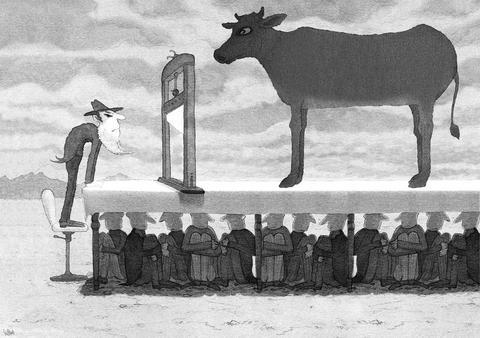

We are playing Russian roulette with the American food supply," thundered Wayne Pacelle.

It was two weeks ago, and Pacelle, president of the Humane Society of the US, was testifying before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Agriculture. The hearing was the culmination of an incredible month for the Humane Society.

On Jan. 30, the animal-rights organization had released a graphic and sickening video of so-called downer cows being horribly abused at a slaughterhouse in Chico, California -- leaking the video first to the Washington Post to reap the maximum publicity and then posting it on its Web site.

The video, showing weak, emaciated cows being manhandled with fork lifts and repeatedly shocked, among other things, had been made by a Humane Society investigator who had infiltrated the plant. He shot the footage over a six-week period last October and November.

The outcry was instantaneous. The Westland/Hallmark plant, where the abuse had taken place, immediately shut down, and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) began an investigation. Two weeks later, the Food Safety and Inspection Service, a division of the agriculture department, forced the company to recall an astonishing 65 million kilograms of meat, saying that its investigation had uncovered rules violations that made the meat "unfit for human consumption."

It was the largest beef recall in US history.

At the hearing, Secretary of Agriculture Edward Schafer -- in the job for barely a month -- was castigated for his department's failure to catch the abuse, while the Humane Society was praised for having brought the abuse to light. But what really drove the hearing was not so much the abuse itself, awful though it was, but the very real possibility that meat from downer cows slaughtered by Westland/Hallmark had entered the food supply.

You see, downer cows -- animals that are not standing on their feet when they are slaughtered -- are said to have an increased risk of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), the dreaded mad cow disease.

skepticism

Although Schafer repeatedly insisted that "this is not a food safety issue," his stance was met with skepticism from many committee members.

"We don't know if these animals presented on this videotape were sick or not," Democratic Senator Tom Harkin said. "We can't keep saying things we don't know."

"We cannot allow a single downer cow into the food system under any circumstances," said Democratic Senator Herb Kohl, the subcommittee chairman.

A number of senators railed about Westland/Hallmark as a supplier of meat to the national school lunch program -- thus potentially endangering children.

And then there was Pacelle, who played the contaminated-food-supply card for all it was worth.

"Downer cows are getting into the food supply," he insisted -- and in his written testimony, he listed potential health hazards that went well beyond mad cow disease.

"Children and the elderly are more likely to fall victim to severe illness," etc, he wrote.

Are you catching a note of skepticism in my tone? You should be. Pacelle and his friends on the Senate subcommittee are right about one thing -- there are indeed downer cows getting into the food supply. Not many, but some. But it turns out that it is perfectly legal -- so long as the cows have been inspected by the government before they are slaughtered. That's the practice Pacelle -- and Kohl -- wants to stop.

But in allowing this practice, is the government really playing Russian roulette with our food? Hardly. It is Pacelle who is playing Russian roulette with the truth.

Mad cow disease is an awful way to die. Contracting it is a little like coming down with Alzheimer's, with the body and brain both deteriorating -- except that it affects people of any age, not just the elderly. It is terrifying even to think about.

It is also, however, quite rare. The world first discovered it in the early 1980s, when there was an outbreak of BSE in humans in England, causing, so far, more than 150 of those horrible deaths. (There is a long incubation period.) But that outbreak also caused scientists to identify the disease and understand what had caused it.

What they learned was that BSE resided in the brains and spinal cords of infected cattle -- and it is generally thought that humans who contract it have somehow ingested that part of the cow.

William Hueston, a public health scientist at the University of Minnesota, has said that the outbreak in England was because of a new kind of machinery that, in separating meat from the carcass of a cow, mixed spinal cords in with other parts of the cow.

Governments all over the world quickly took note and began instituting a series of measures to ensure that BSE-infected cows would not infiltrate the food supply. The US, for instance, ordered stepped up inspections to root out BSE, instituted import controls and mandated rules to ensure that cattle brains and spinal cords did not wind up being ingested by cows as part of their feed.

