April 15 to April 21

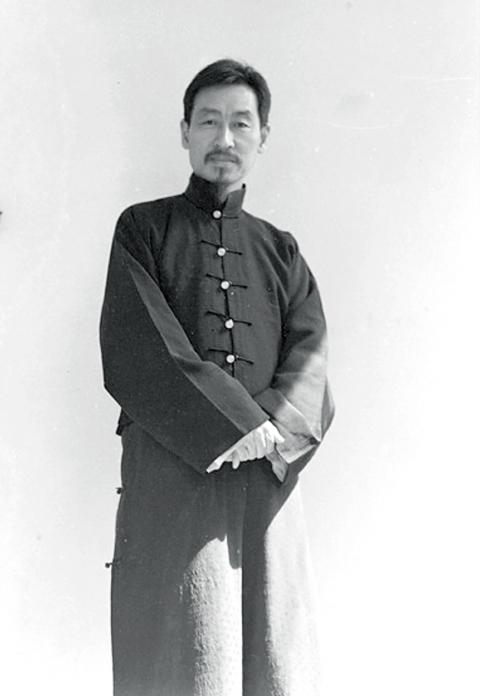

Carrying just 400 negatives and missing most of his equipment, Lang Ching-shan (郎靜山) left Shanghai on the eve of the city’s fall to the Chinese Communists in 1949. His destination was Taiwan, where he was invited by the US Information Agency to put on an exhibition. He would not return home again until 1991.

Often considered the father of Chinese photography, Lang was one of China’s first photojournalists and creator in 1928 of what is believed to be China’s earliest surviving nude. His work was exhibited worldwide and his name is often mentioned among history’s greats.

Photo courtesy of Long Chin-san Art & Cultural Development Association

Lang believed in using Western technology to create a distinct Chinese style that reflected its traditional aesthetics and culture, a style he continued after he was forced to relocate to Taiwan at the end of the Chinese Civil War.

Although he did not produce much new work in his first few years in Taiwan, his status was solid — in 1951, the United Daily News (聯合報) referred to him as a “master photographer.” Much has been written about Lang’s life and work in China, but he also left his mark in Taiwan, active in the art scene up until his death in 1995.

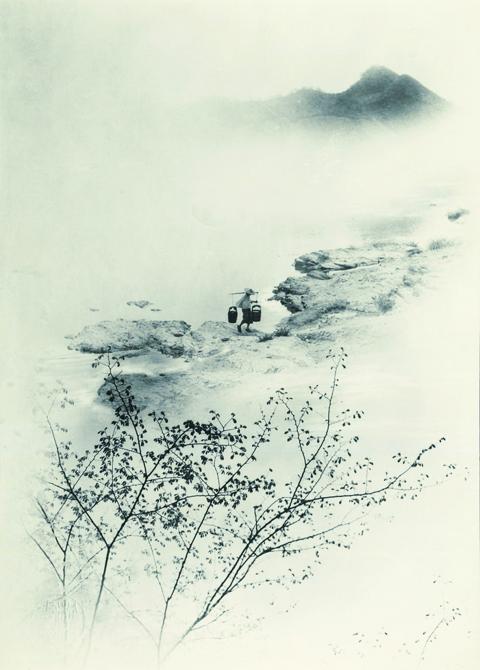

His first official creation in Taiwan, Boating on Misty River, likely reflects his mood toward his situation — it was one of his trademark photo collages stitched together into a Chinese painting-like image using elements from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SHOOTING FORMOSA

Lang may be the father of photography in China, but there was already a small but vibrant community of local photographers when he arrived in Taiwan.

