Gary Winnick knew it was a dinner fit for a king when one showed up. Constantine of Greece was among the 240 luminaries that dined on tournedos of Aberdeen Angus that November evening in 1999 at Claridge's Hotel in London.

The elaborate event, paid for by Global Crossing, the communications company founded by Winnick, included a stirring speech on the role of a late 20th-century superpower by William Cohen, then the US secretary of defense, who had flown 16 hours from Chile to dine with Winnick and his guests.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Celebrated by such figures and buoyed by Global Crossing's soaring stock, Winnick, a recently minted billionaire, seemed to have the world in his palm. Who would have guessed that a kid from Roslyn, New York, would one day rub shoulders with Margaret Thatcher? "One little idea," he once marveled to associates, "and look what's happened to me."

He may no longer want the attention.

In the last month, Global Crossing has collapsed and Winnick -- its chairman -- has troubles aplenty. His reputation has been shattered and his dream of operating a worldwide fiber optic network is in tatters. The fortune he amassed before Global Crossing filed for bankruptcy protection in late January has elicited a chorus of criticism from shareholders who have seen their investments in the company disappear.

The Securities and Exchange Commission and the FBI are investigating Global Crossing's dubious accounting. Employees, investors and corporate governance experts have blasted Winnick's management of the company. "He was the chairman and did not run the company," Winnick's spokesman responded. "The chief executive does."

Others have criticized a style that some associates describe as volatile and arrogant, although Winnick does have some supporters. Stephen Bollenbach, the chief executive of the Hilton Hotels Corp, called Winnick "a good guy." Arnold Kopelson, a Hollywood producer, cited his generosity and his warmth. Others say they have enjoyed working with him.

Still, he has many detractors. Some have criticized a style that associates describe as volatile and arrogant. Others point out that a large chunk of the US$734 million he realized from Global Crossing stock came from share sales that occurred after the company's troubles became clear.

Perhaps no one should have been surprised by his fall. To hear many of Winnick's associates tell it, excess and controversy have periodically played roles in his career since his days at Drexel Burnham Lambert, the failed investment bank famed as the home of Michael Milken.

As head of the convertible bond desk in the Los Angeles office of Drexel, where Milken ruled as the king of junk bonds, Winnick developed a reputation for being condescending and showy. He was the kind of guy who "bragged about his trades," said one co-worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

A spokesman for Winnick denied the portrayal.

Winnick, who is 54, left Drexel in 1985, but controversy followed him. In 1989, he received immunity after agreeing to testify against Milken, who served time in prison for securities and reporting violations. Milken, through his spokesman, declined to comment. A spokesman said Winnick had never testified against Milken.

As his affluence grew, Winnick rarely shied away from self-promotion or ostentatious displays of wealth, former associates say. He owns a palatial estate in the Bel Air section of Los Angeles said to be worth US$94 million. He has a luxurious office in Beverly Hills. His fortune has given him access to several rarefied power circles in Los Angeles and Washington. Both former President George W. Bush and the Democratic fund-raiser Terry McAuliffe reaped small fortunes from Global Crossing stock holdings.

Name dropper

"My new best friend is David Rockefeller," one associate remembers Winnick saying after agreeing two years ago to donate US$5 million to the Museum of Modern Art, where Rockefeller is chairman emeritus.

Before Global Crossing's decline, Winnick showered his beneficence on friends like Lodwrick Cook, the co-chairman of Global Crossing (Winnick's own title is chairman, not co-chairman) and a former chief executive of the Atlantic Richfield Co, who received a Rolls-Royce from Winnick as a personal gift. Even critics say he is extremely charitable.

In August 1998, Global Crossing went public at US$12.75 a share, and in February 2000, just before the Internet bubble burst, Global Crossing stock closed at a high of US$61.8125 a share.

In the interim, not only did Winnick become wealthy, but so did many people close to him, including his housekeeper and a friend, the architect Charles Gwathmey.

If Winnick was impulsively generous to his friends, he was also an impulsive and some say difficult manager, who would call meetings while he worked on his treadmill and routinely dismiss managers.

Lacking experience in operations, he hired and then dismissed four chief executives in four years, offering each of them lucrative signing deals and often giving them lucrative separation agreements. Two former chief executives still have strong ties to Global Crossing. Thomas Casey is a member of its board and John Scanlon is chief executive of Asia Global Crossing, its main subsidiary.

Winnick's personal extravagance set the tone for what several former employees say was undisciplined and reckless spending at Global Crossing. The most obvious outlays went for offices and corporate planes. One former executive recalled that the company leased elegant offices in one of the better office parks in Madison, New Jersey, shortly after Robert Annunziata joined the company. Annunziata, based in New Jersey, did not move to Beverly Hills; he served as chief executive from February 1999 to March 2000.

After Global Crossing paid US$3.4 billion for IXNet in February 2000, IXNet's founder, David Walsh, was named president and then co-chief operating officer of Global Crossing. Even though Global Crossing's stock was beginning its ominous descent, the company undertook an extravagant renovation of its office space at 88 Pine St. in Manhattan.

It installed, for example, a custom-made lighting system to emulate fiber optic strands with neon lighting, one former employee recalled. Several former employees say they thought Walsh had a decorator working almost all the time, redesigning two floors. One recalled that Walsh put in a staircase linking the 29th and 30th floors, then had it changed at a cost the former employee said he believed exceeded US$250,000. A company spokeswoman said the work was started before the purchase of IXNet.

Even last year, as the stock plummeted, the company continued to operate five jets: a Boeing 737, a Challenger, a Gulfstream, an Astra and another plane, a seven-seater. "The company did not need more than one or two planes," one former executive said. Now, according to the spokeswoman, it leases two planes.

