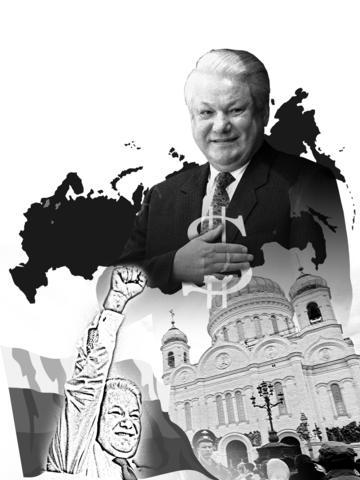

Former Russian president Boris Yeltsin was utterly unique. As the country's first democratically elected leader, he was the first to give up power voluntarily, and constitutionally, to a successor.

However, he was also profoundly characteristic of Russian leaders. Using various mixtures of charisma, statecraft and terror, Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, Alexander II, Peter Stolypin (the last tsar's prime minister), Lenin and Stalin all sought to make Russia not only a great military power, but also an economic and cultural equal of the West.

Yeltsin aimed for the same goals, but he stands out from them because he understood that empire was incompatible with democracy, and so was willing to abandon the Soviet Union in order to try to build a democratic order at home.

At the height of Yeltsin's career, many Russians identified with his bluntness, impulsiveness, sensitivity to personal slight and even with his weakness for alcohol.

And yet in the final years of his rule, his reputation plunged. It was only in the last few months of his second presidential term, after he launched the second war in Chechnya in September 1999, that he and his lieutenants regained some legitimacy in the eyes of the Russian public. Nevertheless, the war caused revulsion among any remaining Western admirers.

Despite his caprices, however, Yeltsin kept Russia on a course of broad strategic co-operation with the US and its allies. Although he opposed the US' use of force against Iraq and Serbia in the 1990s, his government never formally abandoned the sanctions regime against either country. Moreover, no nuclear weapons were unleashed, deliberately or accidentally, and no full-scale war of the kind that ravaged post-communist Yugoslavia broke out between Russia and any of its neighbors, although several of them were locked in internal or regional conflict in which Russia's hand was visible.

The tasks that faced Yeltsin when he attained power in 1991 were monumental. At several crucial moments, he established himself as the only person who could rise to the challenges of transforming Russia from a dictatorship into a democracy, from a planned economy into a free market, and from an empire into a medium-ranked power.

In 1992, as the emerging Russian Federation teetered on the brink of economic and monetary collapse, he opted for radical reform, prompting a backlash from vested interest groups. In the years that followed, he would tilt toward liberal economics whenever he felt powerful enough to do so.

Yeltsin was quintessentially a product of the Soviet system, which made his turn to democracy and the free market, though imperfect, even more miraculous. The son of a poor building worker, he had a meteoric rise through Communist ranks to become party boss in the industrial city of Sverdlovsk, which is now known as Yekaterinburg, in the Urals.

Unlike most other party leaders, he was good at talking to ordinary people, a skill that helped him win support and then power, but he also showed no sign of questioning the Marxist-Leninist gobbledygook that he was required to recite at public events.

It was only after Mikhail Gorbachev, the former general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, summoned Yeltsin to Moscow in 1985 that Yeltsin began to differentiate himself from dozens of other senior party apparatchiks.

Sensing the bitter frustration of Moscow's middle class-in-waiting, Yeltsin quickly gained a reputation as a harsh, if not always coherent, critic of the party's old guard.

Campaigners for democracy admired Yeltsin's struggle against the conservatives in the politburo -- especially after he was forced out of the party's inner circle in November 1987. Determined to outbid Gorbachev as a reformer, he persuaded liberals to overcome their distrust of his provincial manners. They gave him lessons in democratic theory, while he gave them tactical advice.

As the Soviet Union steadily disintegrated, with virtually all of its 15 republics straining at the leash, Yeltsin gained the leadership of the largest -- the Russian Federation -- which placed him in a tactical alliance with independence campaigners in Ukraine, the Baltic states and Georgia.

By June 1991, after quashing a series of challenges to his leadership, he became the first elected president of Russia; two months later, real power fell into his hands, after the failed putsch against Gorbachev of August 1991 by conservatives seeking to prevent the Soviet Union's disintegration. For most Westerners and many Russians, his finest hour came on August 19th that year, when he stood on a tank outside the Russian parliament and defied the hardliners who had seized power.

But Yeltsin himself never succeeded in fully throwing off the intellectual shackles of the past. As president, he talked of economic performance as if it could be improved by decree. Like most Russians, he wanted the material advantages of capitalism, but had little respect or understanding for the rule of law and dispersion of power that makes capitalist institutions work.

Nevertheless, for most of his presidency, Yeltsin kept alive -- albeit with many tactical retreats -- the goal of economic reform. At some level, he sensed that Russia's potential could be unleashed only if the government either faced down, or bought off, the special interests -- military, industrial, and agricultural -- that stood in the way. The economic orthodoxy pursued after the collapse of 1998 laid the groundwork for today's sustained Russian boom.

Yeltsin's tragedy, and Russia's, was that when the country needed a leader with vision and determination, it found an agile political operator instead. By not permitting Russia to disintegrate into anarchy or leading it back to authoritarianism, Yeltsin kept the way open for such a leader to one day emerge.

Unfortunately, his handpicked successor, Russian President Vladimir Putin, has not turned out to be that man, as he has only perpetuated the vicious cycles of Russian history.

Nina Khrushcheva teaches international affairs at the New School in New York City. Copyright: Project Syndicate

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they