The Hajar Mountains reach nearly 3,000m above sea level, tracing the coastline of Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Their arid peaks and valleys might seem desolate, but they could hold one of the keys to slowing global warming.

The range is home to one of the world’s largest deposits of olivine, a green mineral that a start-up wants to extract, grind up and scatter along shorelines to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The world would need to remove billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide directly from the air each year by the middle of the century to avert the worst effects of climate change. A growing number of start-ups are attempting to do so, using techniques that range from carbon-capturing machines to sequestering bio-oil underground. Some are turning to the ocean — which already absorbs about one-quarter of all carbon emissions — as a potential solution, including San Francisco-based Vesta.

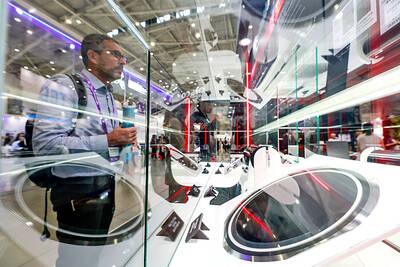

Photo: Bloomberg

The firm wants to dump ground-up olivine on beaches and into seawater in an attempt to speed up the ocean’s natural ability to remove carbon dioxide. As the olivine dissolves in seawater, a chemical reaction occurs that pulls carbon from the air and eventually locks it up in the ocean in dissolved bicarbonate form. It is one of a number of techniques known as enhanced rock weathering that start-ups are testing on land and at sea.

Vesta has tested its technology on a beach in New York’s Hamptons, spreading olivine on the coast and mixing it with sand. The start-up has set its sights further afield for its next project, believing that the Middle East might offer the best shot at capturing carbon dioxide cheaply and at scale.

“What we’re looking for is locations which have large amounts of the mineral and the right oceanographic conditions,” Vesta chief executive officer Tom Green said. “When you look at the Middle East, you have both.”

It takes about 1 tonne of olivine to remove 1 tonne of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, making securing access to a huge amount of the mineral critical to Vesta’s efforts, Green said.

Vesta’s solution has the potential to remove 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by midcentury, in part because olivine is one of the world’s most abundant minerals, he said.

In his view, extracting the billion tonnes of olivine needed to reach that ambition “is large, but feasible” given the scale of comparative mining industries such as coal and limestone aggregate.

Vesta’s analysis has identified the Persian Gulf as an ideal location to deploy its technology due to the chemistry and high temperature of the waters as well as the types of currents, Green said.

The waters of the Gulf are some of the warmest in the world, for example, which could make Vesta’s carbon removal process more efficient.

The deposits of olivine in the Hajar Mountains and established mining companies in Oman and the UAE could prove a boon to Vesta, Green said.

The region is also no stranger to large-scale coastal projects, including the construction of islands. (Some of those projects have garnered criticism from environmental groups for damaging biodiversity and eroding the shoreline.)

“The equipment being used for that is the same and the techniques are similar to the work that we do,” Green said.

Although he declined to name specific olivine suppliers and purchasers, he said that the start-up plans to deploy olivine in the region within the next two years.

The UAE is a major proponent of carbon capture technologies as a solution to the climate crisis in part because it would allow the country to continue to pump oil and gas, the mainstay of its economy. State energy firm Abu Dhabi National Oil Co (ADNOC) is working on a US$900 million project to build more than 40 million barrels of oil storage in caverns in the same stretch of mountains that could supply massive amounts of olivine.

“There’s clearly a desire to invest in carbon removal programs,” Green said of the UAE. “We had multiple potential stakeholders ask us: ‘How quickly can you scale this?’”

UAE officials are expected to vigorously push carbon capture as a climate solution at the UN COP28 summit starting next month, which Dubai is to host.

COP28 president Sultan al-Jaber — who also heads ADNOC — has said that climate diplomacy should focus on phasing out emissions from oil and gas, leaving the door open for the continued use of fossil fuels coupled with carbon sequestration.

The stance is at odds with EU and US diplomats as well as the best available science, which shows the need to wind down the use of fossil fuels in the coming decades to avert catastrophic damage to the climate. While the world would likely need to remove billions of tonnes of carbon from the air in the coming decades, research indicates that those efforts should be focused on intractable emissions from sources such as heavy industry and aviation.

Two major hurdles the carbon removal industry faces are high costs and energy use. Techniques to remove carbon from the atmosphere run into the hundreds or even thousands of dollars per tonne.

