Taiwan entered Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Seoul in 1991, two years after the inception of the fledgling forum, together with the People's Republic of China (PRC) and Hong Kong, marking the first occasion that the three met in an official, multilateral capacity.

For a politically isolated and yet economically active country like Taiwan, the occasion was a diplomatic triumph as APEC has remained the first -- and the only (by far) -- intergovernmental establishment to which Taiwan has been admitted since its diplomatic isolation in the 1970s.

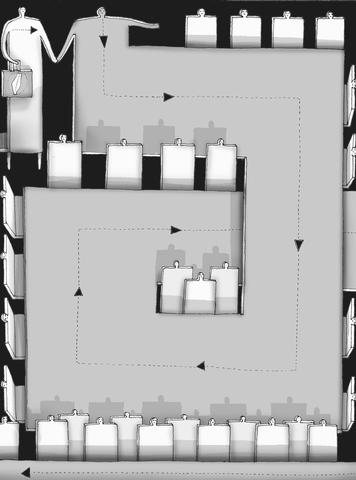

Illustration: Mountain People

"Considering Taiwan's withdrawal from the United Nations and the subsequent removal of its membership in various international organizations, Taiwan's entry into APEC is an opportunity hard to come by," recalled Chiang Pin-kung (江丙坤), then-vice minister of economic affairs, during an interview with the Taipei Times on Oct. 26.

"Taiwan's admission into APEC is a product of compromise between Taiwan's economic strength and `international reality,'" said Chiang, currently the president of the KMT's think tank, National Policy Foundation.

The former senior trade official referred "international reality" to the international community's wide support of the PRC's "one China" principle, which has constantly constrained Taiwan's membership of international organizations.

"The issue was constant -- that is, would China agree to it? Then there would be negotiations on the language -- how would Taiwan be described," said Richard H. Solomon, the then-US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, in an interview conducted in 1998.

But then why did China hold "the most flexible stance," as described by the then China's foreign minister Qian Qichen (

Various interrelated factors, in economic and political terms, led to Taiwan's entry into APEC, insiders and observers said.

Related rules set up by APEC to accommodate the admission of "three Chinas" (referring to Hong Kong, Taiwan and China) helped smooth the process, and incentives offered by APEC to both China and Taiwan made their concessions on the negotiation table possible.

Furthermore, the convergence of interests of other players involved -- including the US and South Korea officials as well as private sector players from Taiwan -- partly accelerated the process, and an exercise of creative ambiguity -- as vindicated in related memorandums of understanding (MOUs) also helped conclude related negotiations.

The three Chinese economies were denied admission as APEC's founding members in 1989 because of the longstanding sovereignty row between Taiwan and China, differences over the terms of admission, as well as the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

Nine rounds of related negotiations took place from October 1990 to October 1991, the then-vice foreign minister John Chang (

Taiwan negotiated with South Korea for three times; the rest of the negotiations were conducted between Korea, Taiwan and China in a "simultaneous but non-overlapping manner," Chang said in the legislature nine years ago. And just before the APEC's senior officials meeting (SOM) to be held in Korea in August 1991, Beijing and Taipei accepted a compromise option put forth by Lee. Lee subsequently circulated the proposal to other APEC members, who unanimously endorsed it, renowned Japanese journalist Yoichi Funabashi wrote in his book Asia Pacific Fusion: Japan's Role in APEC.

In mid-October 1991, both China and Taiwan signed respective MOUs with South Korea, and Taiwan agreed to entered APEC under the title of "Chinese Taipei" and Taiwan agreed that its foreign minister and vice foreign minister should not attend APEC meetings.

Accommodating Rules

Two decisions made by APEC before the related negotiations began were to prove pivotal in helping bring Taiwan into APEC.

The first was that since its inception in 1989, APEC has been defined as a forum composed of "economies" rather than "states." Veteran APEC participants dubbed the decision as a "conscious" move made by APEC in order to keep the door open for Taiwan and Hong Kong. "It was clearly designed to make it possible for Hong Kong and Taiwan to be involved," admitted an American participant.

The second decision, made during the May 1990 SOM, stipulated the simultaneous participation of the three entities.

Insiders said the rule, in hindsight, imposed severe pressures on China. As the then-foreign minister Frederick Chien (

Once China concluded that the price of exclusion from the first intergovernmental forum in the Pacific Rim was too high, then China had no choice but play by the rule.

