March 2 to March 8

Pan Ying-san (潘英三) recalls seeing Chen Fu-chih’s (陳復志) body in front of the Chiayi Train Station. Chen had been dead for three days, but soldiers forbade his relatives from collecting his body, using the corpse as an example for those who dare oppose the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government.

Five days later on March 23, 1947, the troops executed 11 more people at the same spot. When Pan asked what they did, the troops told him, “these people are hoodlums and bad guys.”

Photos courtesy of Wikimiedia Commons

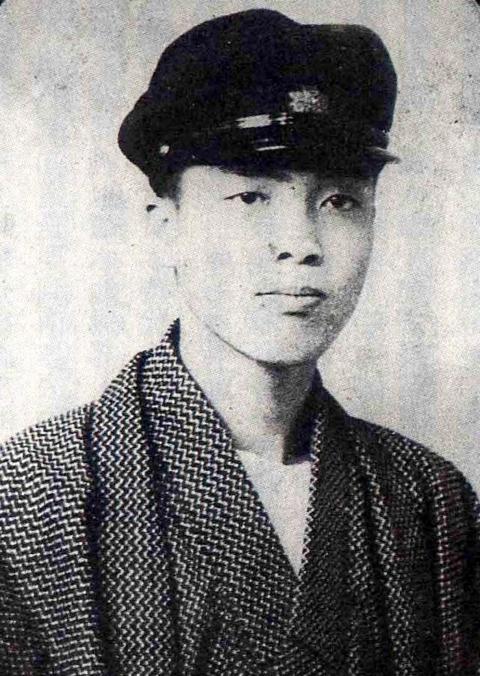

Pan didn’t think that his father Pan Mu-chih (潘木枝) would be among the four men chosen for the next round of public executions two days later. When he rushed to the scene, his father had already been shot, dying in his arms.

These 16 victims made up just a fraction of those who lost their lives when the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed, spread to Chiayi. The civilian militia had the upper hand at first, but government reinforcements soon arrived and began killing or arresting anyone suspected of being involved.

While many of the dead were directly linked to the rebellion, countless more innocent souls lost their lives in the crossfire, became targets of random revenge or were taken away and never heard from again.

Photos courtesy of Wikimiedia Commons

AIRPORT SIEGE

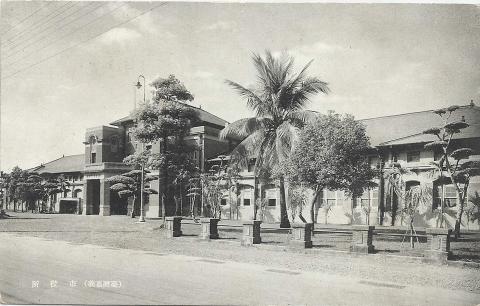

According to Taiwan’s Post-Retrocession Civilian Uprisings: The 32 Incident (台灣光復初期民變: 嘉義三二事變) by historian Hsu Hsueh-chi (許雪姬), the unrest began in Chiayi in the afternoon of March 2, 1947, when dozens of young men arrived from Taichung and Changhua and called for locals to join the fight against the government.

“Are there no heroes in Chiayi?” a man in his 30s with a rifle on his back yelled. “If there is anyone who is truly brave, stand up and come with us to burn the mayor’s dorm!”

Photo courtesy of Wikimiedia Commons

Soon, large groups surrounded then-mayor Sun Chih-chun’s (孫志俊) abode as well as the police station in what Sun would write in his official report as the “Chiayi 32 Incident” (嘉義三二事變). They also reportedly beat up every recent arrival from China they encountered.

Hsu writes that the locals were easily incited after suffering from over a year of corruption in the government and blatant misconduct by KMT soldiers who had arrived from China. Inflation was off the roof, unemployment was on the rise and people were tired of being treated as second-class citizens under the rule of officials sent from China, including Sun.

Minor scuffles had already broken out on March 1, but Sun was somehow convinced that the unrest in the north wouldn’t spread to his city. He managed to get away as his dorm was ransacked; meanwhile a different group stormed the police station and made off with all the firearms. The violence continued into the evening as the group attacked the Monopoly Bureau’s local branch and other residences. By the end of the day, the civilians had control of the city’s transportation, communications and radio station.

Photo courtesy of Wikimiedia Commons

The next day, the citizens formed a committee to deal with the events with Chen as the leader. He was a Taiwanese who fought for the KMT in China against the Japanese, and was chosen because of his experience with both sides. Sun ordered the army into the city the next day, and the fighting renewed. With about 3,000 reinforcements from nearby regions, the civilians were able to besiege Sun and the troops at the Shuishang Airport (水上機場), cutting off the facility’s water and electricity.

Aboriginal Tsou fighters led by Yapasuyongu Yulunana joined the fray on March 7, but they returned to the mountains after the fighters chose to negotiate with the government. Yapasuyongu and several of his comrades were killed by the government in 1954 — but that’s another story.

The besieged troops refused to negotiate with the civilian militia, and with three shipments of artillery from Taipei and two reinforcement battalions arriving, were ready to fight back. The committee sent eight representatives to the airport as a last attempt at talks, but the army detained five of them and began the counterattack.

THE DECEASED

Chen was among the negotiators detained at the airport. On March 18, he was the first to be executed in front of Chiayi Train Station. According to the book In Front of Chiayi Station: 228 (嘉義驛前二二八), 11 civilians met the same fate on March 23, while four Chiayi city councilors were killed on March 25 — among them renowned painter Chen Cheng-po (陳澄波), who was also detained at the airport.

Pan Mu-chih was also one of the negotiators. He was a respected local doctor who allegedly saved Sun’s life by treating his lung disease. Pan was not interested in politics, but he was pushed into the role of negotiator due to his popularity.

And why were some of the others executed? Although neighborhood chief and shoe store owner Wu Hsi-shui (吳溪水) did not participate in the uprising, he was taken away when meeting with other local officials regarding the incident. Others were either marginally involved, held public office or completely innocent.

These 16 were the only ones publicly executed, while countless more lost their lives or disappeared in the weeks of chaos. The book Chulo Mountain Town: 228 (諸羅山城二二八) highlights 29 victims: Cheng Wan-shan (鄭萬山), for example, died fighting government troops, while Chen Tian-tao (陳甜桃) was struck by an artillery shell outside her home and Lin Kuang-chien (林光前) was arrested in the aftermath and never heard from again.

Tsai Chi-tsung (蔡啟聰) was escorting to safety the China-born manager of the sugar factory he worked at when he ran into government troops. In the confusion, the troops killed Tsai and four of his coworkers because they thought he was taking the manager hostage. His relatives never found his body.

The sorrow of those left behind permeate the books, their wounds still not recovered decades after the incident. Chiayi would become the site of Taiwan’s first 228 monument in 1989, the only one to be built in the 1980s.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful