It will take months for the French government to recover from the political fallout of its handling of August's heat wave which killed about 11,400 people. It will take far longer for politicians to come to terms with the new-found aggression of the French press.

In the space of a few weeks, the press's historically subservient approach to the government has been replaced with a new tone of vitriol. The nation's Health Minister was hounded for his failure to avert the deaths.

Even in the right-wing papers the headlines were stark. "The heat wave is killing people," Le Figaro announced on Aug. 11 -- long before the government accepted that it had a problem on its hands, and days before French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin and French Health Minister Jean-Francois Mattei saw fit to abandon their holidays.

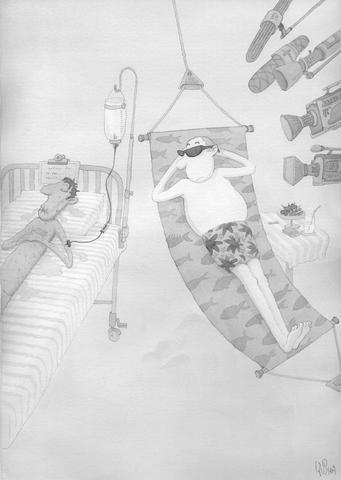

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

"A national health-care catastrophe," Le Parisien warned two days later. Judged by its own more forthright standards, the left-wing daily Liberation was unrestrained in its criticism, covering its front page with the words, the "Government Under the Grill," orange flames curling around each letter.

The gravity of the situation combined with the sluggish official response triggered howls of fury from the media, which demanded an official inquiry. Media analysts have begun asking whether the troubled summer will mark a revolution in the traditionally restrained and complicit nature of the French media.

Daniel Schneidermann, France's leading media commentator and a columnist for Le Monde, said: "I can't remember an occasion on which the press responded in such a critical way. They were pugnacious to a degree that is extremely unusual in France, even if by the standards of the British press there was nothing remarkable about its coverage. I found it extremely surprising."

Despite the mounting death toll, French President Jacques Chirac decided not to cut short his holiday in Canada. He expressed his sorrow at the deaths of UN workers in Iraq but made no comment on reports that thousands were dying in France. The newspapers responded with bemused outrage.

Country in shock

Jacques Esperandieu, deputy editor of the mild-mannered mid-market tabloid Le Parisien, said the paper had no choice but to adopt a hard-hitting stance reflecting the public's response. "Ours is not a political paper, and we didn't seize on this as an opportunity to criticize the president. However, we sensed that the country was shocked by his delay in even commenting on the crisis and we had to reflect that."

The way that the heat wave was handled laid bare the extent of the political power vacuum that reigns in France every August. Newspaper offices and television studios, obliged to continue reporting on a daily basis, saw the impending catastrophe long before any senior politician did, simply because almost all of the government was on holiday.

Turning point

Oliver Costemalle, media correspondent for Liberation, explained: "When the heat wave began to turn bad, newspapers devoted all their energy, staff, resources and space to covering it."

The turning point came with the broadcast interview with the Health Minister on Aug.11, ten days after the record-breaking temperatures began to sweep through France and just as news of the first deaths was emerging. Jean-Francois Mattei was shown in a T-shirt, in the garden of his villa in the south of France, flatly dismissing reports of an impending catastrophe. His words were transmitted immediately after reports showing doctors in Paris unable to cope with the sudden influx of heat victims and funeral workers complaining that they were having problems burying the bodies fast enough.

Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin echoed this casual approach in a statement from his Alpine holiday home. Costemalle said: "People were horrified at the contrast between the gravity of the situation unfolding in Paris and Mattei's relaxed air, in the garden, in his shirtsleeves, somewhere on the Cote d'Azur -- this was what triggered the much tougher approach to the government."

Because the government's most senior representatives were all away, there was no rapid reaction unit on hand to respond to the flood of bad news. Newspapers and television reports had no choice but to report the government's vociferous critics without balancing their words with an official response. The negative headlines mounted.

Significantly, the most powerful figures in the French media timed their holidays to coincide with the departure of the political elite, and this may also have led to a harder approach. France's newspaper editors have always enjoyed uncomfortably close ties with the political establishment; most are former political correspondents and have spent decades working alongside the people they write about.

Schneidermann believes this helps explain the media's traditional reluctance to launch outright attacks on the government. "Most of them use the familiar form tu when they address each other. These people lunch together, take holidays together, have affairs with each other. Once you've established this kind of relationship, it's much harder to be critical," he said. The fact that the editors too were away meant the more junior reporters felt no constraints in their coverage.

Costemalle agrees: "There was no one with concerns about their personal relationship with the government to put the brake on. Journalists were much freer to be as critical as they wanted."

The French government's alarm at this new phenomenon of a ferocious media is evident in the defensive measures it has taken.

Ruffled feathers

One of the Prime Minister's media handlers took the unprecedented step of making a written complaint to AFP about its use of the expression "power vacuum," complaining that this was plucked from the mouth of the socialist party leader. Another official tried in vain to force the head of France 2 to stop broadcasting footage of the Prime Minister running downstairs, pursued by journalists demanding to know why the official response had been so slow.

"For years the French media has been criticized for its reticence; this summer may mark the beginning of a shift toward the extremes of British newspapers," Schneidermann said. "They have a long way to go before they register anywhere near the British aggression on a Richter scale; but this summer we have seen the intensity of their attacks creep higher up the scale."

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization