In a cavernous production hall in Dusseldorf last fall, the somber tones of a horn player accompanied the final act of a century-old factory.

Amid the flickering of flares and torches, many of the 1,600 people losing their jobs stood stone-faced as the glowing metal of the plant’s last product — a steel pipe — was smoothed to a perfect cylinder on a rolling mill. The ceremony ended a 124-year run that began in the heyday of German industrialization and weathered two world wars, but could not survive the aftermath of the energy crisis.

There have been numerous iterations of such finales over the past year, underscoring the painful reality facing Germany: its days as an industrial superpower might be coming to an end.

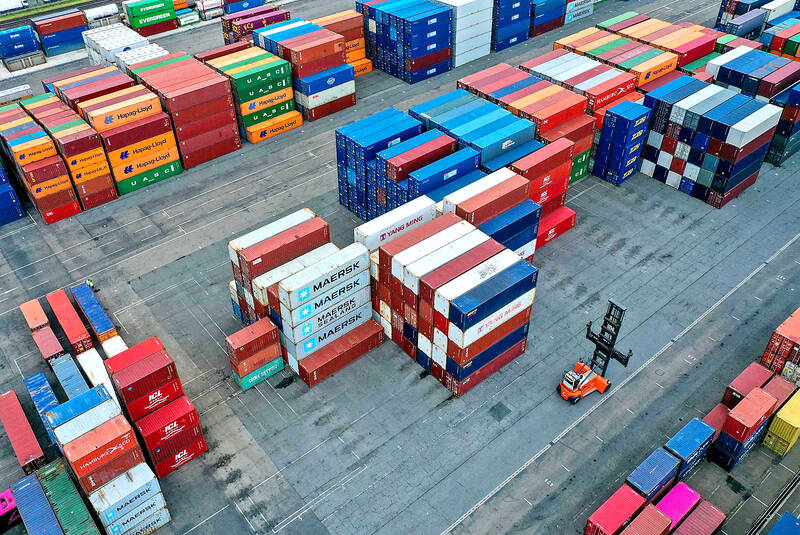

Photo: Bloomberg

Manufacturing output in Europe’s biggest economy has been trending downward since 2017, and the decline is accelerating as competitiveness erodes.

“There’s not a lot of hope, if I’m honest,” said Stefan Klebert, chief executive officer of GEA Group AG, a supplier of manufacturing machinery that traces its roots to the late 1800s. “I am really uncertain that we can halt this trend. Many things would have to change very quickly.”

The underpinnings of Germany’s industrial machine have fallen like dominoes. The US is drifting away from Europe and is seeking to compete with its transatlantic allies for climate investment. China is becoming a bigger rival and is no longer an insatiable buyer of German goods. The final blow for some heavy manufacturers was the end of huge volumes of cheap Russian natural gas.

Photo: AFP

Alongside global volatility, political paralysis in Berlin is intensifying long-standing domestic issues such as creaking infrastructure, an aging workforce and the snarl of red tape.

Germany’s education system, once a strength, is emblematic of a long-term lack of investment in public services. The Ifo research institute estimates that declining math skills will cost the economy about 14 trillion euros (US$15 trillion) in output by the end of the century.

In some cases, the industrial downshift is taking place in small steps like scaling back expansion and investment plans. Others are more evident like shifting production lines and trimming staff. In extreme instances — like Vallourec SACA’s pipe plant, once part of fallen industrial giant Mannesmann AG — the consequence is permanent closure.

Germany still has an enviable roster of small, agile manufacturers, and the Bundesbank and others reject the notion that full-blown deindustrialization is anywhere close. But with reforms stalled, it’s unclear what will slow the decline.

“We are no longer competitive,” German Minister of Finance Christian Lindner said at a Bloomberg event earlier this month. “We are getting poorer because we have no growth. We are falling behind.”

Fading industrial competitiveness threatens to plunge Germany into a downward spiral, Michelin SCA northern Europe head Maria Rottger said. The French tiremaker is shutting two of its German plants and downsizing a third by the end of next year in a move that will affect more than 1,500 workers. US rival Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co has similar plans for two facilities.

“Despite the motivation of our employees, we have arrived at a point where we can’t export truck tires from Germany at competitive prices,” she said in a recent interview. “If Germany can’t export competitively in the international context, the country loses one of its biggest strengths.”