"The challenge to controlling BSE is to control the feed," Hueston said.

Indeed, he says many scientists believe that even infected cows can be safely eaten so long as their brains and spinal cord have been removed. But as a matter of course, those parts are removed from every cow and on the very rare occasion when a cow is diagnosed with BSE, it is destroyed. In truth, the story of mad cow disease has been a public health triumph.

smaller risk

As for downer cows, in the scheme of things they pose a far smaller risk factor for mad cow disease than, say, cattle feed. Still, the government does not want to take any chances, so its rules state that cattle arriving at the slaughterhouse in a "nonambulatory" fashion must be euthanized and the meat must not enter the food supply.

There is, however, one exception -- an exception that drives Pacelle crazy. If a cow arrives at the slaughterhouse on its feet, passes inspection and then goes down, it can be still be slaughtered -- so long as a USDA veterinarian reinspects the animal.

The chances of such an animal harboring BSE are infinitesimal.

Nonetheless the recall was the result of Westland/Hallmark's failure to call for a second inspection on some occasions. (It is unclear, however, whether any of the cows actually shown in the Humane Society video fit this category.)

The government's position is that the company violated the rules and thus needed to be punished. Recalls are the USDA's primary means of punishing companies.

And yet, what good has the recall really done -- except to scare people into thinking the food supply has been tarnished? Much of the meat that came from the plant has already been eaten. Millions of kilograms of perfectly good hamburger is being destroyed, costing companies that bought meat from the slaughterhouse millions of dollars. Products that contain minute traces of the meat are also being recalled.

When I spoke to Richard Raymond, the agriculture department's undersecretary for food safety, he did not try to excuse the failure of the inspectors to catch the abuse and he vowed to put in place systems that would prevent it from ever happening again.

"We know we have to do better," he said. "We are embarrassed on our watch."

That is all to the good, but renewed enforcement by the USDA surely would have happened even without the gigantic waste of food that the recall represented. The abuse itself is a violation of the law.

As for Pacelle, it is clear that his primary focus is the animal abuse -- and that the bogus food supply issue was merely his hook for the news media and Congress.

Or at least, let's hope he understands that. For if he really believes those downer cows can harm humans, then his actions begin to seem extremely irresponsible.

Consider again the time frame -- the Humane Society investigator began shooting film in early October. If what he saw was really a danger to the food supply, did not he and Pacelle have a responsibility to bring it to the federal government immediately? Instead, the undercover investigator stayed on site for six more weeks. Even then, the federal government did not learn of the video until it was leaked to the Post at the end of January -- nearly two months later.

Pacelle claims that the San Bernadino district attorney's office -- to which he gave the tapes in late November, so that it could prosecute the abuse -- asked him not to show the video to the USDA until it had completed its investigation. But I read several news articles quoting San Bernadino officials contradicting that account.

When I called the district attorney's office, I was told that the two people who could respond to my questions were both on vacation.

And even if that were true, why did he release the video to the Washington Post -- well in advance of the completion of the district attorney's investigation?

Well, you know the answer to that one -- he just could not stand the thought of one more day passing without making a big splash.

When I spoke to him, Pacelle was dismissive of the industry's claim that this was a one-time situation involving a rogue slaughterhouse.

"This was the No. 2 supplier to the school lunch program," he said. "How can they offer us assurance? I am tired of false assurances. We just don't know how widespread it is."

This, too, however, is a gross exaggeration. In truth, most slaughterhouses do not operate the way Westland/Hallmark did. They do not because the law forbids it, but also because it is a terrible business practice. Since the late 1990s, companies like McDonald's and Wal-Mart have had their own auditing programs for slaughterhouses and meat processors -- programs that are in some ways tougher than the USDA's rules. Slaughterhouses can not afford to fail those audits.

Really, when you get down to it, what happened at Westland/Hallmark was a horrible, anomalous case of animal abuse. The company deserves to be out of business and the perpetrators should be prosecuted, as now appears likely. The Humane Society did a good thing in bringing the abuse to public light. But it had nothing to do with the food supply or mad cow disease.

When I asked Hueston what he thought about the way the Humane Society and the body politic had used a food supply scare to heighten what was really an animal abuse problem, he laughed.

"How is that different from anything else in politics?" he said.

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they