A lack of discipline extended beyond offices and planes, according to at least three former Global Crossing employees.

One said the company spent money needlessly for software systems. For example, in early 2000, Global Crossing decided to buy software made by SAP, the German company, for accounting and human resources management, according to a former Global Crossing executive.

This person recalled that several Global Crossing executives were told that it would cost the company at least US$150 million for the systems, and that Global Crossing did not need to buy them because it already had adequate accounting and human resources software.

The company ordered the software anyway, although it was never fully installed, this person said. When installation efforts stalled, Global Crossing's executive vice president for finance, Joseph Perrone, who had been at Arthur Andersen before joining Global Crossing, hired Andersen's consulting division to examine the problem. The company spokeswoman said it had eventually installed the software, but gave no date.

No product profitability measures

One former employee of the Frontier Corp, which Global Crossing acquired in 1999, was surprised to learn after the merger Global never had product profitability measures. They track whether individual products are making money and allow companies to decide whether to continue selling certain products, withdraw them from the market or modify them. At one meeting with Perrone to discuss the importance of such measurements, "he didn't want to put them in," this person recalled. "He said, `They are way too complicated.'"

The company spokeswoman declined to comment.

By the middle of last year, these problems were minor irritations compared with the threat facing Global Crossing -- an overwhelming glut of communications capacity industrywide. So Winnick began a search for investors willing to inject cash into his ailing company.

Winnick found an ally in this search in Steven Green, who had stepped down as US ambassador to Singapore in February 2001. Winnick had met Green nearly 20 years earlier, through Leon Black, another associate from Winnick's days at Drexel.

With Green's help, Winnick cemented contacts with Singapore Technologies Telemedia, a communications company controlled by the Singapore government. Green and Winnick also invested in K1 Ventures, a Singapore-based investment firm controlled by Singapore Technologies' parent company, just as Global Crossing's decline was accelerating last year.

Winnick also lured Hutchison Whampoa, a Hong Kong conglomerate controlled by the billionaire Li Ka-shing, to invest in Global Crossing. Winnick has referred to Li as LK to show how close the two are, a former associate of Winnick said.

By the time Hutchison Whampoa and Singapore Technologies formally agreed to invest in Global Crossing, however, it was too late for Winnick to retain control. They agreed to buy it out of bankruptcy for US$750 million, a fraction of its listed asset value of US$22.5 billion, but the possible success of the bid remained unclear.

Global Crossing's bankruptcy filing wiped out Winnick's own stake in the company, eliminating much of his influence over operations. He is still chairman, but it is unclear whether Global Crossing's new owners will want him to remain connected to the company.

Some investors think this point may be moot if Global Crossing is forced into liquidation and its assets auctioned, a possibility that grows stronger with each day that passes without an offer to rival that of the Asian companies.

SETBACK: Apple’s India iPhone push has been disrupted after Foxconn recalled hundreds of Chinese engineers, amid Beijing’s attempts to curb tech transfers Apple Inc assembly partner Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known internationally as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), has recalled about 300 Chinese engineers from a factory in India, the latest setback for the iPhone maker’s push to rapidly expand in the country. The extraction of Chinese workers from the factory of Yuzhan Technology (India) Private Ltd, a Hon Hai component unit, in southern Tamil Nadu state, is the second such move in a few months. The company has started flying in Taiwanese engineers to replace staff leaving, people familiar with the matter said, asking not to be named, as the

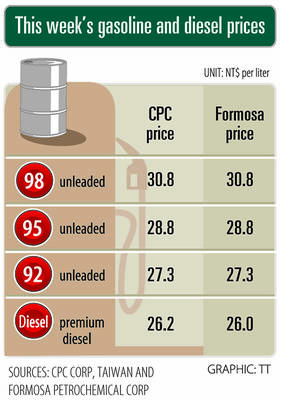

The prices of gasoline and diesel at domestic fuel stations are to rise NT$0.1 and NT$0.4 per liter this week respectively, after international crude oil prices rose last week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) announced yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to rise to NT$27.3, NT$28.8 and NT$30.8 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, the companies said in separate statements. The price of premium diesel is to rise to NT$26.2 per liter at CPC stations and NT$26 at Formosa pumps, they said. The announcements came after international crude oil prices

DOLLAR SIGNS: The central bank rejected claims that the NT dollar had appreciated 10 percentage points more than the yen or the won against the greenback The New Taiwan dollar yesterday fell for a sixth day to its weakest level in three months, driven by equity-related outflows and reactions to an economics official’s exchange rate remarks. The NT dollar slid NT$0.197, or 0.65 percent, to close at NT$30.505 per US dollar, central bank data showed. The local currency has depreciated 1.97 percent so far this month, ranking as the weakest performer among Asian currencies. Dealers attributed the retreat to foreign investors wiring capital gains and dividends abroad after taking profit in local shares. They also pointed to reports that Washington might consider taking equity stakes in chipmakers, including Taiwan Semiconductor

A German company is putting used electric vehicle batteries to new use by stacking them into fridge-size units that homes and businesses can use to store their excess solar and wind energy. This week, the company Voltfang — which means “catching volts” — opened its first industrial site in Aachen, Germany, near the Belgian and Dutch borders. With about 100 staff, Voltfang says it is the biggest facility of its kind in Europe in the budding sector of refurbishing lithium-ion batteries. Its CEO David Oudsandji hopes it would help Europe’s biggest economy ween itself off fossil fuels and increasingly rely on climate-friendly renewables. While