Other examples of decline surface regularly. GEA Group is closing a pump factory near Mainz in favor of a newer site in Poland. Autoparts maker Continental AG announced plans in July last year to abandon a plant that makes components for safety and brake systems. Rival Robert Bosch GmbH is in the process of slashing thousands of workers.

The energy crisis in the summer of 2022 was a major catalyst. While worst-case scenarios like freezing homes and rationing were avoided, prices remain higher than in other economies, which adds to costs from higher wages and regulatory complexity.

Germany’s sluggish bureaucracy also is not keeping pace, even when companies are prepared to invest. GEA installed solar capacity at a factory in the western German town of Oelde, where it makes equipment that can separate cream from milk. It applied for permits to feed in the power in January last year, two months before starting construction and is still waiting for approval — nearly two years after initiating the project.

Furthermore, China is now causing trouble for Germany in a number of ways. On top of its strategic shift into advanced manufacturing, a slowdown of the Asian superpower’s economy is sapping demand for German goods even further. At the same time, cheap competition from China is worrying industries key for Germany’s climate transition — and not just electric cars.

Germany’s headwinds require adaptation. For EBM-Papst, a producer of fans and ventilators, the industrial crisis meant acquiring a struggling supplier. And to stay nimble, the company shifted production to components for heat pumps and data centers and away from the auto sector. It’s also looking to move some administrative tasks to eastern Europe or India.

“It’s not just energy,” EBM-Papst CEO Klaus Geisdorfer said in an interview. “It’s also staff availability in Germany, which is now very tense.”

Within a decade, the working-age population will be too small to keep the economy functioning as it does today, he added.

GROWING OWINGS: While Luxembourg and China swapped the top three spots, the US continued to be the largest exposure for Taiwan for the 41st consecutive quarter The US remained the largest debtor nation to Taiwan’s banking sector for the 41st consecutive quarter at the end of September, after local banks’ exposure to the US market rose more than 2 percent from three months earlier, the central bank said. Exposure to the US increased to US$198.896 billion, up US$4.026 billion, or 2.07 percent, from US$194.87 billion in the previous quarter, data released by the central bank showed on Friday. Of the increase, about US$1.4 billion came from banks’ investments in securitized products and interbank loans in the US, while another US$2.6 billion stemmed from trust assets, including mutual funds,

Micron Memory Taiwan Co (台灣美光), a subsidiary of US memorychip maker Micron Technology Inc, has been granted a NT$4.7 billion (US$149.5 million) subsidy under the Ministry of Economic Affairs A+ Corporate Innovation and R&D Enhancement program, the ministry said yesterday. The US memorychip maker’s program aims to back the development of high-performance and high-bandwidth memory chips with a total budget of NT$11.75 billion, the ministry said. Aside from the government funding, Micron is to inject the remaining investment of NT$7.06 billion as the company applied to participate the government’s Global Innovation Partnership Program to deepen technology cooperation, a ministry official told the

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the world’s leading advanced chipmaker, officially began volume production of its 2-nanometer chips in the fourth quarter of this year, according to a recent update on the company’s Web site. The low-key announcement confirms that TSMC, the go-to chipmaker for artificial intelligence (AI) hardware providers Nvidia Corp and iPhone maker Apple Inc, met its original roadmap for the next-generation technology. Production is currently centered at Fab 22 in Kaohsiung, utilizing the company’s first-generation nanosheet transistor technology. The new architecture achieves “full-node strides in performance and power consumption,” TSMC said. The company described the 2nm process as

JOINT EFFORTS: MediaTek would partner with Denso to develop custom chips to support the car-part specialist company’s driver-assist systems in an expanding market MediaTek Inc (聯發科), the world’s largest mobile phone chip designer, yesterday said it is working closely with Japan’s Denso Corp to build a custom automotive system-on-chip (SoC) solution tailored for advanced driver-assistance systems and cockpit systems, adding another customer to its new application-specific IC (ASIC) business. This effort merges Denso’s automotive-grade safety expertise and deep vehicle integration with MediaTek’s technologies cultivated through the development of Media- Tek’s Dimensity AX, leveraging efficient, high-performance SoCs and artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities to offer a scalable, production-ready platform for next-generation driver assistance, the company said in a statement yesterday. “Through this collaboration, we are bringing two