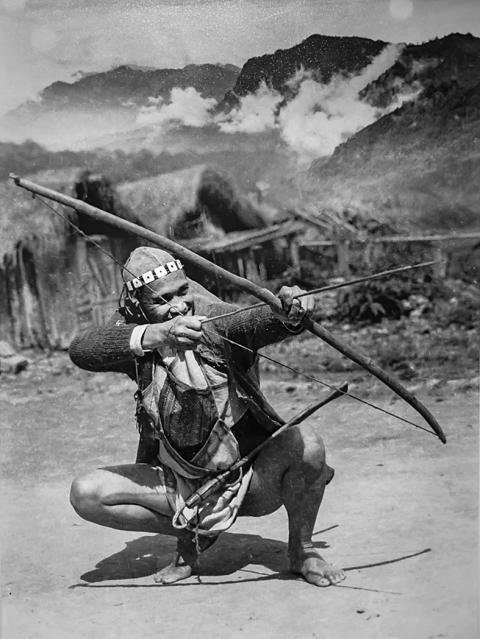

Western visitors brought the first cameras to Taiwan shortly after the invention of photography in 1826, and the oldest known photograph taken in Taiwan, of an Aboriginal couple, was taken around 1850. Before the photo was discovered in 1995 by art professor Wang Ya-lun (王亞倫) at the National Library of France, however, the work of Scottish adventurer John Thomson was probably considered Taiwan’s earliest. Thomson spent about 10 years on and off traveling around Asia from 1862, but his interest in Taiwan wasn’t piqued until 1871 when he met James Maxwell, a fellow Scot and the first Presbyterian missionary to preach on the island. Thomson left behind 40 photographs of his travels in today’s Kaohsiung, Tainan and several Aboriginal villages further up the west coast.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first Taiwanese to learn photography likely acquired their skills through assisting Western missionaries, Chou Wen (周文) writes in the book, Examining National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts’ Collection through the Development of Taiwan’s Photography.

The Japanese brought cameras when they took over Taiwan in 1895, but it was mostly limited to the colonizers’ use for the first decade.

One of the earliest Taiwanese photography pioneers, Deng Nan-guang (鄧南光), developed his passion while studying in Japan in the 1920s. Of course, his family had to be quite wealthy to support his interest. He opened a photography studio after he returned home, and eventually became part of a small but vibrant photography community in the 1940s.

Photo: Lin Liang-sheng, Taipei Times

TAIPEI SALON

Yang Hsin-yi (楊心一) writes in the study Lang Ching-shan and Taiwan that Lang’s work went from subtle, elegant and relaxed during his time in China to something more “elusive, mysterious, foreign, almost like it’s of another realm that one can see but not touch.”

Yang attributes this not only to Lang having to flee his homeland, but also reflecting the Cold War period and martial-law rule. Lang barely escaped trouble in his first year in Taiwan, as the military questioned him for taking photos of Keelung’s harbor and exhibiting them per the city government’s request. The authorities saw Keelung as a strategic site and believed that Lang’s exhibition could reveal sensitive information.

During these years of White Terror, the government greatly restricted creative freedom, and most activities had to fit the bill of promoting Chinese culture and facilitating social cohesion and boosting morale in order to combat communism and reclaim the motherland. Lang cofounded the Chinese Writers’ and Artists’ Association in 1950, and KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) once wrote to Lang, “The arts are a very important spiritual weapon for our people’s fight against the communists and the Russians.”

In a 1967 speech, Lang emphasized the power of art to inspire and mobilize the people, encouraged people to take photographs that reflect positive and healthy ideals and emphasize societal progress and development. Through these images, the government could show the world the advances made in Taiwan in contrast to how China was suffering under communist rule.

Lang actually had little interest in politics, and Liao Hsin-tien (廖新田) writes in the study Lang Ching-shan in Taiwan that he was adept at handling his relationship with the government and saw it more as a means to develop resources and popularize photography in Taiwan. He rarely turned down invitations to serve as guest of honor at countless photography competitions, equipment expos, exhibitions and workshops.

Lang started teaching photography in 1951, and refounded the Photographic Society of China in Taipei in 1953. Later, along with Deng and other Taiwanese photographers, Lang formed the Taipei Photography Salon, which helped popularize the art form and “dictated the direction of Taiwan’s photography from the mid-1950s to the 1960s,” Yang writes. The main idea was using darkroom techniques to create Chinese painting-like images, and this unique style won many international awards and was considered the prestige in Taiwan.

The salon’s great influence relegated other styles to the background, eventually leading to Deng’s departure to found the Photographic Society of Taiwan in 1963 to focus on documentary photography. Younger photographers would later respond with an “anti-salon” movement, putting on a Modern Photography Festival (現代攝影節) in 1966 that pushed the envelope of experimentation.

However, Lang’s work was not limited to the salon as his well-known pieces include that of Taiwan’s cow markets, Aboriginal villages and Double Ten National Day celebrations.

A notable shot taken in Taiwan depicts several Central Cross-Island Highway scenes stitched into a painting-like composition using his trademark collage technique, given to former president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) as a gift. Lang’s value continues to grow as the piece was was auctioned off for NT$3 million in Hong Kong in 2017 — the highest price his work had ever fetched.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South