Vesta says its approach could cost as little as US$21 and require 40 kilowatt-hours of energy to remove 1 tonne of carbon dioxide, although Green declined to say the current cost of Vesta’s services.

A 2022 report released last year by the National Academy of Sciences estimated that the likely cost to deploy this and similar techniques in the coming decades ranges from US$100 to US$150 per tonne of carbon dioxide.

There are also a number of other issues with seeding the ocean with olivine, including questions over how much the mineral can speed up carbon sequestration.

Peter Kelemen, a professor of geochemistry at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said that the process of olivine dissolution has a half-life of about 70 years, meaning that it would take 70 years for half of the olivine deposited to dissolve and remove carbon dioxide in the process.

“The uncertainties are big,” he added.

For its part, Vesta says it is targeting a half-life of about 10 to 20 years, owing to high water temperatures, wave action and how finely the olivine sand is ground.

Taking accurate measurements of how much carbon has been removed from the atmosphere is also a challenge. Vesta has deployed custom hardware on the seabed of its Hamptons pilot site that measures variables such as alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon, which it says allow it to model how much carbon was removed.

“With a rock, especially when it’s so dispersed over a beach, you have no idea how quickly this stuff is dissolving,” said David Ho, a professor in the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s oceanography department.

The effects on ecosystems of lacing coastlines with olivine is also largely unknown. Organisms that live in the sand could find it challenging to live in that kind of environment, and olivine often contains toxic metals such as nickel and chromium.

If the olivine is ground very fine, its presence could affect small critters at the bottom of the food chain by blocking light, said Kate Moran, chief executive officer and president of Ocean Networks Canada, an organization that monitors ocean health.

That could ripple upward, having unintended consequences.

In addition, measuring the ecological effect of making the ocean more alkaline is “challenging,” she said.

Still, Green says the seas are a key avenue to put the brakes on global warming.

“Because we’re sort of terrestrial creatures, we have a terrestrial bias,” he said. “But, actually, the ocean presents the largest potential opportunity for carbon removal.”

SEMICONDUCTORS: The German laser and plasma generator company will expand its local services as its specialized offerings support Taiwan’s semiconductor industries Trumpf SE + Co KG, a global leader in supplying laser technology and plasma generators used in chip production, is expanding its investments in Taiwan in an effort to deeply integrate into the global semiconductor supply chain in the pursuit of growth. The company, headquartered in Ditzingen, Germany, has invested significantly in a newly inaugurated regional technical center for plasma generators in Taoyuan, its latest expansion in Taiwan after being engaged in various industries for more than 25 years. The center, the first of its kind Trumpf built outside Germany, aims to serve customers from Taiwan, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Korea,

Gasoline and diesel prices at domestic fuel stations are to fall NT$0.2 per liter this week, down for a second consecutive week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) announced yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to drop to NT$26.4, NT$27.9 and NT$29.9 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, the companies said in separate statements. The price of premium diesel is to fall to NT$24.8 per liter at CPC stations and NT$24.6 at Formosa pumps, they said. The price adjustments came even as international crude oil prices rose last week, as traders

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), which supplies advanced chips to Nvidia Corp and Apple Inc, yesterday reported NT$1.046 trillion (US$33.1 billion) in revenue for last quarter, driven by constantly strong demand for artificial intelligence (AI) chips, falling in the upper end of its forecast. Based on TSMC’s financial guidance, revenue would expand about 22 percent sequentially to the range from US$32.2 billion to US$33.4 billion during the final quarter of 2024, it told investors in October last year. Last year in total, revenue jumped 31.61 percent to NT$3.81 trillion, compared with NT$2.89 trillion generated in the year before, according to

SIZE MATTERS: TSMC started phasing out 8-inch wafer production last year, while Samsung is more aggressively retiring 8-inch capacity, TrendForce said Chipmakers are expected to raise prices of 8-inch wafers by up to 20 percent this year on concern over supply constraints as major contract chipmakers Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and Samsung Electronics Co gradually retire less advanced wafer capacity, TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. It is the first significant across-the-board price hike since a global semiconductor correction in 2023, the Taipei-based market researcher said in a report. Global 8-inch wafer capacity slid 0.3 percent year-on-year last year, although 8-inch wafer prices still hovered at relatively stable levels throughout the year, TrendForce said. The downward trend is expected to continue this year,