Japan now poses the great threat to world financial stability. Once again, its economy is in recession, its budget deficit huge, its public debts including unfunded pensions, worse than anywhere else in the world. With over-regulation unchecked and the private sector mired in a debt swamp, entrepreneurship can't be relied upon to stimulate change.

If Japan were an emerging economy, indeed, we would be looking for collapse and the IMF to move in to restore normality. But Japan is no Argentina or Turkey; it is the third largest economy in the world. Its stagnation and fiscal bleeding present a dramatic challenge to world stability.

Why isn't the world more alarmed? First there remains a belief that Japan, having so impressed everyone over the past 50 years, simply cannot be a basket-case. Perhaps it is only troubled, like IBM once was. If it pursued the right measures a comeback would surely follow. After all, wasn't America dysfunctional in the early 1980s only to boom in the 90s after curing its ills?

The question then is: can Japan's popular and reform-minded new Prime Minister Junichero Koizumi turn things around? Can he improve public finance, clean up the private financial infra-structure and open up the supply side? If he can do these three things, Japan can then rely on its human capital and high level of adaptability to move out of trouble. But these are three difficult tasks to tackle if you are leading an economy mired in recession and confront a political establishment adamantly opposed to reform.

So far, Koizumi is running on high octane; he has wide support and the central scenario is that tightening the budget during a recession will slow though it will not arrest the growth of debt relative to GDP and that other reforms will begin to create an improved business environment. Koizumi recognizes that, in a recession economy, these steps are difficult and risky. Herbert Hoover, America's president of 70 years ago, became famous for trying to do what prime minister Koizumi now wants todo. Although he understands this risk, Koizumi seemingly is not stinting on his commitment to do what he has promised.

True, Koizumi has announced that, if Japan's economy deteriorates sharply,in part as a result of his reform measures and budget cuts, he will take"bold flexible measures." The trouble is, there are no such measures at his disposal. Is he aware of that? I doubt it.

A big depreciation of the Yen would undoubtedly stimulate trade, but becauseJapan is a very closed economy (like Europe and the US), it will also quickly incite a bond and stock market crises, raising interest rates and causing Japanese finances to deteriorate even more. Private investor/business confidence might then fall from the prospect of inflation and with that consumption.

So a devaluation strategy will likely turn out to be a blunder. Thankfully, that seems to be the view at the Bank of Japan, which is fortunate for the rest of the world because corrective measures would be taken quickly if Koizumi's reforms cause recession to plummet into depression. What other flexible measures might there be? Public works programs of those in the 1930s might be enacted, but that is good for jobs, not the budget.

In any case, it is unlikely that Koizumi will get the chance to pursue the 5 or 10 year program of reform necessary to return the Japanese economy to normal growth. It will take that long, we know, from the US' experience in the 1980s. The trouble is that Koizumi's political mandate is not enough, and that public enthusiasm for his program has failed to recognize that, at the start, it will deliver higher unemployment and no growth.

For investment thats create new jobs is something that comes only much later.

The US went through a lot of pain throughout the 1980s, but it was only in the 1990s that the new jobs of the new economy started to show up. We are seeing this pattern in Japanese corporations that have started restructuring but continue to retrench on investment. Opening up the economy will make the recession worse, which will crimp Koizumi's popularity even more.

What can stabilize the public debt? Japan's budget needs to shift to debt reduction by some 10 percent of GDP -- and that in an economy already in recession! What would be the impact of cleaning up the balance sheets of Japanese banks? The estimates suggest a 1 to 2 percent extra dip in the growth rate with no certainty that higher growth will ever follow. These are not measures with the ring of political success.

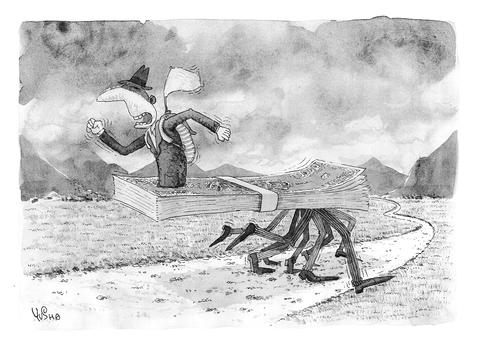

Far more likely than Koizumi undertaking sustained bold action, we will see a master at communications -- a talent vital to sustaining public confidence -- and marginal reformer shift money from construction (the sector that supports Koizumi's political adversaries) toward high tech where all of Japan is placing its hopes. In financial restructuring much of what will be done will only involve moving the furniture -- that is, shifting responsibility for debts from one institution to another. As to the Yen, we will likely see weakness but, barring world economic problems, not collapse any time soon. So no big boost will come from exports.

Despite today's hopes, sad to say, Japan is likely to remain a great risk for the world economy. It will take a few years to reach a frightening level of crisis, but Japan seems determined to get there.

In the meantime, notwithstanding the rhetoric, there won't be growth and Japan's finances will keep deteriorating even from today's levels, in which government paper has junk bond status.

Rudi Dornbusch is Ford Professor of economics at MIT and a former chief economic advisor to both the World Bank and IMF.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, July 2001

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

Taiwan People’s Party Legislator-at-large Liu Shu-pin (劉書彬) asked Premier Cho Jung-tai (卓榮泰) a question on Tuesday last week about President William Lai’s (賴清德) decision in March to officially define the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as a foreign hostile force. Liu objected to Lai’s decision on two grounds. First, procedurally, suggesting that Lai did not have the right to unilaterally make that decision, and that Cho should have consulted with the Executive Yuan before he endorsed it. Second, Liu objected over national security concerns, saying that the CCP and Chinese President Xi