APEC as a Magnet

And as William Mark Habeeb argued in his book entitled Power and Tactics in International Negotiation, "all negotiations involve concessions and all successful negotiations involve convergence."

Negotiations over Taiwan's entry into APEC are no exception. Though of different orders, both China and Taiwan made certain concessions throughout the negotiation, finally reaching a convergent point from their initially disparate positions. Arguably, these concessions were to a large extent driven by political and economic incentives offered by APEC.

For Beijing, its greatest concession was to consent to Taiwan's separate membership of APEC, agreeing to a format that would allow dual Beijing-Taipei membership of an intergovernmental unit.

And over the course of years, Beijing had shifted its attitudes toward Taiwan's membership of APEC. Before APEC formally began in November 1989, Beijing leaders told visiting Australian envoy Richard Woolcott in May of the same year: "if the meeting is to be held at a formal, intergovernmental level, then only sovereign states should participate," a clear move to keep Taiwan out of the proposed forum.

Then in the initial rounds of negotiations, Beijing gave consent to Taiwan's separate membership on condition that Taiwan joined APEC as a province of China. Consequently, however, Beijing yielded by agreeing to terms that allowed Taipei to take part in APEC, yet terms that did not necessarily imply that Taiwan was a province of China. Nonetheless, Beijing still managed to limit the "political" presence of Taipei in APEC by ruling out the participation of Taiwan's foreign minister and vice foreign minister in APEC.

Chinese officials admitted that the strong incentives offered by APEC -- in political and economic terms -- were part of the major reasons for China's concession.

"China did not want to and indeed could not be left out of any process that led to greater regional economic cooperation and development," a Chinese official was quoted in a book entitled New Taiwan, New China: Taiwan's Changing Role in the Asia-Pacific region.

In economic terms, China as the perceived growing economic power saw its admission to APEC, which then held a strong ambition to push the Uruguay Round world trade talks, as a move accorded with the country's outward-oriented economic reforms, a Chinese official said during the 1991 Seoul meetings. Arguably, China saw its aggregated economic interests in becoming an insider rather than an outsider of APEC.

In political terms, for the then relatively isolated and weakened China, a state stemming from the Tiananmen massacre that shattered its international standing in the West and the Soviet-US detente that largely reduced China's strategic value to the West, admission to APEC served as a desirable political asset.

Observers have agreed, in retrospect, that China's admission to the APEC family marked the power's return to the international community after the Tiananmen crisis.

Furthermore, despite still a fledgling regime in the early 1990s, APEC nonetheless crated a regional setting in which Beijing could pursue its bilateral diplomacy outside of formal meetings. For instance, after its admission to APEC in Seoul, China met the-then Korean president Roh Tae-woo and the Korean cabinet members in Seoul to discuss bilateral issues, thereby paving the way for the Beijing-Seoul diplomatic normalization in 1992.

As for Taipei, it yielded mainly in the title and level of representation for its delegation to APEC. Taipei's top priority from the outset was very clear -- to join rather than to stay outside of the APEC, an attitude firmly held by government officials as well as business leaders such as Koo Chen-fu (

Chien pointed out in a 1997 interview: "There is a total consensus in the government that we should participate ... The only concern is how we can reduce damages to our country to the minimum."

In economic terms, Taiwan as an aggressive export maximizer had benefited a lot from an open trading system, and APEC as a regional grouping aiming at maintaining that system thus served Taiwan's interest. Like China, Taiwan also saw its inclusion in APEC as a way to manage its interdependence with the neighboring countries. And the goal of APEC toward trade liberalization largely fitted into Taiwan's domestic economic objective towards liberalization.

As for political incentives, APEC created both symbolic and substantive gains for Taiwan. Symbolically speaking, the act of entering into a new intergovernmental organization would enhance "Taiwan's visibility," argued Chiang. On the substantive political gains offered by APEC, Taiwan foresaw its opportunity to establish high-level bilateral channels with APEC members, channels largely blocked since Taiwan lost its recognition by a majority of members in the interstate system in the 1970s.

In sum, driven by perceived gains in their future participation in APEC, arguably both Taipei and Beijing put participation as the first priority before or over the course of the one-year negotiations. Henceforth, both were ready to yield in order to achieve their top priority.

