Tucked away in the rolling hills of Iraqi Kurdistan is a hidden treasure: tens of thousands of olive trees, thriving in a new homeland after being smuggled from neighboring Syria.

Their branches are heaving with bright purple-black olives ready to be picked.

Their caretaker, Syrian Kurdish businessman Suleiman Sheikho, is proud to have brought the olive oil business to Iraq’s autonomous north.

Photo: AFP

“This year was a good year,” said 58-year-old Sheikho, who has been transporting trees from his native Afrin in northwest Syria into Kurdish Iraq since 2007.

“On this farm I have 42,000 olive trees, all of which I brought from Afrin when they were three years old,” he said, gesturing to neat rows reaching the horizon.

In early 2018, his mission took on a new urgency.

Turkey, which saw the semi-autonomous Kurdish zone of Afrin on its border as a threat, backed an offensive by Syrian rebel groups to take control of the canton.

The operation, dubbed “Olive Branch,” displaced tens of thousands, many of whom had made their living for decades by producing olive oil in the area’s mild climate.

Sheikho himself is a fourth-generation olive farmer and had 4,000 trees in Afrin that are older than a century.

The slender businessman, who once served as the head of Afrin Union for Olive Production, sprung into action.

He transported some of his trees legally, but smuggled others across the border, managed on both sides by autonomous Kurdish authorities.

Some of the new transplants joined his orchard, located among luxurious summer villas near the regional capital, Erbil. He sold others to farmers across Kurdish Iraq.

Raw olives are a staple on Levantine lunch tables, while their oil is used in cooking and drizzled on top of favorite appetizers such as hummus. The oil can also be used to make soap, while the dark, sawdust-like residue from olives pressed in the autumn is often burned to heat houses in winter.

Olive trees struggle in the blistering heat and desert landscapes of Iraq, so the yellowish-green oil was long imported at great expense from Lebanon, Syria or Turkey.

A domestic oil industry could change all that. Sheikho was relieved to find the soil near Erbil as rich as in his hometown, but the warmer temperatures meant his trees required more robust irrigation networks.

There are two harvests a year, in February and November. He built a press, where the olives are separated from twigs and leaves, pitted, then squeezed to produce thick, aromatic oil.

Dressed in a charcoal gray blazer during a visit by Agence France-Presse, Sheikho tested the quality by drinking it raw from the press, before the viscous fluid was poured into plastic jugs.

“For every 100 kilos of olives, I produced 23 kilos of olive oil,” he said.

Olive oil production had not taken root when Sheikho began working in Erbil, but has thrived since Syrians displaced by their country’s nearly decade-long war began moving there.

According to the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources, there were just more than 169,000 olive trees in the Kurdish region in 2008.

Since then, the ministry invested about US$23 million in planting and importing the trees, which now number about 4 million, it said.

There are around a half-dozen olive presses, employing many Syrian Kurds from Afrin.

Sheikho sees more fertile ground ahead.

“The farmers here have great ideas, and they are extremely ambitious,” he said. “With the hard work and experience of Afrin’s farmers, they are going to create a very bright future for olive business.”

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

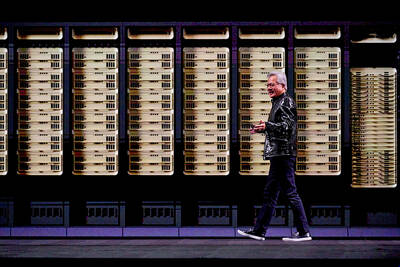

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,