n 1998, I visited Central Asia's former Soviet republics for talks concerning the democratic development that was -- or should have been -- taking place in those newly independent countries. My hosts were former communist leaders who were now more or less democratically elected presidents. Each spoke easily about institutions, democratic procedures, and respect for the rule of law. But human rights were another matter entirely.

In each country, I presented lists of political prisoners and asked about their fates. In one country, the president immediately decided to free a man accused of plotting a coup. But even this seeming success was morally ambiguous. The president had not made a political decision; he had bestowed a personal favor. I was receiving a gift -- itself merely another demonstration of the president's arbitrary exercise of power -- not proof of respect for moral principles.

In one country, I spoke with a leader of the Islamic fundamentalist opposition, which had waged a long civil war against the government. This man now styled himself as chairman of a "Committee of National Reconciliation." Guards armed to the teeth surrounded him, yet he firmly supported the notion of democratization. Indeed, he saw it as his surest route to power, because the vast majority of the population thought exactly as he did.

Democracy, he hinted more ominously, would enable him to "eliminate" -- he did not dwell on the exact meaning of the word -- those who did not.

In such democracies without democrats, "human rights" are more problematic to discuss than procedural formalities, because they are not thought of as "rights" in the legal sense, but merely as pangs of conscience, or else as gifts to be exchanged for something else of value. This distinction matters because it points to the limited effectiveness of formalized legal norms as a means of promoting human rights.

This gap between human rights and the behavior of rulers has brought about the greatest shift in the conduct of international affairs in our time -- the advent of "humanitarian intervention." It arose initially outside established international institutions and the UN system, originating with the French group, Doctors Without Borders, which deemed human rights to be a value superior to national sovereignty.

Doctors Without Borders introduced the concept of "the right of intervention" in humanitarian disasters, bypassing the strictures of traditional international law.

The international system rather quickly adopted (and transformed) this notion, and numerous humanitarian military interventions followed -- in Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, East Timor, and Sierra Leone. As a rule, such operations were conducted under the Security Council's mandate. A notable exception was NATO's intervention in Kosovo, which was not explicitly sanctioned by the UN.

The Kosovo intervention was also notable in another way: its legitimation was entirely moral in character, responding to the Milosevic regime's ethnic cleansing campaign, which had created a real threat of yet another immense humanitarian disaster.

NATO's intervention in Kosovo is a precedent that US Secretary of State Colin Powell used to justify the war with Iraq. But, however compelling the cause of humanitarian military intervention, such actions must be brought under the umbrella of the UN Charter. Promoting respect for human rights was, after all, the guiding principle behind the UN's establishment. Its tasks in this area were affirmed in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which give human rights legal supremacy over the sovereignty of individual states.

Yet a glaring contradiction exists between the univerality and supremacy of human rights and the principles of sovereignty and non-interference in states' internal affairs, which are also enshrined in UN documents.

One way to overcome this chasm is to introduce into the UN Charter a new chapter devoted to human rights and to reformulate Chapter IV, which concerns the use of force in international relations.

Moreover, the principle of sovereignty itself needs redefinition. What the world needs is a system of legal injunctions -- bilateral and multilateral agreements, as well as appropriate monitoring and supervisory institutions -- to regulate the use of force for humanitarian reasons.

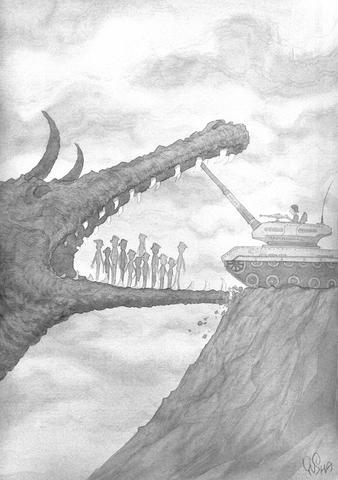

Legal restraints on humanitarian intervention are necessary because dictators too often use it to justify criminal aggression. Adolf Hitler minted this strategy when he dismantled Czechoslovakia -- supposedly in defense of the Sudeten Germans -- and later when he invaded my homeland, Poland. As Milosevic showed again in the 1990s, when he claimed to be defending innocent Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia, justifying military intervention solely on the basis of moral principles leaves too much room for their distortion and abuse.

This is why debates about reforming the Security Council should focus not on changing its composition, but on its mission. The council should be made explicitly responsible for "human security" and be given a responsibility to protect it, in addition to its current role in safeguarding more traditional notions of international security.

The principle of non-intervention in a state's internal affairs was never absolute, and globalization confronts it with a radical challenge. The term "international relations" assumes the Westphalian order of commitments among sovereign nation states, which replaced the medieval order of communities defined by personal fealty to a king.

But today it is the Westphalian order that is in decline, along with the significance of state borders. In this wider and uncertain context, the need to regulate humanitarian military intervention looms large.

Bronislaw Geremek, a historian and one of the main advisers to the Solidarity movement before 1989, was Poland's foreign minister between 1997 and 2000.

Copyright: Project Syndicate.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That