Andrew S. Fastow, the former chief financial officer of Enron, was charged on Wednesday with engaging in a vast scheme to use off-the-books partnerships to fraudulently disguise the company's financial performance while enriching himself with millions of dollars in Enron's cash.

The charges -- including fraud, money laundering and conspiracy -- portray Enron as a company where fraud and deceit were the workaday mechanisms used to disguise the failings of a corporation secretly spinning out of control.

Allegations in the government's complaint implicate other executives and financial institutions -- notably Merrill Lynch & Co -- as having direct involvement in criminal activities, or at least knowledge of improper acts.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Fastow, 40, surrendered early this morning to FBI agents. He was then led in handcuffs to the federal courthouse, where a hearing was held to set the terms of his release. Magistrate Judge Martha Crone ordered Fastow to be released on US$5 million bond, secured by a US$3 million investment account and several homes, including that of his parents. Fastow and his wife surrendered their passports, and he agreed to the freezing of US$11 million in other cash. The complaint contends that Enron's chief accounting officer entered into an illegal agreement guaranteeing that the company would shield a partnership controlled by Fastow from losses in its dealings with Enron. The complaint does not name the executive, but the person who held that position was Richard Causey, whom Enron fired last February.

Without identifying Merrill Lynch, the complaint describes what it calls a "sham transaction" involving power barges moored off the Nigerian coast in which a financial institution helped Enron to improperly inflate its earnings. The deal was the subject of a Senate hearing in July.

The details in the complaint provide a strong signal that the government's continuing investigation will focus on the actions of Causey and Merrill Lynch, since both are described as direct participants in acts that prosecutors say were an illegal conspiracy. In a statement, Merrill disputed the allegations in the complaint, saying the transaction it conducted with Enron was legitimate; a lawyer for Causey did not return phone calls.

The complaint also suggests that Enron's longtime chairman and chief executive, Kenneth Lay, may have approved a partnership deal that now is central to the criminal case.

According to the complaint, Causey told a lawyer for Credit Suisse First Boston, another big Wall Street bank, in March 2000 that Enron's chief executive -- at that time Lay -- knew about and approved a partnership through which prosecutors say Fastow and others illegally pocketed millions in corporate cash.

The complaint gives no indication if the government believes Causey's account. A lawyer for Lay denied on Wednesday that his client knew anything about the arrangement, known as Southampton. Reid Weingarten, a lawyer for Causey, did not return telephone calls seeking comment.

While the complaint says that it does not include all of the evidence of criminal activities by Fastow, there appears to be no direct mention of another former Enron chief executive, Jeffrey K. Skilling, as having a connection with the alleged crimes. At one point, the complaint says that "the chief executive" along with others misled Enron's board about the nature of certain partnerships; it is not clear if the reference is to Skilling or Lay.

Outside of court, one of Fastow's lawyers, John W. Keker, said that his client never believed he was committing a crime.

"Andy Fastow welcomes the opportunity to prove the truth about Enron," Keker said. "The truth is simple. Enron hired Andy to arrange off-balance-sheet financing. Enron's board of directors, its CEO and its chairman directed and praised his work. Accountants and lawyers reviewed and approved his work."

The spectacular cascade of corporate collapses over the last year began with Enron's, and Fastow became the most senior former Enron official to join executives of Tyco International, Adelphia Communications, Worldcom and Imclone Systems in facing criminal charges.

Out for justice

"The Enron shareholders and the American public have the right to see justice done in this case," said Andrew Weissmann, an assistant US attorney handling the case for the government's Enron Task Force. "Today we have taken a giant step toward that goal."

In addition to the criminal charges, the Securities and Exchange Commission brought a civil complaint against Fastow here, using the same allegations to accuse him of fraud, misrepresentation and of improperly selling his Enron stock when he knew of the company's financial troubles.

"Apparently Fastow thought he could get away with it," Linda Chatman Thomsen, the deputy enforcement director of the SEC, said at a news conference in Washington. "He was wrong."

The government now has 30 days to obtain a grand jury indictment of Fastow, a deadline that Weissmann said he expects to meet.

As portrayed in the complaint, the illegal conspiracies were of two kinds: schemes in which Fastow defrauded the marketplace by disguising Enron's true financial performance and schemes in which Fastow defrauded Enron itself by siphoning money into his own pockets that rightfully belonged to the company. The crimes were vast and complex, with the proceeds from one illegal transaction at times being used to help finance the next.

According to the complaint, Fastow -- either directly or through co-conspirators -- used fronts to illegally invest his own money in certain partnerships, helped Enron misrepresent its profits through bogus transactions between the company and his partnerships and lied to the company's board of directors.

The government argues that he backdated documents to manipulate the company's financial statements and drained millions of dollars that rightfully belonged to his employer and a bank that invested with it.

To obtain illicit kickbacks, the complaint says, Fastow instructed a colleague to write US$10,000 checks to his wife and children -- an amount intentionally chosen to avoid incurring federal gift taxes.

At the core of the government's complaint is the allegation that Fastow entered into an agreement with Causey under which his primary investment partnership -- known as LJM, the initials of Fastow's wife and children -- would be protected against losses in its dealings with Enron.

According to the complaint, the secret deal was known as the "Global Gallactic" agreement, and it insured that any losses experienced by LJM would be made up later through other deals. Under the law, such an agreement would render sales by Enron to LJM as sham transactions.

