Union. He insists he will not sign off on a Lisbon treaty, which has already been ratified by the Czech parliament.

Sarkozy is fuming; Merkel is trying not to show her impatience. The only leader in Europe supporting Klaus is David Cameron, who would have to stage a British referendum and kill the treaty if he entered government next year with the Czech president still blocking.

ELECTORAL CLOCK

It is unlikely to come to that, although Lisbon’s fate could still turn into a race against the British electoral clock. Klaus’ allies in the Czech upper house have just deposited a complaint about the treaty in the constitutional court. The Czech government assured EU officials on Friday that it was aiming to get the court to rule quickly, within a matter of weeks, and pleaded with the big pro-Lisbon camp not to put pressure on the Czechs. Was Sarkozy listening?

But Klaus is highly unpredictable, a loner, and nearing the end of his career with little to lose. He thinks he is on a mission to save European democracy and the nation state.

Meanwhile, Blair is said by some to have had some reservations about the presidency post, chief among them that he would earn less money than he does now giving speeches and other private work, and that the job would involve a lot of bureaucratic grind. But he would still earn about £250,000 (US$398,000) a year with generous EU tax allowances, have a staff of at least 20 and a splendid Brussels residence. The post would be for an initial two-and-a-half years, renewable once.

It would place him back not just at the heart of European politics but in the middle of intriguing battles involving British prime ministers past and present if, as now looks highly likely, Cameron gains office committed to wresting back power from the EU.

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

Taiwan People’s Party Legislator-at-large Liu Shu-pin (劉書彬) asked Premier Cho Jung-tai (卓榮泰) a question on Tuesday last week about President William Lai’s (賴清德) decision in March to officially define the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as a foreign hostile force. Liu objected to Lai’s decision on two grounds. First, procedurally, suggesting that Lai did not have the right to unilaterally make that decision, and that Cho should have consulted with the Executive Yuan before he endorsed it. Second, Liu objected over national security concerns, saying that the CCP and Chinese President Xi