Ian Falconer kept thinking about the heaps of discarded plastic fishing nets he saw at Newlyn harbor near his home in Cornwall, southern England.

“I thought ‘it’s such a waste,’” he said. “There has to be a better solution than it all going into landfill.”

Falconer, 52, who studied environmental and mining geology at university, came up with a plan: shredding and cleaning the worn-out nets, melting the plastic down and converting it into filament to be used in 3D printing. He then built a “micro-factory” so that the filament could be made into useful stuff.

Photo: Bloomberg

“Every year, up to 1 million tonnes of fishing nets are discarded,” he said. “Most of that ends up in landfill or is burned, or worse still, finds its way back into the oceans. This showed there was another way for some of that material.”

The first big challenge he encountered when he started in 2016 was getting hold of the nets, but he badgered the Newlyn harbor master into giving him a few to test his theory in his kitchen.

Since its launch the following year, Falconer’s company OrCA (previously Fishy Filaments) has raised more than £1 million (US$1.34 million) from small investors in more than 40 countries. The investment funded the development of patented new machinery that can convert more than 20kg of nylon fishing nets an hour. He said the recycling process has less than 3 percent of the carbon impact of producing new nylon.

“When they get to us, this particular type of fishing nets have typically been used by Cornish fishers for around six months,” he said. “They are routinely swapped out because their surfaces become cloudy due to wear and the buildup of an algal biofilm. With time and repeated use, eventually the fish can sense them in the water and avoid them.”

“Skippers can see their catches fall as their nets age, and it makes sense to replace them,” he added.

The nets that go into the shredder come out as small blue-green beads that Falconer sells to 3D printing companies, which convert them into strings of filament used in 3D printing. They are also sold around the world to replace new plastic in more conventional products that are made using injection molding.

Falconer’s shipping container office is full of items made from the raw material: sunglasses, light shades, bottle openers, razor blade handles. It can be used for just about anything. The items he is most proud of are those made from his nylon mixed with waste carbon fiber — mostly from offcuts of car and airplane manufacturing. This stronger and more expensive product is used to make parts for racing bikes and super-light sunglasses, and industrial components such as electronic enclosures.

The carbon and nylon mix sells for up to £35,000 a tonne — more than the £12,000 a tonne pure nylon beads.

“Our process turns a liability of about £500 a tonne to pay to get someone to take the nets away, not to mention the environmental cost of that, into something of real value,” Falconer said. “Now, when I pass the piles of fishing nets on the harborside, I see piles of money.”

Falconer’s roster of clients, which includes Philips lighting, L’Oreal, Ford and Mercedes-Benz, is increasing as more companies see OrCA’s potential to help them reduce their carbon footprint by increasing the proportion of their products made from recycled materials.

Waste fishing nets are a problem in Cornwall, but are a much bigger problem in countries without established waste systems

“The EU wants automakers to use at least 20 percent recycled plastic by 2035,” he said. “Using ours is one of the easiest ways to do it.”

Falconer could make a good living continuing to recycle Newlyn fishers’ nets, but he has wider ambitions.

“Waste fishing nets are a problem here in Cornwall, but the same type of nets are a much bigger problem in other countries, especially those without established waste systems,” he said.

About 150,000 tonnes of nylon monofilament fishing nets are made every year, and, based on external reports, Falconer estimates production would soon rise to 200,000 tonnes.

The world’s total traditional nylon recycling capacity is less than 150,000 tonnes a year, so less than half the capacity that European carmakers need to meet their targets, and almost all of that is taken up with recycling carpets and other textiles.

To try to combat the problem, Falconer plans on exporting his recycling solution to any harbor that wants it. A container with all the equipment needed to run a small recycling plant would cost about US$500,000 if built in the UK.

Falconer said he has already received inquiries from 14 countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Ghana, South Africa and Vietnam.

“The beauty of it is that it all fits in a shipping container and pretty much anyone can operate it,” he said. “So you could have one of these at every harbor around the world, converting a costly and hazardous waste into a profitable raw material.”

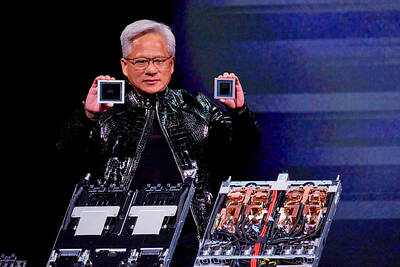

Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Monday introduced the company’s latest supercomputer platform, featuring six new chips made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), saying that it is now “in full production.” “If Vera Rubin is going to be in time for this year, it must be in production by now, and so, today I can tell you that Vera Rubin is in full production,” Huang said during his keynote speech at CES in Las Vegas. The rollout of six concurrent chips for Vera Rubin — the company’s next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) computing platform — marks a strategic

Enhanced tax credits that have helped reduce the cost of health insurance for the vast majority of US Affordable Care Act enrollees expired on Jan.1, cementing higher health costs for millions of Americans at the start of the new year. Democrats forced a 43-day US government shutdown over the issue. Moderate Republicans called for a solution to save their political aspirations this year. US President Donald Trump floated a way out, only to back off after conservative backlash. In the end, no one’s efforts were enough to save the subsidies before their expiration date. A US House of Representatives vote

REVENUE PERFORMANCE: Cloud and network products, and electronic components saw strong increases, while smart consumer electronics and computing products fell Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密) yesterday posted 26.51 percent quarterly growth in revenue for last quarter to NT$2.6 trillion (US$82.44 billion), the strongest on record for the period and above expectations, but the company forecast a slight revenue dip this quarter due to seasonal factors. On an annual basis, revenue last quarter grew 22.07 percent, the company said. Analysts on average estimated about NT$2.4 trillion increase. Hon Hai, which assembles servers for Nvidia Corp and iPhones for Apple Inc, is expanding its capacity in the US, adding artificial intelligence (AI) server production in Wisconsin and Texas, where it operates established campuses. This

US President Donald Trump on Friday blocked US photonics firm HieFo Corp’s US$3 million acquisition of assets in New Jersey-based aerospace and defense specialist Emcore Corp, citing national security and China-related concerns. In an order released by the White House, Trump said HieFo was “controlled by a citizen of the People’s Republic of China” and that its 2024 acquisition of Emcore’s businesses led the US president to believe that it might “take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States.” The order did not name the person or detail Trump’s concerns. “The Transaction is hereby prohibited,”