It is 6am, but the pickers are already working in Rose Valley, home to Bulgaria’s centuries-old rose oil industry, providing a vital ingredient for the global perfumes industry — and now with EU protection.

“We go out very early as the roses must be picked while there’s still dew on them. Then the yield is highest,” said Totka Hristova, one of an army of workers on the foot of the Balkan Mountains in the damp cool of the early morning.

A couple of hours later and her day’s work is already over. Once the sun rises high over the rows and rows of pink rose bushes, it gets too hot and the precious oil retreats down into the plant’s roots.

Photo: AFP

“We only pick the fully open roses that are most oil-giving; the others we leave for tomorrow,” the pensioner said, her gloved hands deftly plucking and slipping the flowers into a plastic bag around her waist.

Practically all expensive perfumes the world over contain rose oil.

Bulgaria and neighboring Turkey are the world’s largest producers. The temperate climate and alluvial soils provide the ideal conditions for growing the best plant, the Damascus rose, which is originally from Persia.

Photo: AFP

In a labor-intensive and delicate process unchanged since the days of the Ottoman empire in the 17th century, the petals are taken immediately to distilleries, where they are mixed with water and boiled in vast metal vats. The vapors are then condensed and redistilled to separate the oil. However, the process requires vast volumes of petals. A good worker — it can be tough finding enough staff — can gather up to 25 to 30kg each morning, but 3,500kg are needed to produce just one kilo of oil.

Bulgaria’s annual production of about 1,500kg of rose oil requires 5.25 tonnes of petals, grown on 3,800 hectares of plantations, mostly in the valley around the central Bulgarian town of Kazanlak.

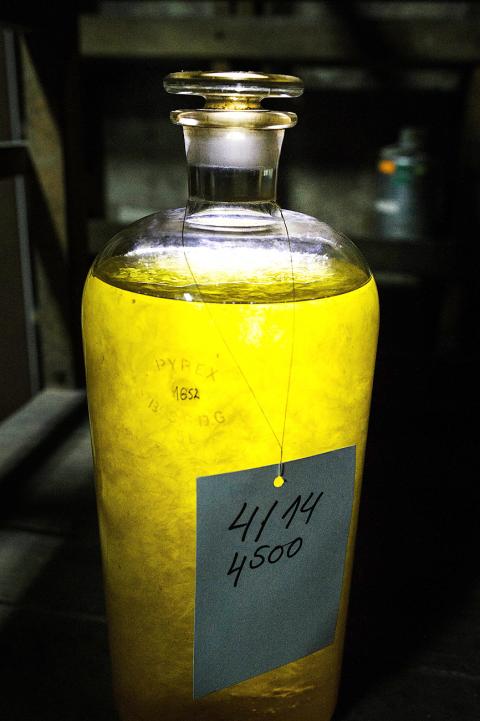

Once this yellowish-green “liquid gold” is packaged into jars ready for sale, it is expensive, selling for 6,000 to 6,500 euros (US$6,700 to US$7,200) and above for a kilo.

Photo: AFP

The buyers — from France, the US and, increasingly, Asia — are generally firms that make intermediary products which they then sell to companies like Christian Dior, Estee Lauder and Chanel.

“If we are talking about expensive perfumes — it’s part of all of them,” said Juliana Ognyanova from Bulattars, a big rose oil exporter.

Surprisingly, the oil — which contains more than 370 components and has no synthetic alternative — is not used for its aroma, which is quite cloying for most noses. Instead it helps combine the huge number of natural and artificial ingredients in perfumes and to increase the amount of time it stays on the skin, said Nikolay Nenov, an expert on rose oil.

Photo: AFP

Because of its high price, rose oil has often been faked — but savvy Bulgarian producers have now found a way to guarantee its authenticity.

In October last year, after a nine-year application process, producers managed to get the name “Bulgarian Rose Oil” registered on the list of EU products of protected geographical indication and designation of origin.

Similar EU certification has already been awarded to products such as Roquefort cheese from France or Melton Mowbray Pork Pies from England.

“This is a huge success for the whole sector,” said Filip Lissicharov, a Bulgarian distillery owner and one of the people behind the registration.

To be granted the certification, producers must prove their flowers come from a traditional rose-growing region in Bulgaria, that they observe strictly the distillation process and that their product has the essential chemical and physical characteristics specific only to Bulgarian rose oil.

Distillers expect a good year even if not a repeat of the bumper harvest from last year, which was the best in the past 20 years.

“The quality of the rose petals is good and we expect that the quality of the rose oil this year will be equally high,” Lissicharov said.

JITTERS: Nexperia has a 20 percent market share for chips powering simpler features such as window controls, and changing supply chains could take years European carmakers are looking into ways to scratch components made with parts from China, spooked by deepening geopolitical spats playing out through chipmaker Nexperia BV and Beijing’s export controls on rare earths. To protect operations from trade ructions, several automakers are pushing major suppliers to find permanent alternatives to Chinese semiconductors, people familiar with the matter said. The industry is considering broader changes to its supply chain to adapt to shifting geopolitics, Europe’s main suppliers lobby CLEPA head Matthias Zink said. “We had some indications already — questions like: ‘How can you supply me without this dependency on China?’” Zink, who also

The number of Taiwanese working in the US rose to a record high of 137,000 last year, driven largely by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) rapid overseas expansion, according to government data released yesterday. A total of 666,000 Taiwanese nationals were employed abroad last year, an increase of 45,000 from 2023 and the highest level since the COVID-19 pandemic, data from the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) showed. Overseas employment had steadily increased between 2009 and 2019, peaking at 739,000, before plunging to 319,000 in 2021 amid US-China trade tensions, global supply chain shifts, reshoring by Taiwanese companies and

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) received about NT$147 billion (US$4.71 billion) in subsidies from the US, Japanese, German and Chinese governments over the past two years for its global expansion. Financial data compiled by the world’s largest contract chipmaker showed the company secured NT$4.77 billion in subsidies from the governments in the third quarter, bringing the total for the first three quarters of the year to about NT$71.9 billion. Along with the NT$75.16 billion in financial aid TSMC received last year, the chipmaker obtained NT$147 billion in subsidies in almost two years, the data showed. The subsidies received by its subsidiaries —

At least US$50 million for the freedom of an Emirati sheikh: That is the king’s ransom paid two weeks ago to militants linked to al-Qaeda who are pushing to topple the Malian government and impose Islamic law. Alongside a crippling fuel blockade, the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) has made kidnapping wealthy foreigners for a ransom a pillar of its strategy of “economic jihad.” Its goal: Oust the junta, which has struggled to contain Mali’s decade-long insurgency since taking power following back-to-back coups in 2020 and 2021, by scaring away investors and paralyzing the west African country’s economy.