Dozens of girls in tiaras and boys in tuxedos who dreamed of becoming China’s next musical sensation stared at the beast onstage. At 2.7m long and more than 450kg, with a steely black sheen and a price of more than US$200,000, the Steinway & Sons D-274 concert grand piano seemed designed to intimidate.

There were whispers that the piano had come from far away, in Germany; that it could kill you in an instant if it rolled off the stage; that it had the power to turn even the sloppiest of scales into material primed for Carnegie Hall.

“It’s flawless, exquisite, with a special sound,” said Li Wei, the mother of an 11-year-old boy who had come to the theater to take part in the final round of the Steinway & Sons International Youth Piano Competition in China last winter.

Photo: AP

“Everyone wants a Steinway,” said Xiao Yunchu, a quiet 13-year-old who favored the pyrotechnics of Hungarian composer Franz Liszt. “But none of us can afford it.”

Steinway, one of the world’s most prestigious musical instrument brands, is looking to China to breathe new life into lackluster sales. To succeed, it will need more than smart marketing. It will need to fine-tune a cultural mindset in a nation that once dismissed pianos as bourgeois luxuries.

Steinway dealers have to convince their wealthier clientele that the instruments make good investments, avoiding the overly aggressive sales tactics that tripped up some early efforts. They have to educate parents about the potential payoff of buying a piano that can cost as much as an apartment. And they need to woo music students who are increasingly turning to lower-cost keyboards and so-called smart pianos, which use lights, iPads and other technical tools to teach basic skills.

The company, known for its painstaking craftsmanship, has grudgingly entered the digital game. The new Steinway Spirio is a high-tech take on the jazz-era player piano, loaded with standard classical fare as well as Chinese tunes, including local pop hits like The Moon Represents My Heart (月亮代表我的心) and compositions like The Yellow River Piano Concerto (黃河協奏曲), a piece that dates to the Cultural Revolution.

Founded in 1853 in a Manhattan loft by a German immigrant, Steinway flourished for generations by selling high-end pianos, each crafted by hand from materials like Sitka spruce and cast iron, in the US and Europe. However, the company has suffered as piano playing wanes in the West. Music schools and concert halls have cut back on orders. Piano stores have closed. In the face of uncertainty about its future, Steinway was sold three years ago to an investment firm owned by hedge fund billionaire John Paulson.

In China, Steinway sees potential in what it calls the “tiger mom” phenomenon — middle-class parents willing to spend small fortunes to produce high-achieving children with musical talent. By some estimates, the country has as many as 40 million piano students, compared with 6 million in the US.

MARQUEE EVENT

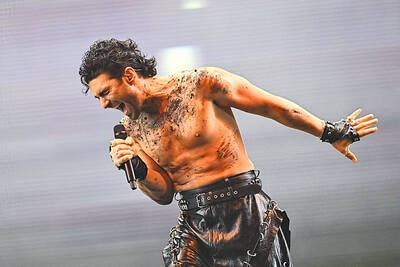

“In America, you’ve already had the piano for hundreds of years,” said Lang Lang (郎朗), a classical pianist with a rock star flair who is one of China’s most prominent musicians. “In China, it’s fresher, it’s newer. Everyone wants to play.”

For Steinway, China has proved to be a shot in the arm. Sales increased more than 15 percent a year over the past decade, far outpacing the single-digit growth of the US and Europe. China is now Steinway’s largest market for pianos outside the US, representing about one-third of global sales. In a sign of China’s importance, the company next year will unveil a 5,574m2 headquarters for Asia in Shanghai, complete with a recital hall.

The youth piano competition in the city of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, from Dec. 10 to 13, the seventh of its kind on the mainland, was the marquee event of the year, a chance to imprint the Steinway lore in the minds of thousands of students, parents and teachers. Students ages 6 to 16 came from across China to Ningbo, a Silk Road trading port three hours south of Shanghai, to compete for an opportunity to perform in Hamburg, Germany, the birthplace of Brahms and one of Steinway’s main hubs.

Over lunch at a downtown hotel, Steinway executives celebrated the success of the competition, which attracted more than 15,000 applicants, a record. Steinway executives said they dreamed of a day when the company’s pianos filled living rooms across China and the company name was as well known in the country as Gucci. But they acknowledged that if Steinway were to thrive in China, it would need a cultural shift in a country where low-end pianos have dominated the market for decades.

As the competition began in Ningbo and children took to the stage to perform Mozart, Brahms and Gershwin, the president of Steinway’s Asia division, Werner Husmann, said the piano maker would need to establish a new audience in China to survive.

“These people are our customers of the future,” he said. “We need to keep piano playing popular.”

