Mao Zedong

Not long ago, I published a short essay about idealism. In the essay, I wrote "I used to believe in Marxism. And what really makes me angry is that my youthful idealism was raped by people like Stalin and Mao."

"Rape" is a very strong word and I might have gone too far to use it in my essay. But many people at my age, including my leftist American friends, have the same feeling -- we were all cheated because we were young and naive. Nonetheless, we are still very curious about the personality and behavior of Mao.

Some people in China still speak very highly of him. But they might not mean what they say -- a reflection of the typical hypocrisy of the people in power.

Two views of Mao

Two new biographies of Mao have recently been published. One is Mao Zedong by the well-known scholar and author Jonathan Spence; the other is Mao: A Life by British journalist Philip Short.

Spence's book is part of the Penguin Lives Series, and is very short, just 188 pages, while Short's biography runs 782 pages. Despite the differing lengths, both authors have attempted to objectively analyze Mao.

They both focus their attention on how Mao transformed a divided country -- one subject to foreign control with a stagnant economy and low international status -- into a strong world power.

Neither denies Mao's contribution to the achievements of the modern China: the reduction of illiteracy, brilliant economic performance and an international power due to its nuclear weapons. Both Spence and Short think China has regained the reputation it enjoyed on the international stage before the decline of the Ming Dynasty.

But we should never forget the " 10 year disaster" of the Cultural Revolution when we mention China's prosperity today. In my opinion, the "disaster" of China actually originated in the "Anti-rightist Campaign" of the early 60s and lasted at least 20 years.

Spence and Short both ask the same questions: Should we evaluate the history of China with Chinese standards or Western ones? Are Western scholars supposed to judge Mao by Western values? Communist China has pardoned Mao's mistakes, but should Western countries follow suit?

Mao's dark side

Both authors mentioned that some new material about Mao has been published recently, including memoirs written by Mao's confidants and intimate subordinates. This material reveals Mao's sinister side when he was in power; his means to suppress the dissidents was more ruthless than we previously believed.

In comparing the two biographies, it is easy to see the differing perspectives adopted by a scholar and a journalist.

Spence is considered one of the most authoritative experts on modern Chinese affairs. He is a professor at Yale University and has published over 11 books about Chinese history. Although his biography is short, it is fact-filled.

Short was a correspondent in China for The Times and the BBC and has more than 25 years experience in interviewing and reporting. He was sent to Beijing after Mao died in 1976 and looked at China from a fresh perspective.

It took him seven years to research the relevant Chinese documents for his biography. Like Spence, he has a Chinese wife, which was a big plus with translations when he was dealing with Chinese historical material.

Mao: A Life is vividly written compared to Spence's more academic work and is thus more readable. The book is filled with anecdotes. For example, Short mentions that Mao never brushed his teeth, just washing his mouth with tea. After taking up residence in Zhongnanhai

A description of Mao's bed-room, with books taking up half the space on his bed, appears in both biographies.

Short mentions that the Communist Party once proscribed extramarital sex as illegal behavior. But who would imagine that its supreme leader, long separated from his wife Jiang Qing

The common focus of Spence's and Short's biographies is the sinister side of China under Mao's ruling.

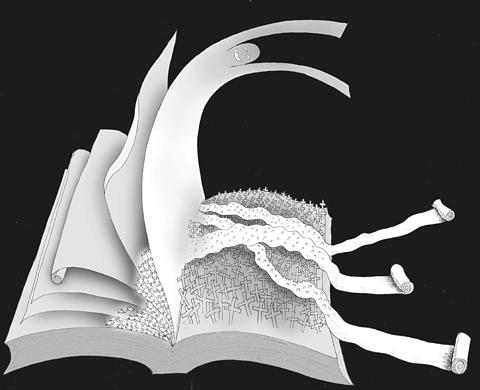

Both express their shock over the massive scale of turbulence incited by Mao. According to a figure quoted by Mao in Spence's book, about 700,000 landlords and counter-revolutionaries were killed in the "land reform movement" between 1950 to 1952. During the "Great Leap Forward" of 1960 and 1961, 20 million people died of starvation.

