For centuries, men have ascended to Japan's imperial throne, one of the world's oldest hereditary monarchies. Eight women have reigned as empresses but never bore heirs, so the Chrysanthemum Throne reverted to a male relative who was a direct descendant of the imperial line.

But faced with the harsh reality that neither of the current emperor's two sons is likely to produce a male heir, a government panel recommended recently that the US-imposed Imperial Household Law of 1947 be revised to allow a female line to hold the throne.

The possibility has ignited a furious debate over the most delicate of subjects -- the imperial system and its significance to Japan -- and over topics as varied as the status of Japanese women, the merits of the concubine system and the purity of the imperial Y chromosome.

"We discussed how to preserve the imperial system from a mid- to long-term point of view," Itsuo Sonobe, deputy chairman of the 10-member government panel and a former Supreme Court justice, said in an interview. "The three major pillars of discussion were that the succession system should be constitutional and stable, and that, furthermore, it should win the people's support."

The panel proposed that an emperor's first child, regardless of its sex, ascend to the throne and, further, that women be allowed to retain their imperial status after marriage. Today, they leave the imperial palace and become commoners when they wed, as Princess Sayako, the daughter of Emperor Akihito, did recently.

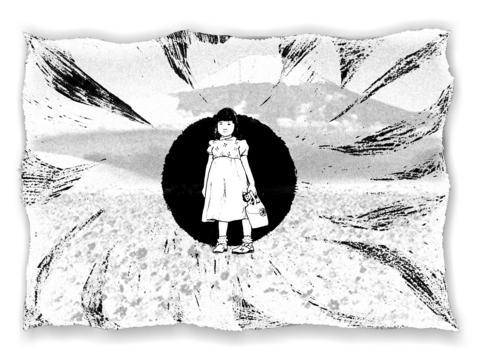

The recommendation, which is expected to be introduced as a bill in Parliament next year, would clear the way for Princess Aiko, the emperor's four-year-old granddaughter, to one day ascend to the throne and have her own firstborn succeed her.

The proposal arose out of the current imperial family situation. Princess Aiko is the only child of Crown Prince Naruhito, 45, and Crown Princess Masako, 42. Princess Masako, a former diplomat educated at Harvard and Oxford, came under intense pressure to bear a male heir since marrying the future emperor in 1993.

Princess Masako gave birth to Princess Aiko in 2001, after which the pressure to have a boy only increased. That is believed to have caused what the Imperial Household Agency said last year was the princess' depression and anxiety. The princess, who has received therapy, has rarely been seen in public since the end of 2003.

Under the current system, a son from Emperor Akihito's other son, Prince Akishino, 40, could ascend. But Prince Akishino and his wife, Princess Kiko, have two daughters, and, despite prodding from the Imperial Household Agency, are not thought to be trying for a third child.

Recent opinion polls show that most Japanese overwhelmingly back the idea of an empress, though support dips for a female line.

According to Japanese myth, the first emperor, Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, began his reign 2,665 years ago; historians, though, trace the start of Japan's imperial system to the fourth or fifth century.

Some opponents of establishing a female imperial line cite that ancient precedent. Tsuneyasu Takeda, 30, a member of a former imperial family branch, said Japan should no more alter Horyu Temple, its oldest wooden building, than interfere with the throne's unbroken male bloodline.

"Why not rebuild Horyu Temple as a concrete building?" said Takeda, author of The Truth About the Imperial Family. "If you did, it would be something completely different."

The emperor, Takeda said, was valued "not because he is intelligent or handsome."

"It's because he is the inheritor of the blood that has been preserved for 2,000 years," he said.

Other opponents add genetics to their argument. Since women have two X chromosomes while men have an X and a Y, the imperial throne's male line has preserved its Y chromosome intact.

"Maintaining the male line is the condition to preserving that Y chromosome," said Hakubun Shimomura, a lawmaker for the governing Liberal Democratic Party, who is one of the leaders of a campaign to reject the panel's recommendation.

"The bloodline is important for the emperor to be a symbol of the nation and the unity of the people," Shimomura added. "This symbolic imperial throne preserves Japan's culture and tradition in total. The imperial throne is Japan itself."

Like many other opponents, Shimomura does not oppose Princess Aiko's ascension to the throne, as long as a male with the right Y chromosome will succeed her. Princess Aiko would be a "pinch hitter," he added, the same way the previous eight empresses had been.

But where to find the right Y? During the US postwar occupation, two groups that had ensured male heirs over the centuries were abolished: other imperial branch families, like Takeda's, and concubines, who are said to have given birth to about half of past emperors.

Reacting against the panel, a cousin of the emperor, Prince Tomohito of Mikasa, 59, wrote that those two groups should be resurrected to maintain male lineage.

"I wholeheartedly support it," the prince wrote about a revival of the concubine system, "but I think that the social mood inside and outside the country may make it a little difficult."

"Unless we carefully hold and express opinions regarding 2,665 years of history and tradition, we'll move in the direction of changing Japan's `national essence,'" the prince said. "Furthermore, one day, arguments that the imperial system is not needed will even emerge."

But some supporters of the panel's recommendations say that a female line would bring badly needed equality to a society where a woman is still expected to join a man's family upon marriage, take his family name and be buried in his family's grave.

For most of the throne's history, emperors lived quietly in Kyoto. But during the Meiji Restoration of the late 1800s, as Japan tried to modernize and catch up with the West, Emperor Meiji was brought to the forefront to try to unify Japan; his grandson, Emperor Hirohito, who died in 1989, was considered divine until Japan's defeat in World War II.

Mikiyo Kano, a professor of women's history at Keiwa College, said that after Meiji, the emperor and his wife were held up as models for the Japanese. Starting with Meiji and until Japan's defeat, emperors dressed in military uniforms, while their wives promoted the Red Cross and patriotic associations.

"I think the male succession system in the imperial family has led to the discrimination and oppression of women in general in Japan," Kano said.

A female line would make a woman the symbolic leader of the nation and show a man deferring to her, as wives of emperors do.

"If Princess Aiko became empress, it might be a little better for the realization of the equality of men and women, rather than clinging to the male line," Kano said. "I'm basically for ending this system where wives always stand back while the emperor speaks, or walk behind him. That kind of image says a lot to ordinary people."

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Last week, Nvidia chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) unveiled the location of Nvidia’s new Taipei headquarters and announced plans to build the world’s first large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) supercomputer in Taiwan. In Taipei, Huang’s announcement was welcomed as a milestone for Taiwan’s tech industry. However, beneath the excitement lies a significant question: Can Taiwan’s electricity infrastructure, especially its renewable energy supply, keep up with growing demand from AI chipmaking? Despite its leadership in digital hardware, Taiwan lags behind in renewable energy adoption. Moreover, the electricity grid is already experiencing supply shortages. As Taiwan’s role in AI manufacturing expands, it is critical that