Arguably, other players involved -- especially South Korea and the US officials as well as business elite from Taiwan -- were driven by different interest calculation to join the diplomatic game, and their efforts were deemed conducive to Taiwan's admission.

South Korea's mediation was deemed critical to Taiwan's entry into APEC. Analysts said Korea's success was based on two elements: the unique Taipei-Seoul-Beijing relations as well as the well-respected diplomatic skills of Lee See-young, now the country's ambassador to the UN.

First, Seoul at the time was the only country in APEC that still maintained diplomatic ties with Taipei, and this made Taipei-Seoul diplomatic channels much closer than those between other APEC members and Taipei.

Furthermore, Seoul was eager to normalize its relations with Beijing then, and this made Korea a less confrontational negotiating partner to Beijing than the major APEC powers such as the US and Japan would have been.

Second, Lee's polished diplomatic skills were deemed important in helping broker an agreement. "SY (referring to Lee) had a full craft in dealing with his Chinese counterparts, and his demonstrated objectivity in finding a solution was assumed to win the respect of parties negotiating the deal," a former US official who was in close contacts with Lee during the negotiations recalled in 1998.

After all, as the host of the 1991 APEC meeting, Korea saw the first APEC enlargement, if achieved, as a way to enhance its international reputation. Moreover, arguably Korea saw the overall process as a way to accelerate Seoul-Beijing normalization, which was part of its moves towards Nordpolitik -- to move close to Beijing and Moscow so as to gain an upper hand in its relations with North Korea.

The abundant returns to Korea were later vindicated by the Seoul-Beijing joint communique on establishing formal relations on Aug. 24, 1992, only nine months after the Seoul meeting.

As for the US, Taiwan's then-ambassador to the US Ding Mao-shih (

Like Korea, the US perceived its national interests in supporting Taiwan's admission, both in economic and strategic terms.

In the economic sphere, the US saw the importance to include the three entities because of their strong regional links and their individual comparative advantages that could be of use to other APEC members.

At the strategic level, Robert Fauver, the then-deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, said the US intended to maintain a strategic balance within the region, so "having one [China] without the other [Taiwan] would cause problems."

"To isolate Taiwan from APEC would have been unfortunate to the regional stability and development both economically and strategically," Fauver said.

Arguably, the US' deliberate effort to remain behind the scenes to assist Korea to work in the front was also partly linked to its strategic consideration.

By staying behind the scenes in pushing for the enlargement, the US intended to avoid a direct Sino-US confrontation. And the US chose Korea as the "stalking horse" because it perceived Korea as a reliable ally in the region, and because it intended to assist Korea in strengthening ties with China through the negotiation process.

After all, Seoul's then-Nordpolitik was to gain an upper hand in its relations with North Korea, and this policy echoed the US strategic interest to establish a counterforce against the North Korea. Henceforth, the US was willing to help Korea become the mediator in order to move Seoul and Beijing together.

Apart from government officials, business leaders in Taiwan, especially Koo, had made use of regional non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to lobby for Taiwan's admission, and also utilized their private connections to gain acceptance as Taiwan's unofficial representatives in dealing at the official level.

For instance, Koo used his position as the then-international chairman of the Pacific Basin Economic Council (PBEC) to gain entrance to the opening banquet of the 1989 APEC meetings.

While Wu Tzu-dan (

The final factor that contributed to Taiwan's admission to APEC was the creative solution found, which was embodied in the MOUs.

First, "Chinese Taipei" -- the title for Taipei delegation agreed in the MOUs -- offered ample room for respective interpretation by both Taipei and Beijing.

The name was accepted because both parties could choose to translate this English title for Taipei delegation into a different version of Mandarin so as to echo their respective perception of the status of Taipei.

On the one hand, the PRC chose to call Taipei "Chung-kuo Taipei (

On the other hand, the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan chose to call itself "Chung-hua Taipei (

Finally, certain face-saving formulas were found for China in some part of the MOUs, thereby ensuring Taiwan's admission to the APEC. For instance, both agreed that Taiwan's foreign minister and vice foreign minister should not attend APEC meetings. Beijing limited the presence of Taiwan's foreign minister in APEC because it was a post regarded by Beijing as a symbol of Taipei's status as a sovereign state.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That