According to Spence, millions more died in the Cultural Revolution, while Short estimates the death toll at about 23 to 35 million.

Short concludes that Mao caused more deaths than any other political leader in world history. He says the sins of Mao were even graver than those of Stalin and Hitler.

70-30

Spence concluded that Mao's ideology derived from his youthful, idealistic infatuation with Marxism and it was not until his later years that he became a cruel tyrant who heartlessly purged his comrades. He lived like a feudal emperor -- isolated by eminence, residing in a forbidden palace and traveling by a private, totally sealed off train.

Short describes Mao as a rancorous control freak, a tyrant who mercilessly destroyed anyone who had the potential to threaten his power. Short says Mao's paranoia was far advanced in 1957 and that contributed to the "Anti-rightist Campaign" later on.

In his visit to Moscow in the autumn of 1957, Mao openly defied the threat of nuclear war in a speech to a meeting of leaders of communist countries:

"There are 2.7 billion people in the world. If a nuclear war broke out, only one-third of the population will die. And half people of the world would die if things get really bad."

Short avoids defining Mao's reaction as megalomaniacal. He just says " It would take a long time for the history to settle down over the role of Mao."

This comment is typical of the attitude of Western scholars in general; they do not like to criticize China too harshly.

From Short's point of view, however, Mao should not be compared to two other tyrants of the 20th century: Stalin and Hitler.

Short says Mao lacked Stalin's determination to "wipe out all the opponents who got on his way" and he was not another Hitler since the Nazi leader had "obliterated another race by sending them to the gas chambers."

Short argues that Mao belongs to another "realm" because his goal was to transform the whole Chinese race: "Stalin cared about what his subjects did (or might do); Hitler, about who they were; Mao cared about what they thought."

This differentiation, however, does not sound very clear to me. The only thing all three of these tyrants are remembered for is the vast numbers of people they killed. Psychologists might have to analyse how their childhoods shaped the later development of their personalities.

The conclusions of both biographies are almost the same as a document issued by the Chinese Communist Party in 1981. In the document, the party admits that Mao had made "grave mistakes," but says his accomplishments outweighed his faults, that is: "70 percent right and 30 percent wrong."

Both Short and Spence agree that Mao was a political and military genius and his talent was superior to other contemporary political figures. He led China to modernization after centuries of shame and humiliation.

But he hurt hundreds of thousands of people on the way to revolution and the people who suffered from the hardships inflicted by Mao are still struggling with the aftermath of the revolution.

China is still nominally a communist country. But Spence and Short believe that the Chinese leaders nowadays will not repeat the same mistakes as Mao, because the value of people's lives is too great to be sacrificed.

With the economic prosperity (brought about by capitalism), the two authors believe China will gradually evolve from the tyrannical rule of Mao's time to political tolerance with a certain degree of democracy.

Timothy T. S. Tung

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

On May 13, the Legislative Yuan passed an amendment to Article 6 of the Nuclear Reactor Facilities Regulation Act (核子反應器設施管制法) that would extend the life of nuclear reactors from 40 to 60 years, thereby providing a legal basis for the extension or reactivation of nuclear power plants. On May 20, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) legislators used their numerical advantage to pass the TPP caucus’ proposal for a public referendum that would determine whether the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant should resume operations, provided it is deemed safe by the authorities. The Central Election Commission (CEC) has

When China passed its “Anti-Secession” Law in 2005, much of the democratic world saw it as yet another sign of Beijing’s authoritarianism, its contempt for international law and its aggressive posture toward Taiwan. Rightly so — on the surface. However, this move, often dismissed as a uniquely Chinese form of legal intimidation, echoes a legal and historical precedent rooted not in authoritarian tradition, but in US constitutional history. The Chinese “Anti-Secession” Law, a domestic statute threatening the use of force should Taiwan formally declare independence, is widely interpreted as an emblem of the Chinese Communist Party’s disregard for international norms. Critics