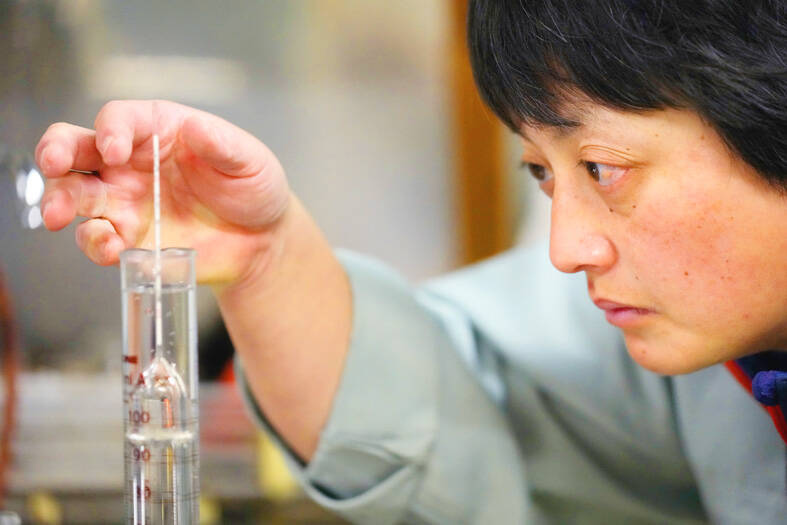

Not long after dawn, Japanese sake brewer Mie Takahashi checks the temperature of the mixture fermenting at her family’s 150-year-old sake brewery, Koten, nestled in the foothills of the Japanese Alps.

She stands on an uneven narrow wooden platform over a massive tank containing more than 3,000 liters of a bubbling soup of steamed rice, water and a rice mold known as koji, and gives it a good mix with a long paddle.

“The morning hours are crucial in sake making,” Takahashi, 43, said.

Photo: AP

Her brewery is in Nagano Prefecture, a region known for its sake making.

Takahashi is one of a small group of female toji, or master sake brewers. Only 33 female toji are registered in Japan’s Toji Guild Association out of more than a thousand breweries nationwide.

Women were largely excluded from sake production until after World War II.

Photo: AP

Sake making has a history of more than 1,000 years, with strong roots in Japan’s traditional Shinto religion.

However, when the liquor began to be mass produced during the Edo period, from 1603 until 1868, an unspoken rule barred women from breweries.

The reasons behind the ban remain obscure. One theory is that women were considered impure because of menstruation and were therefore excluded from sacred spaces, said Yasuyuki Kishi, vice director of the Sakeology Center at Niigata University.

“Another theory is that, as sake became mass produced, a lot of heavy labor and dangerous tasks were involved,” he said. “So, the job was seen as inappropriate for women.”

However, the gradual breakdown of gender barriers, coupled with a shrinking workforce caused by Japan’s fast-aging population, has created space for more women to work in sake production.

“It’s still mostly a male-dominated industry. But I think now people focus on whether someone has the passion to do it, regardless of gender,” Takahashi said.

She believes mechanization in the brewery is also helping to narrow the gender gap. At Koten, a crane lifts hundreds of kilograms of steamed rice in batches and places it onto a cooling conveyor, after which the rice is sucked through a hose and transported to a separate room dedicated to cultivating koji.

“In the past, all of this would have been done by hand,” Takahashi said. “With the help of machines, more tasks are accessible for women.”

Sake, or nihonshu, is made by fermenting steamed rice with koji mold, which converts starch into sugar. The ancient brewing technique was recognized under UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage earlier this month.

As a child, Takahashi was not allowed to enter her family-owned brewery. However, when she turned 15, she was given a tour of the brewery for the first time and was captivated by the fermentation process.

“I saw it bubbling up. It was fascinating to learn that those bubbles were the work of microorganisms that you can’t even see,” said Takahashi, who could not drink alcohol at the time, because she was underage. “It smelled really good. I thought it was amazing that this wonderful fragrant sake could be made from just rice and water. So, I thought I’d like to try making it myself.”

She pursued a degree in fermentation science at the Tokyo University of Agriculture. After graduation, she decided to return home to become a master brewer. She trained for 10 years under the guidance of her predecessor, and at the age of 34 became a toji at her family brewery.

