For Westerners writing books about China that aren’t censored there or conceived in a corporate boardroom, there is, says China: Portrait of a People author Tom Carter, a “Holy Trinity of indie publishers” — Earnshaw Books, Blacksmith Books and Taiwan’s Camphor Press.

Arthur Meursault’s Party Members (reviewed in the Taipei Times March 2, 2017) was published by Camphor and was, says Carter, “a big reason why I sought out Camphor Press to publish Bum, and I was deeply honored when they agreed.”

I was initially skeptical about Party Members but have now revised my opinion somewhat. More interestingly, Arthur Meursault is a pseudonym, and some people think the author was actually Carter. This, however, he denies.

The story of An American Bum in China begins in the small town of Muscatine in the US state of Iowa. Muscatine is famous for two things: Mark Twain spent a short time there working as a fledgling local journalist, and that Xi Jinping (習近平) visited twice, first in 1985 as part of a delegation to witness agriculture as practiced in the US, and later in 2012, shortly before he became China’s president.

“You are America,” he commented. Considering that Carter describes the town as “barren of progress, where high unemployment, high industrial pollution, high meth abuse and high teen pregnancies are the norm,” perhaps that was just Xi’s little joke.

My first impression of this book was that it was a novel, albeit a short one. But it soon became obvious that it was more like a memoir written at second-hand.

It’s the story of Matthew Evans, a native of Muscatine, who goes to China to, among other things, lose his virginity. Apparently Evans is a real person and a friend of Carter’s. His attempt to write his own memoir was judged by Carter to be unpublishable, so Evans told Carter to write it himself. An American Bum in China is the result.

We first see Evans scrambling, both ways, through a hole in the wire netting that formed the border between China and Myanmar. He’s to repeat the experience later in the tale. He somehow manages to get to Shanghai where, with the aid of a forged diploma, lands a job as a university professor. His attempts to evade his students’ questions, and instead teach them some very basic English, are hilarious. He’s soon found out, however, and instead of teaching confronts the problems of having “lost” his passport.

He never really recovers from this situation. His family want him to come home to Iowa, but instead he ends up in Hong Kong. It’s 2014 and the start of the Umbrella protests.

Earlier described as a “balding, bespectacled twenty-six-year-old who looked about fifty,” with a pronounced limp, he’s seen in Hong Kong by Carter as “this deranged product of American democracy, singularly embodying everything that had gone wrong with what the protestors were advocating.”

Evans is unimpressed by the Umbrella Movement.

“I mean, Hong Kong needing Beijing’s permission for its elections really isn’t any worse than, y’know, having to get your mother’s permission to go out at night when you’re living at home.”

The protests, however, provide him with an opportunity to pose as an international supporter, sleep in the students’ tents and eat food provided by the movement’s sympathizers. Previous to this he’d been sleeping in cardboard boxes and eating what people had left over at McDonald’s.

My feeling on finishing this book was to wonder what the real-life Matthew Evans would think about it. It’s far from flattering, after all, and the picture is of a natural loser with no redeeming features. That it’s basically true is confirmed by Carter including elements from his own life in the story. He refers, for example, to “my low-budget, thirty-five-thousand mile photographic journey across the thirty-three Chinese provinces between 2006 and 2008.” This is fact, and resulted in Carter’s 2010 book China: Portrait of a People.

In the book, the two men meet from time to time. Carter compares their fortunes as follows: “Evans had bought a fake diploma thinking it would give him a better life, yet I could barely make ends meet with my real degree.”

Asked in an interview what Evans is doing now Carter replies that he has no idea, but expects to hear from him eventually.

Carter is also the editor of Unsavory Elements, a collection of stories by and about the lives of many expats living in China (reviewed in the Taipei Times April 3, 2014). I found this book both entertaining and instructive, and Carter’s contribution especially enjoyable.

I thought An American Bum in China a picaresque foray into the world of the foreign down-and-out reminiscent of the 18th century English novelist Tobias Smollett. Evans is never redeemed, and yet he is in no way mocked, despite numerous opportunities. The book’s title, by the way, derives from the 1981 film An American Werewolf in London.

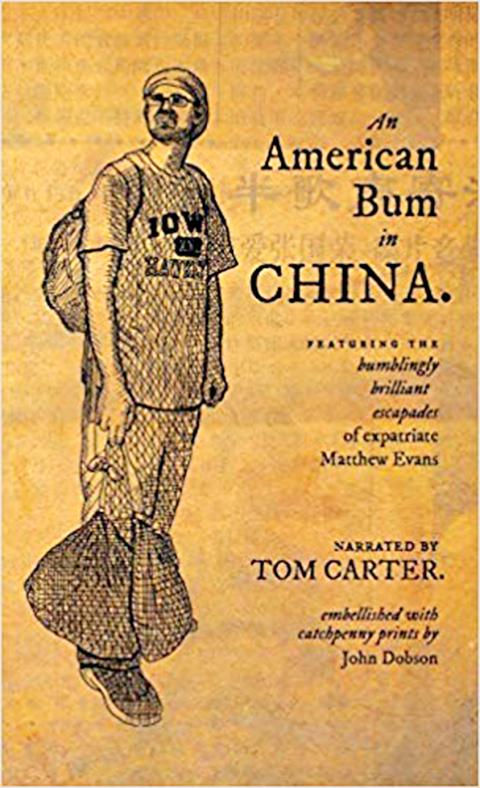

There are in addition a number of line drawings in the book by the artist John Dobson and described on the front cover as “catchpenny prints.”

These add to the impression of the tale’s deliberately light-weight nature, a literary spree about a real-life spree. The whole product, then, acts as enjoyable entertainment eminently fit to while away an otherwise empty afternoon.

Camphor Press now has 90 books to its credit, and must rate as the pre-eminent English-language publisher operating out of Taiwan.

Among Camphor’s 13 titles relating directly to Taiwan are Lord of Formosa by Joyce Bergvelt, The Jing Affair by D.J. Spencer, A Pail of Oysters by Vern Sneider, A Song of Orchid Island by Barry Martinson, Formosan Odyssey by John Grant Ross, The Islands of Taiwan by Richard Saunders, and Barbarian at the Gate by T.C. Locke. All the Camphor books relating to Taiwan, incidentally, are available as a job lot for US$199.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

Fifty-five years ago, a .25-caliber Beretta fired in the revolving door of New York’s Plaza Hotel set Taiwan on an unexpected path to democracy. As Chinese military incursions intensify today, a new documentary, When the Spring Rain Falls (春雨424), revisits that 1970 assassination attempt on then-vice premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Director Sylvia Feng (馮賢賢) raises the question Taiwan faces under existential threat: “How do we safeguard our fragile democracy and precious freedom?” ASSASSINATION After its retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) imposed a ruthless military rule, crushing democratic aspirations and kidnapping dissidents from