In effect, Enron was engaged in a transaction known as "parking," in which a paper trail is created falsely indicating that ownership of an asset has shifted from one entity to another. In this case, Enron shifted assets to LJM for a cash payment it recognized as revenue, only to shift the asset back later on by repurchasing it from LJM at a profit to the partnership. Both Enron and LJM then recorded millions of dollars in profits on deals with no real economic value.

The Nigerian barge transaction involving Merrill Lynch was one such deal, the complaint indicates.

According to the complaint, Enron "sold" the barges to Merrill in December 1999 and recognized the proceeds of the transaction in its financial statements for the year's fourth quarter.

But in truth, according to the complaint, Fastow had a secret agreement with Merrill that the barges would be repurchased in six months, with an assurance that the Wall Street firm would not lose any money. In its own internal records, Merrill referred to the transaction as a "relationship loan" and assumed it would pay "interest" at a rate of 15 percent.

When no new buyer could be found for the barges, the complaint says, LJM purchased the barges one day before the six months ran out. There were no internal valuations conducted to determine a price on the deal, nor any negotiations over price, according to the complaint.

In a statement , Merrill denied that it had allowed the barges to be parked with the firm. "Merrill Lynch's investment was fully at risk in this transaction," the statement says. "Merrill Lynch did not receive any guarantee that Enron or any other entity would purchase our investment."

According to the complaint, Fastow's manipulation of partnerships for his own financial benefit began in early 1997, when he set up two entities collectively known as RADR.

Enron purportedly sold RADR its interest in some wind farms that were about to become less valuable to the company, because of its acquisition of the electric utility in Portland, Ore. The wind farms would retain certain financial benefits, however, if they were sold to an independent partnership.

Not independent

But RADR was not independent of Enron. According to the complaint, Fastow gave a US$419,000 loan to a co-conspirator at Enron, Michael Kopper, who in turn provided the cash to investors -- the so-called Friends of Enron. These people in turn funneled money through Kopper back to Fastow.

Kopper pleaded guilty to two felonies in August and is now a primary witness against Fastow.

Kopper was also a primary participant in a scheme to buy out a California pension fund's US$250 million half-interest in a group of Enron energy properties. Enron wanted to keep the properties off its books, and to accomplish that end accounting rules required an independent investor to own at least three percent of the venture's equity.

Fastow and Kopper set up a partnership called Chewco to buy the pension fund's stake, the complaint says. But in reality only a small sliver of independent equity was provided -- and most of it came from the proceeds of the RADR scheme, the complaint says.

Kopper was named as the manager of Chewco, and was paid fees from the entity. In turn, he kicked back more than US$100,000 in that money to Fastow, who had the authority to authorized more payments to Kopper.

In part because Enron and its auditors finally concluded last November that Chewco was not independent, the company had to restate five years of financial results by hundreds of millions of dollars, a move that precipitated Enron's collapse into bankruptcy.

DIVIDED VIEWS: Although the Fed agreed on holding rates steady, some officials see no rate cuts for this year, while 10 policymakers foresee two or more cuts There are a lot of unknowns about the outlook for the economy and interest rates, but US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled at least one thing seems certain: Higher prices are coming. Fed policymakers voted unanimously to hold interest rates steady at a range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent for a fourth straight meeting on Wednesday, as they await clarity on whether tariffs would leave a one-time or more lasting mark on inflation. Powell said it is still unclear how much of the bill would fall on the shoulders of consumers, but he expects to learn more about tariffs

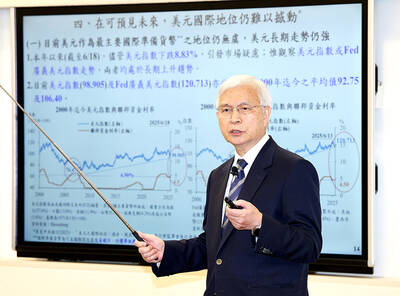

NOT JUSTIFIED: The bank’s governor said there would only be a rate cut if inflation falls below 1.5% and economic conditions deteriorate, which have not been detected The central bank yesterday kept its key interest rates unchanged for a fifth consecutive quarter, aligning with market expectations, while slightly lowering its inflation outlook amid signs of cooling price pressures. The move came after the US Federal Reserve held rates steady overnight, despite pressure from US President Donald Trump to cut borrowing costs. Central bank board members unanimously voted to maintain the discount rate at 2 percent, the secured loan rate at 2.375 percent and the overnight lending rate at 4.25 percent. “We consider the policy decision appropriate, although it suggests tightening leaning after factoring in slackening inflation and stable GDP growth,”

Meta Platforms Inc offered US$100 million bonuses to OpenAI employees in an unsuccessful bid to poach the ChatGPT maker’s talent and strengthen its own generative artificial intelligence (AI) teams, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has said. Facebook’s parent company — a competitor of OpenAI — also offered “giant” annual salaries exceeding US$100 million to OpenAI staffers, Altman said in an interview on the Uncapped with Jack Altman podcast released on Tuesday. “It is crazy,” Sam Altman told his brother Jack in the interview. “I’m really happy that at least so far none of our best people have decided to take them

As they zigzagged from one machine to another in the searing African sun, the workers were covered in black soot. However, the charcoal they were making is known as “green,” and backers hope it can save impoverished Chad from rampant deforestation. Chad, a vast, landlocked country of 19 million people perched at the crossroads of north and central Africa, is steadily turning to desert. It has lost more than 90 percent of its forest cover since the 1970s, hit by climate change and overexploitation of trees for household uses such as cooking, officials say. “Green charcoal” aims to protect what