It might have all been different had former US president John F. Kennedy not been assassinated. Or so the local legend goes.

Before fate intervened, the native Bostonian planned to root the US space program in Cambridge, Massachusetts. An 11.7-hectare site in Kendall Square was vacated to be the home of the electronics center of NASA.

However, by the late 1960s, after Kennedy was shot, the agency’s plans changed.

“Houston, we have a problem” entered the lexicon, while much of the Cambridge neighborhood fell into disrepair.

A half-century later, the area is among the most expensive business districts in the US.

The story of how office space in a blue-collar Boston suburb came to command rents comparable to the priciest pockets of Manhattan or San Francisco is also a story of scientific ambitions that match Kennedy’s 1961 vow to reach the moon.

The next great frontier, investors in Cambridge-area firms are betting, would be unlocking ever-deeper mysteries of life to develop unprecedented therapies.

Much of that work is being done in Kendall Square, by companies and academic centers that are often on the same block — even in the same building.

Sixty-two public companies with a combined market value of about US$170 billion, the majority of them biotechnology firms, call Cambridge home.

Global pharmaceutical giants, including Takeda Pharmaceutical Co, Sanofi SA and Novartis AG, also have extensive research operations in the city.

“Perhaps the best way to explain Kendall Square to the people beyond the world of science and the world of Massachusetts area is this: Kendall Square is to science what New York is to finance, what Paris is to culture, what Washington is to government,” said Jay Bradner, president of the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, the research hub of the Swiss giant located across the street from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) museum.

The sense of being at a historical crossroads has meant that Cambridge competes with midtown Manhattan as the priciest commercial real-estate market in the US.

Average office rents in the third quarter of this year were US$82.23 a square foot (0.1m2), according to commercial real-estate firm CBRE Group Inc, just a hair behind US$82.51 a square foot in midtown Manhattan.

Main Street, home to academic centers that contributed to the Human Genome Project and early Crispr research, is the fourth-most-expensive commercial thoroughfare in the US, trailing only Silicon Valley’s Sand Hill Road, Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue and San Francisco’s Mission Street.

While it might seem inevitable that the area around MIT would become exceedingly valuable, for much of its history Kendall Square was a dump.

Locals recall empty parking lots and bad architecture. Rents were relatively low, which made it easy for biotech pioneers, such as Biogen Inc, to grow and flourish.

That soon changed. Joel Marcus, chairman and co-founder of Alexandria Real Estate Equities Inc, was one of the driving forces of the transformation.

Marcus is an unlikely baron of Kendall Square. He has never developed a drug. He does not have a doctorate degree. He does not live in Cambridge, or even on the East Coast.

Instead, Marcus, who resides in Pasadena, California, trained as an accountant and became a lawyer for drugmakers.

In 1994, Marcus realized that the biotechnology companies he was representing in California needed laboratory space and wanted to be near major academic facilities.

He and his partners started a real-estate development company to build labs. Anticipating the growth of the industry turned Alexandria’s initial US$19 million investment into an empire now worth US$13 billion.

“Our thesis has always been the biology revolution is really in the very early days, and very early stages,” he said. “There are 10,000 diseases known to mankind today, only 500 of which have been addressed in some fashion, whether it be treatments or cures.”

Alexandria, Virginia, was evolving at the same time that a landmark piece of economic research would change the way people think about where companies locate.

The work of Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter explores a paradox of the post-Internet economy: If business can be done from anywhere, why do so many companies clump together in the same place?

In a 1998 paper, titled “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition,” Porter theorized about why companies in the same industry were so often neighbors.

He called these ecosystems clusters and held up Northern California’s winemakers and Italy’s luxury fashion houses as examples.

Porter found that clustered businesses were more productive and innovative. Clusters led to the creation of more businesses.

According to Porter, the larger ecosystem acts as a sort of mega-corporation: Individual companies benefit as if they were part of a larger organization, gaining access to suppliers, talent and capital while maintaining their independence.

Marcus built on the idea. Alexandria’s application of clustering first took firm root in the San Francisco Bay Area, which the company entered in 1999.

That year, an Internet start-up asked about renting space in a three-building laboratory complex in Mountain View. Alexandria was reluctant. It could charge US$6 a square foot for lab tenants, while office space went for about half that.

The start-up said it would pay the higher rent, even though it planned to rip out the labs.

“We didn’t know what Google was, I’d never heard of it. I had no ability to google Google and find out what it was,” Marcus said.

After checking with the start-up’s backers, Marcus decided to take a risk and rent to it.

Through a venture arm, Alexandria also put money into then-private Google, an investment that remains the fund’s best ever.

Pairing tech and lab tenants turned out to be a winning combination.

