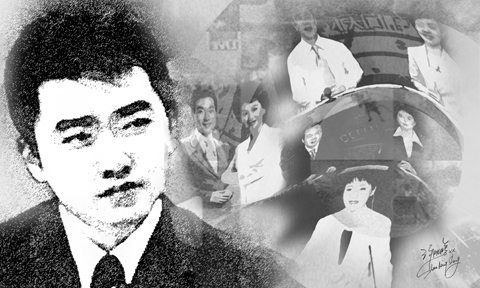

At just 31 years old, Rui Chenggang (芮成鋼) has emerged as the media face of Chinese capitalism — young, smart and, to the dismay of some, deeply nationalistic.

His nightly financial news program attracts 13 million viewers on China Central Television, the nation’s biggest state-run network, where Rui puts tough questions to Wall Street chiefs and Chinese economists, while also delivering a dose of optimism about China’s outlook.

He also writes a popular blog (blog.sina.com.cn/ruichenggang) infused with patriotic rhetoric and he recently published a book, Life Begins at 30, in which he reflects on China’s economic miracle and what he sees as the difficult path ahead.

In a foreword to the book, the president of Yale, Richard Levin, calls Rui “an energetic young standard-bearer of the New China.”

Some critics are less generous, calling him a tireless self-promoter and a propaganda tool of the Communist Party. But Rui, who drives a Jaguar to work and wears Zegna suits, says his goals reach beyond media stardom. He wants to use his celebrity to build bridges with the West and help change world opinion about China, which he says suffers because of biased foreign media coverage and the country’s poor training in communication.

“China has a really bad image problem,” Rui said after a broadcast one evening, while relaxing at the Ritz-Carlton hotel. “I’m gathering a group of people and we hope to do something about that.”

Supporters say Rui’s growing influence among young people is a reflection of China’s development in the 20 years since the government cracked down on pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square.

But his efforts fit the Chinese government’s goal of using state-controlled media to improve the nation’s image abroad, particularly after last year’s Olympic torch relay was marred by overseas protests.

Beijing is pushing its big media properties, all of which are heavily censored and operate under the government’s propaganda department, to expand overseas operations. Under one proposal, China may even create a 24-hour English language news channel to compete with CNN and the BBC, and deliver a more positive view of China’s rise.

Rui Chenggang would appear to be the very model for such national image building.

BIG NAMES

In late January, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, China’s dashing young journalist lined up interviews with some of the biggest names at the event — Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, Craig Barrett of Intel and Stephen Schwarzman of the Blackstone Group. He trades e-mail messages with Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and three times a year he meets “Henry,” as in Henry Kissinger, he said.

He also said he has vacationed with Chinese policy advisers and moderated programs for China’s top leaders, including President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤).

His tone on the air is serious and scripted. Off the air, he sounds like an investment banker who is running for office. He quotes Lao Tzu (老子), makes references to Homer’s Odyssey, explains the pitfalls of private equity and analyzes China’s place in the global financial crisis.

“In China, we have neither a financial crisis nor an economic crisis,” Rui said. “China is going through a serious slowdown. The world is going through a synchronized recession. As a journalist we shouldn’t exaggerate.”

Fluent in English, trained as a diplomat and well-versed in global finance, Rui often sounds like an activist or cultural critic, pressing readers of his blog and book to value traditional culture and even buy Chinese-made goods.

In 2007, his blog ignited a grass-roots movement that helped push Starbucks out of Beijing’s historic Forbidden City. (Rui considered it inappropriate to have a US brand there. Now Chinese tea is served.)

Not everyone likes his personal campaigns.

“As a TV host, I think he’s not bad,” says Zhan Jiang (展江), a journalism professor at the China Youth University of Political Science in Beijing. “But off the show, he’s a bit disgusting. If you protest Starbucks in the Imperial Palace, why don’t you protest speaking English to your Chinese buddy in China? It’s ultranationalism and too narrow-minded.”

Over the years, Rui said, he has formulated his own thinking on China’s affairs. While he calls “blind nationalism” a grave danger to China’s development, he worries more about how the foreign media and Westerners misunderstand his country. The People’s Republic of China, he said, is a mere 60 years old, as young as former US president Bill Clinton.

“We’re a toddler and the US is middle-aged,” he said. “We’re young and dynamic, and we have a lot of growing pains. That’s the way you should look at China. Compare China to the US horizontally and we’re behind, but compare us vertically and we’re making progress.”

AFFLUENT

Rui was born in 1977 and his progress mimics that of China in the last 20 years, when a generation of frustrated, angry, yet idealistic youths from the 1980s gave way to a more affluent generation born after the government began its one-child policy.

“In the 1980s, China was going from a process of being closed to being opened and there was so much uncertainty,” said Yang Xiong (楊雄), a professor of youth studies at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. “Today, things are quite different. Young people have a lot of opportunities.”

Rui grew up in Anhui Province, the son of a writer and a dancer. His father was educated at one of the top schools in Beijing and is the author of a 1974 novel, The Newcomer Xiaoshizhu, which became a best seller that was later made into an animated movie.

As a child, Rui said, he was bilingual and bi-cultural. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday his father read Tang Dynasty poems to him in Chinese. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, he listened to Shakespeare and Tolstoy in English.

He studied at the Foreign Affairs University in Beijing, intending to become a diplomat. But everything changed, he said, after he met Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the former UN secretary-general, during a visit to his school in the late 1990s.

Rui recalled asking Boutros-Ghali which nation he might select if there were a sixth member of the UN Security Council. He said Boutros-Ghali answered “CNN,” saying its influence was bigger than most countries.

And so after graduating in 1999, he took a job at China Central Television and quickly rose through the ranks, helping establish the network’s first English language channel and serving as a reporter and anchor for BizChina, a nightly business news program.

The show gave him access to powerful guests visiting Beijing and helped him win respect overseas. He recently moved to one of CCTV’s Chinese language channels, which is allowing him to broaden his reach and popularity inside China, since his English language channel work was mostly aimed at overseas viewers.

Guo Zhenxi (郭振璽), the president of CCTV’s Channel 2, says Rui is already making a big difference by helping upgrade financial news coverage during the global crisis, drawing as many as 28 million viewers on a single day.

“He’s our star anchor,” Guo said. “For the first time, we’re examining the health of the nation with a television program.”

Because his positions often parrot Beijing’s critiques of foreign journalists, Rui was asked whether he engages in propaganda handed down by the government. He compared it with Fox News coverage of the White House during a Republican administration.

“I hate the word ‘propaganda,’” he said.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they