As the brewery enters the winter peak season, Takahashi oversees a team of seasonal workers and production ramps up. It is labor-intensive work, hauling and turning large amounts of heavy steamed rice, and mixing thousands of liters of brew. The master brewer must have the knowledge and skill to carefully control optimal koji mold growth, which needs round-the-clock monitoring.

Despite the intensity, Takahashi manages to encourage camaraderie in the brewery, catching up with the team as they hand-mix koji rice side by side in a hot humid room.

“I was taught that the most important thing is to get along with your team,” Takahashi said. “A common saying is that if the atmosphere in the brewery is tense, the sake will turn out harsh, but if things are going well in the brewery, the sake will turn out smooth.”

The inclusion of women plays an important role in the survival of the Japanese sake industry, which has seen a steady decline since its peak in the 1970s.

Domestic alcoholic consumption has dropped, while many smaller breweries struggle to find new master brewers. According to the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association, today’s total production volume is about a quarter of what it was 50 years ago.

To remain competitive, Koten is among many Japanese breweries trying to find a wider market both domestically and abroad.

“Our main product has always been dry sake, which local people continue to drink regularly,” said Takahashi’s older brother, Isao Takahashi, who is in charge of the business side of the family operation.

“We’re now exploring making higher value sake as well,” Isao Takahashi said.

He supports his sister’s experiments — every year she creates a limited-edition series, Mie Special, that is meant to branch out from their signature dry product.

“My sister would say she wants to try to make low alcohol content, or she wants to try new yeasts — all kinds of new techniques are coming in through her,” he said. “I want my sister to make the sake she wants, and I want to do my best to sell it.”

WEAKER ACTIVITY: The sharpest deterioration was seen in the electronics and optical components sector, with the production index falling 13.2 points to 44.5 Taiwan’s manufacturing sector last month contracted for a second consecutive month, with the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) slipping to 48, reflecting ongoing caution over trade uncertainties, the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research (CIER, 中華經濟研究院) said yesterday. The decline reflects growing caution among companies amid uncertainty surrounding US tariffs, semiconductor duties and automotive import levies, and it is also likely linked to fading front-loading activity, CIER president Lien Hsien-ming (連賢明) said. “Some clients have started shifting orders to Southeast Asian countries where tariff regimes are already clear,” Lien told a news conference. Firms across the supply chain are also lowering stock levels to mitigate

IN THE AIR: While most companies said they were committed to North American operations, some added that production and costs would depend on the outcome of a US trade probe Leading local contract electronics makers Wistron Corp (緯創), Quanta Computer Inc (廣達), Inventec Corp (英業達) and Compal Electronics Inc (仁寶) are to maintain their North American expansion plans, despite Washington’s 20 percent tariff on Taiwanese goods. Wistron said it has long maintained a presence in the US, while distributing production across Taiwan, North America, Southeast Asia and Europe. The company is in talks with customers to align capacity with their site preferences, a company official told the Taipei Times by telephone on Friday. The company is still in talks with clients over who would bear the tariff costs, with the outcome pending further

Six Taiwanese companies, including contract chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), made the 2025 Fortune Global 500 list of the world’s largest firms by revenue. In a report published by New York-based Fortune magazine on Tuesday, Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), ranked highest among Taiwanese firms, placing 28th with revenue of US$213.69 billion. Up 60 spots from last year, TSMC rose to No. 126 with US$90.16 billion in revenue, followed by Quanta Computer Inc (廣達) at 348th, Pegatron Corp (和碩) at 461st, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) at 494th and Wistron Corp (緯創) at

NEGOTIATIONS: Semiconductors play an outsized role in Taiwan’s industrial and economic development and are a major driver of the Taiwan-US trade imbalance With US President Donald Trump threatening to impose tariffs on semiconductors, Taiwan is expected to face a significant challenge, as information and communications technology (ICT) products account for more than 70 percent of its exports to the US, Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research (CIER, 中華經濟研究院) president Lien Hsien-ming (連賢明) said on Friday. Compared with other countries, semiconductors play a disproportionately large role in Taiwan’s industrial and economic development, Lien said. As the sixth-largest contributor to the US trade deficit, Taiwan recorded a US$73.9 billion trade surplus with the US last year — up from US$47.8 billion in 2023 — driven by strong