Today, Alexandria owns 585,289m2 in the greater San Francisco area, where its tenants include Facebook Inc and Uber Technologies Inc, as well as storied biotech Genentech, owned by Roche Holding AG, and Nektar Therapeutics Inc.

However, even as rents rise in San Francisco, Alexandria makes more money in Cambridge.

In the early 2000s, although Alexandria had the bulk of its holdings in California, something back east caught Marcus’s attention. Novartis, the Swiss pharmaceutical giant, said it planned to move its research headquarters to Kendall Square.

Alexandria wagered that the Cambridge market would heat up if other global pharmaceutical players were to follow.

In 2002, it bought its first building on the outer reaches of the neighborhood, along Memorial Drive, the highway that snakes along the Charles River.

Then it snapped up a seven-building parcel called Technology Square from MIT for US$600 million in 2006. Alexandria converted two of the buildings from office to lab space, doubling the rent.

It was substantially leased before the conversion was finished and was completely leased shortly thereafter.

Seeing that success, the company bet that if it created a biotechnology campus from the ground up, it could attract further tenants.

From 2006 to 2008, it assembled about a dozen parcels along Binney Street, a trucking route near NASA’s old would-be site.

Despite souring real-estate market conditions, Alexandria kept buying and building into the recession.

Today, Alexandria’s Binney Street corridor houses Sanofi, IBM Watson, Bluebird Bio Inc, Biogen, Sarepta Therapeutics Inc, Sage Therapeutics Inc, Relay Therapeutics and Constellation Pharmaceuticals Inc.

“We started just with a business plan, a financial model and kind of a hope that our US$19 million that we raised from — you know — friends and family would someday, maybe create a little company that could own a few buildings,” Marcus said. “We never quite imagined what it is today.”

IN THE AIR: While most companies said they were committed to North American operations, some added that production and costs would depend on the outcome of a US trade probe Leading local contract electronics makers Wistron Corp (緯創), Quanta Computer Inc (廣達), Inventec Corp (英業達) and Compal Electronics Inc (仁寶) are to maintain their North American expansion plans, despite Washington’s 20 percent tariff on Taiwanese goods. Wistron said it has long maintained a presence in the US, while distributing production across Taiwan, North America, Southeast Asia and Europe. The company is in talks with customers to align capacity with their site preferences, a company official told the Taipei Times by telephone on Friday. The company is still in talks with clients over who would bear the tariff costs, with the outcome pending further

A proposed 100 percent tariff on chip imports announced by US President Donald Trump could shift more of Taiwan’s semiconductor production overseas, a Taiwan Institute of Economic Research (TIER) researcher said yesterday. Trump’s tariff policy will accelerate the global semiconductor industry’s pace to establish roots in the US, leading to higher supply chain costs and ultimately raising prices of consumer electronics and creating uncertainty for future market demand, Arisa Liu (劉佩真) at the institute’s Taiwan Industry Economics Database said in a telephone interview. Trump’s move signals his intention to "restore the glory of the US semiconductor industry," Liu noted, saying that

STILL UNCLEAR: Several aspects of the policy still need to be clarified, such as whether the exemptions would expand to related products, PwC Taiwan warned The TAIEX surged yesterday, led by gains in Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), after US President Donald Trump announced a sweeping 100 percent tariff on imported semiconductors — while exempting companies operating or building plants in the US, which includes TSMC. The benchmark index jumped 556.41 points, or 2.37 percent, to close at 24,003.77, breaching the 24,000-point level and hitting its highest close this year, Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) data showed. TSMC rose NT$55, or 4.89 percent, to close at a record NT$1,180, as the company is already investing heavily in a multibillion-dollar plant in Arizona that led investors to assume

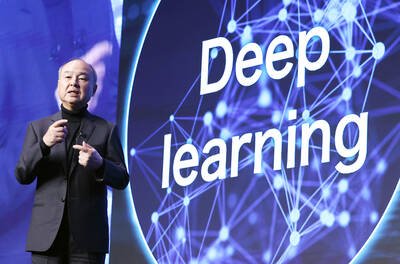

AI: Softbank’s stake increases in Nvidia and TSMC reflect Masayoshi Son’s effort to gain a foothold in key nodes of the AI value chain, from chip design to data infrastructure Softbank Group Corp is building up stakes in Nvidia Corp and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the latest reflection of founder Masayoshi Son’s focus on the tools and hardware underpinning artificial intelligence (AI). The Japanese technology investor raised its stake in Nvidia to about US$3 billion by the end of March, up from US$1 billion in the prior quarter, regulatory filings showed. It bought about US$330 million worth of TSMC shares and US$170 million in Oracle Corp, they showed. Softbank’s signature Vision Fund has also monetized almost US$2 billion of public and private assets in the first half of this year,