Wherever Husmann went during a trip to China for Steinway in the late 1990s, he saw what he began referring to as PSOs, or piano-shaped objects — instruments that had long ago lost their music-making abilities. Some had uneven legs and drifted toward the audience during performances. Others sat on street corners, rain or shine.

Even so, Husmann came away with a sense that there was a love of Western music in Chinese society and that there would soon be a market for high-quality instruments. When he returned to Hamburg to sell his colleagues on the idea, they laughed.

“The first reaction was more or less that I should see a doctor to do a mental check,” he said. “It was like: ‘What the hell can you do in China?’”

When Steinway opened an office in Shanghai in 2004, most of its sales in China were to music conservatories. It was not until the global financial crisis struck four years later that the importance of the Chinese market became clear.

As the world economy weakened, piano sales in the US and Europe, already in decline, fell sharply. In 1909, 364,000 pianos were sold annually in the US; by 2009, that number had slumped to 30,000, according to the National Association of Music Merchants. Doomsday scenarios predicted the extinction of pianos.

Despite Steinway’s devout following — the company says it is the instrument of choice for 98 percent of the world’s performing pianists, including Billy Joel and Argentine musician Martha Argerich — it was not immune to the slowdown. Shipments of Steinway pianos dropped substantially in 2009, and the company was forced to lay off workers at its factory in Queens, New York.

While sales revived somewhat, the downturn exposed the limits of Steinway’s traditional markets. As they looked to the future, Steinway’s leaders decided to take the firm private, away from the short-term glare of public shareholders focused on quarterly earnings.

In 2013, Steinway was sold for US$512 million to Paulson, and musicians worried he would interfere with Steinway’s painstaking production process to increase revenue. Steinway was making only about 2,000 pianos a year in New York and Hamburg.

However, Paulson, an amateur pianist with four Steinway pianos, did not change the company’s methods, which he believed were crucial to dominating the high-end market. He urged the company to move more aggressively in emerging countries, where a growing middle class was spending heavily on education. Steinway drew up plans for a hybrid acoustic-digital instrument and broadly ramped up production of traditional pianos to meet demand.

DREAM INVESTMENT

His father was skeptical. His mother worried he would drive the family business into turmoil.

However, Nick Liu (劉騁), a 26-year-old heir to a large musical instrument company in eastern China, was determined. He would open a store focused exclusively on selling the brand of pianos he had worshiped during his days as a budding concert pianist.

Shortly after New Year’s Day last year, in a sleepy business complex in Ningbo that housed a wine store and an art gallery, Liu opened a Steinway dealership, the latest addition to his family’s business empire, Tianmu Music (天目).

Liu found the space with the help of Wang Zhaochun (王兆春), a technology executive and one of Steinway’s most enthusiastic Chinese customers, who owned the building.

Wang was an avid fan of sports cars and watches. However, his latest obsession was a red Steinway concert grand piano valued at more than US$300,000, which he showed off to friends in a private salon decorated with fur rugs and bottles of Royal Salute whisky on the building’s ninth floor.

“I wanted to buy something special,” Wang said. “It’s just like a Rolls-Royce.”

In his store on the ground floor, Liu arranged dozens of pianos, polishing them with cloths made of chicken skin to make each look as seductive as possible. He turned an empty wall into a timeline of Steinway history, beginning with a portrait of company founder Henry Steinway, wearing a top hat and holding a cane. He created a mock living room, complete with Steinway-branded teacups and tissue boxes, to help customers visualize high-end pianos in their own homes.

Yet Liu struggled to make a sale.

“It was hell,” he said. “No customers, just three employees in the store and me.”

His sales team, accustomed to using a pushy manner to peddle far cheaper products, had difficulty connecting with elite customers. Liu, a classically trained pianist, felt more comfortable speaking about the musical aspects of the instruments than investment value.

Selling a Steinway in China is a particularly trying task. Unlike sports cars or watches, pianos are not easy to show off. Many older people in China never developed a talent for playing the piano. The instrument was shunned during the Cultural Revolution, and widespread poverty in the ensuing decades made it inaccessible to many Chinese families.

Steinway has depended on salespeople in more than 25 cities to educate and excite its customers. The company has instructed them to play up the potential return on investment of a Steinway — a message that resonates strongly with frugal Chinese families — and to speak at length about the company’s history.

Liu invited families in for concerts. He began courting music teachers and performers. He recruited a Bentley salesman to help market the pianos to affluent customers.

“We had to convince them that pianos should be a noble good, not something people buy from the grocery store,” he said.

STRANGE REQUESTS

By March, Liu had made his first sale, and he was beginning to learn to accommodate the peculiar requests of his clients.

A customer called one morning to say she wanted to buy a grand piano costing more than US$20,000. However, there was a catch: She demanded that it be delivered at 8pm that same day, on the advice of her spiritual master, who had said that time would accord with the laws of feng shui.

