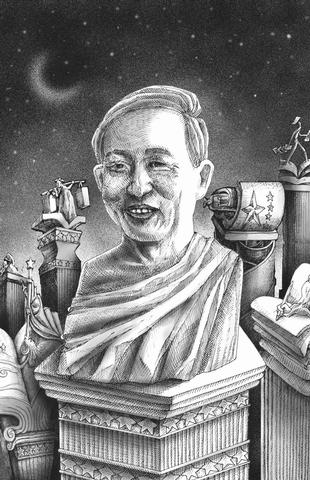

The Swedish Academy has bestowed the first Nobel Prize in literature of the new century on the exiled Chinese novelist and playwright Gao Xingjian (

After the death of Mao Zedong (

Having studied French literature in Beijing's Foreign Language Institute before the Cultural Revolution, Gao was one of the first Chinese to become acquainted with Western modernism. His plays represent a lofty ambition to start a trend in China to break away from the restrains of both traditional Chinese prose and the Communist literary mentality. He used Western techniques to manifested the absurdity of China's reality in his plays such as Absolute Signal (

After Tiananmen he wrote the play Fugitives (

heretic

In Fugitives, he also expressed through the play's protagonists his contempt for the hollow concepts of "people," "country" and "collective will," all concepts that flooded Chinese literature not only during the communist era but throughout the 20th century. The play has one central theme, that trying to escape is human destiny. Obviously, this theme, as the themes in many of his plays and other writings, is heretical to China's authorities. But Gao's work is not trammeled by its Chinese background.

The background and characters of Fugitives could be easily replaced by another setting or group of protagonists. The aspirations of the characters in the play are to be met in every society, and it is for this reason that Gao's work can be said to be "an oeuvre of universal validity," as the Swedish Academy acknowledged.

Even though Fugitives was seen as a political play by the Chinese authorities, condemned in the official media and banned in China, Gao declared he had no intention to use literature to express political ideals.

"I write simply because that, as a human being, not merely as a Chinese, I want to prove my existence," he wrote.

But he also believes that "faced with political and social oppression, one must resist and rebel." Therefore, he publicly declared after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre that he "would not go back to the so-called motherland as long as it remains under a totalitarian regime."

Gao's most weighty work so far is Soul Mountain, (

"I have put all the memories of my youth, my thoughts and my doubts about Chinese culture into that book," Gao has said. However, this modern Western-style work of art failed to attract any attention at all in Taiwan where traditionalism continues to dominate.

Another work of his, One Man's Bible (

Also, though refreshing in style and rich in the use of the Chinese language, some of his works lack the originality that masterpieces should display; sometimes they can seem too derivative of Western literary works and forms.

Nevertheless, his daring inspires reflection about being not only a Chinese but a human being, and his robust rejection of writing to support an ideology, be it nationality, motherland or the masses, but rather writing in search for satisfaction of the needs of one's soul may truly be considered refreshing for Chinese.

Following is a list of winners of the Nobel Prize in literature since 1975. The prize was first awarded in 1901.

2000 Gao Xingjian (China)

1999 Guenter Grass (Germany)

1998 Jose Saramago (Portugal)

1997 Dario Fo (Italy)

1996 Wislawa Szymborska (Poland)

1995 Seamus Heaney (Ireland)

1994 Kenzaburo Oe (Japan)

1993 Toni Morrison (US)

1992 Derek Walcott (Trinidad)

1991 Nadine Gordimer (South Africa)

1990 Octavio Paz (Mexico)

1989 Camilo Jose Cela (Spain)

1988 Naguib Mahfouz (Egypt)

1987 Joseph Brodsky (US)

1986 Wole Soyinka (Nigeria)

1985 Claude Simon (France)

1984 Jaroslav Seifert (Czechoslovakia)

1983 William Golding (Britain)

1982 Gabriel Garcia Marquez (Colombia)

1981 Elias Canetti (Britain)

1980 Czeslaw Milosz (United States)

1979 Odysseus Elytis (Greece)

1978 Isaac Bashevis Singer (US)

1977 Vicente Aleixandre (Spain)

1976 Saul Bellow (US)

1975 Eugenio Montale (Italy)

Cao Chang-ching (

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe (VE) Day, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) made a statement that provoked unprecedented repudiations among the European diplomats in Taipei. Chu said during a KMT Central Standing Committee meeting that what President William Lai (賴清德) has been doing to the opposition is equivalent to what Adolf Hitler did in Nazi Germany, referencing ongoing investigations into the KMT’s alleged forgery of signatures used in recall petitions against Democratic Progressive Party legislators. In response, the German Institute Taipei posted a statement to express its “deep disappointment and concern”