Lahai Makieu struck the bamboo with a machete until it cracked and fell. Balancing on his crutch, he reached to pick it up. However, colleagues pulled the bamboo’s other end, and he tumbled into the dense grass.

“They forgot I had one leg,” the 45-year-old said, laughing.

The trainer at a center for amputee farmers picked himself up and added: “We fall and we rise.”

Photo: AP

The phrase encapsulates his journey since the civil war in Sierra Leone. From 1991 to 2002, conflict in the West African country created about 28,000 amputees like him. Amputation by machete was one terror tactic by rebels.

However, even now, amputation rates remain high in Sierra Leone due to motorbike accidents, poor medical care and delayed treatment by traditional healers, medical researchers say.

The government does not collect data on amputees, but the UN estimates there are about 500,000 disabled people in the country.

Photo: AP

Makieu’s left leg was amputated as a child after rebels shot him, and he received no medical attention for a week.

More than 20 years later, in a nation ranked near the bottom of the UN development index, amputees still face discrimination, often regarded as a shameful reminder of the civil war. Many resort to begging and live in the streets.

“No one cares about you as an amputee in Sierra Leone,” Makieu said.

The Farming on Crutches initiative where Makieu works near the capital, Freetown, offers a rare refuge. It aims to restore amputees’ confidence and independence by teaching them skills to start a farm business. They have trained 100 amputees and want to expand their work.

The training has transformed Makieu’s life. After his amputation in 2002, he lived in a small room with a friend in Freetown, dependent on him for food, money and shelter.

At a displacement camp for 270 amputees in Freetown, he met Mambud Samai, the founder of Farming on Crutches and a pastor.

“Many [amputees] are being rejected by their families and communities. They don’t believe they have love,” the 51-year-old Samai said.

He felt moved to help after being a refugee himself in Guinea during the civil war.

First, Samai organized beach soccer matches for amputees in Freetown, boosting their confidence. During a visit to Sierra Leone, former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon saw the project and funded a site for an amputee soccer club outside the capital.

However, Samai decided soccer was not enough. As a farmer, he saw agriculture as a path to self-sufficiency. In 2020, he set up a demonstration farm to teach amputees how to farm and become rural leaders.

His project’s name reflects amputees’ widespread use of crutches instead of prosthetic legs in Sierra Leone. Foreign donors distributed them after the civil war, but many people say they do not fit well and cause sores. The country’s only prosthetic clinic is too expensive for many.

Makieu was one of the first Farming on Crutches trainees in 2022. He learned how to use farm waste for organic fertilizer and bamboo sticks for fences. He set up a small farm operation this year with his wife, Zanib, also an amputee. They met during the training and now have a child.

Makieu wants to inspire future farmers.

“It’s my dream to teach people about life. It’s about changing your mindset,” he said.

Morning mist rolled over the nearby mountains as the camp rose for exercises ahead of a strenuous day. They gathered in a circle, harmonizing on local songs before Samai spoke.

“We are created for fellowship, not isolation,” he said. “When we return, we are not as we came. We go home to serve our community as rural leaders.”

“I sustain my life through farming, I met my wife here. This training can be a big package for you,” Makieu said.

However, the vast majority of amputees in Sierra Leone have no such support.

Alimany Kani, 30, lives in a camp built by the Norwegian Refugee Council for amputees on the outskirts of Freetown. He lost his leg when he was a baby, to the same bullet that killed his father in the civil war. Despite holding a graduate degree in social work, he cannot find a job.

“Even if you have qualifications, an able-bodied with less education will always get the job,” Kani said.

The Sierra Leonean National Commission for Persons with Disability said that discrimination toward amputees has improved in the last decade since the Disability Act in 2011 aimed to provide equal opportunities and punish discrimination.

Kani firmly disagreed and called on the government to deliver reparations to victims of the civil war. The Sierra Leonean Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2009 recommended that amputees receive pensions, access to healthcare, accommodation and education.

However, many of those pledges remain unfulfilled, including for Kani. Only 1,300 out of 32,000 have received a full reparations package due to lack of resources, according to the UN’s International Organization for Migration.

“The government don’t keep their promises. It’s inhumane,” Kani said.

There is no specific support for amputees from the government, the National Commission for Persons with Disability said.

Sierra Leone’s health ministry, the president’s office and the National Commission for Social Action office that manages the reparations program did not respond to questions.

A farming charity in Britain, Pasture for Life, is financing Farming on Crutches in full, but Samai said they need support from the Sierra Leonean government to expand.

Meanwhile, the government is investing more than US$600 million in agriculture, but some believe this would largely benefit large-scale agriculture over small-scale farmers — such as Farming on Crutches trainees — who form 70 percent of the population.

Two such smallholders are cousins and Farming on Crutches trainees, Amara and Moustapha Jalloh, aged 19 and 21 respectively, in central Sierra Leone.

Both recently harvested rice and cassava. Moustapha, who was born without a leg, said his harvest surplus allowed him to pay for computer science training.

He dreams of being an agricultural engineer.

“Any successful story, there must be painful experiences,” he said.

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

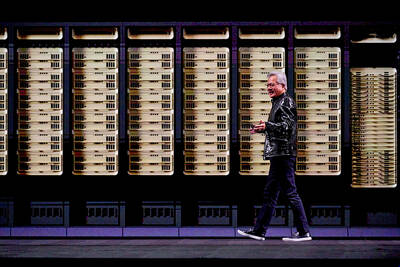

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,