Liu scrambled to make it happen.

By December, Liu had sold 50 pianos at his store in Ningbo. In his office, he kept a supply of single-malt whiskey he sometimes used to celebrate milestones. At the end of his first year, it had begun to run low.

In a sleek office tower in the heart of Beijing’s high-tech hub, 60 engineers and 20 musicians work day and night to perfect a product they hope will one day compete with traditional instruments from makers like Steinway.

The device is a smart piano known as the One, and it uses synchronized lights and video games to show children how to play the piano — no teacher required. With a compact design and a price starting at about US$600, it has proved to be popular among Chinese parents; the company sold 85,000 units in two years.

Founded by an engineer with no background in music, the company that produces the One, Xiaoyezi Technology, has not been shy about its ambitions. “Witness the rebirth of the classical piano,” reads one advertisement.

There are now about 300,000 digital pianos in China, about the same number as acoustic pianos. Some forecasts say the total could reach 1 million within five years.

For generations, Steinway has thrived by ignoring competitors claiming to have reinvented the piano. However, the surging popularity of digital pianos like the One, as well as concerns that a slowing Chinese economy could hurt demand, has prompted the company to reconsider.

In Beijing this month, Steinway unveiled a product that executives heralded as one of the most significant innovations in the company’s 163-year history: Spirio, an acoustic piano equipped with a digital brain so that it can play without human intervention.

“When you rule the piano world for 160 years, you can get complacent,” Husmann said. “It can lead to a mentality of, ‘Everyone needs a Steinway anyway.’ Steinway has to be a fighting hero — we have to fight every day for our business.”

Du Ruizhe, a 15-year-old piano student in Beijing, was the model of a next-generation Steinway customer. She grew up revering the Steinway name, associating it with great pianists like Arthur Rubinstein. She practiced five hours a day — six on weekends — and was ecstatic when she learned she had qualified for the Steinway piano competition in Ningbo.

However, at home, she played on a grand piano made by Kawai, a Japanese maker.

Steinway pianos were simply too expensive, she said.

“It feels like Steinway is getting famous,” said the teenager, who plans to become a piano teacher. “But in many people’s eyes it’s still a luxury, and until that changes, it’s not like we’ll be rushing to get it.”

The Eurovision Song Contest has seen a surge in punter interest at the bookmakers, becoming a major betting event, experts said ahead of last night’s giant glamfest in Basel. “Eurovision has quietly become one of the biggest betting events of the year,” said Tomi Huttunen, senior manager of the Online Computer Finland (OCS) betting and casino platform. Betting sites have long been used to gauge which way voters might be leaning ahead of the world’s biggest televised live music event. However, bookmakers highlight a huge increase in engagement in recent years — and this year in particular. “We’ve already passed 2023’s total activity and

BIG BUCKS: Chairman Wei is expected to receive NT$34.12 million on a proposed NT$5 cash dividend plan, while the National Development Fund would get NT$8.27 billion Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the world’s largest contract chipmaker, yesterday announced that its board of directors approved US$15.25 billion in capital appropriations for long-term expansion to meet growing demand. The funds are to be used for installing advanced technology and packaging capacity, expanding mature and specialty technology, and constructing fabs with facility systems, TSMC said in a statement. The board also approved a proposal to distribute a NT$5 cash dividend per share, based on first-quarter earnings per share of NT$13.94, it said. That surpasses the NT$4.50 dividend for the fourth quarter of last year. TSMC has said that while it is eager

‘IMMENSE SWAY’: The top 50 companies, based on market cap, shape everything from technology to consumer trends, advisory firm Visual Capitalist said Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) was ranked the 10th-most valuable company globally this year, market information advisory firm Visual Capitalist said. TSMC sat on a market cap of about US$915 billion as of Monday last week, making it the 10th-most valuable company in the world and No. 1 in Asia, the publisher said in its “50 Most Valuable Companies in the World” list. Visual Capitalist described TSMC as the world’s largest dedicated semiconductor foundry operator that rolls out chips for major tech names such as US consumer electronics brand Apple Inc, and artificial intelligence (AI) chip designers Nvidia Corp and Advanced

Pegatron Corp (和碩), an iPhone assembler for Apple Inc, is to spend NT$5.64 billion (US$186.82 million) to acquire HTC Corp’s (宏達電) factories in Taoyuan and invest NT$578.57 million in its India subsidiary to expand manufacturing capacity, after its board approved the plans on Wednesday. The Taoyuan factories would expand production of consumer electronics, and communication and computing devices, while the India investment would boost production of communications devices and possibly automotive electronics later, a Pegatron official told the Taipei Times by telephone yesterday. Pegatron expects to complete the Taoyuan factory transaction in the third quarter, said the official, who declined to be