May 22 to May 28

Chien Chi (簡吉), the “professional peasant revolutionary” featured in last week’s column, was not meant to live a complacent life. In 1947, he was in trouble again for organizing a resistance army to fight Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops during the suppression of the 228 Incident. He went into hiding and worked as a Chinese Communist Party agent until he was caught and executed in 1951.

There would only be a handful of minor and regional farmer protests over the following several decades under the KMT’s reign of White Terror, where dissidents like Chien faced dire consequences. Early land reforms largely eliminated the landowner system, which boosted production but also allowed the state to directly control the farmers. Wu Yen-chang writes in The Formation and Development of Taiwan’s Farmers’ Movement (台灣農民運動的形成與發展) that farmers were organized under state-funded farmers associations, which “operated according to the benefit of the country instead of the agriculture industry and individual farmers.”

Photo: Huang Shu-li, Taipei Times

DISCONTENT BOILS OVER

Martial law would not be lifted until 1987, but as state control loosened, various social movements took shape in the early 1980s, championing issues ranging from pollution to women’s rights to student government elections. Wu writes that these activities encouraged the farmers to speak out as well. He adds that non-KMT politicians, such as Chu Kao-cheng (朱高正), often sought to broaden their voting base by taking up farmers’ issues.

Taiwan’s farmers were hit hard by natural disasters in 1986, which Wu writes was the worst in more than two decades. To make matters worse, farmers began noticing that their fruit prices were plummeting. In an interview with Reading Taiwan magazine, (重現台灣史) opposition politician Lin Feng-hsi (林豐喜) says that nobody could figure out why until they saw that fruit stands were selling mostly imported fruit.

Photo: Lin Kuo-hsien, Taipei Times

Under Lin’s lead, more than 3,000 farmers gathered in front of the Legislative Yuan on Dec. 8, 1987 to protest the increase in imports. The government put together a task force and met with the farmers, where they presented their requests. Five months later, about 500 people rode their farming vehicles on the streets of Taipei during trade talks between the US and Taiwan, protesting the proposed importing of turkey meat. Lin put together a call for farmers insurance as well.

DRAWING BLOOD

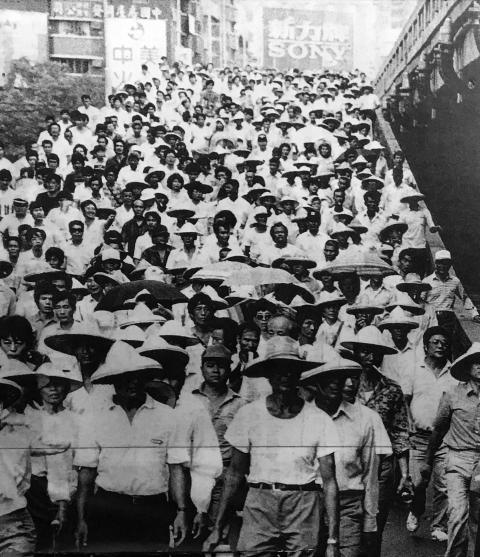

Lin says that he was against taking to the streets so on May 20, 1988, but other activists went ahead with the plan. Spearheaded by the Yunlin Farmers Association (雲林農權會) and future legislators Lin Kuo-hua (林國華) and Hsiao Yu-chen (蕭裕珍), thousands of farmers from across the country met in front of Taipei’s Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in the morning. Their demands included universal insurance for farmers, reduced taxes on fertilizer, free trade of farmland and reform to farmers associations.

According to a Reading Taiwan article on the event, trouble started when the marchers reached the Legislative Yuan. Some protesters attempted to enter the building to use the restroom but were turned away by the police. Tensions rose and people started throwing cans and rocks at the authorities, who responded by arresting three protesters. Lin Kuo-hua charged the building in a rescue attempt, and was knocked unconscious and sent to the hospital. The situation worsened, and the Legislative Yuan’s sign was torn down before the angry protesters turned their attention to other government agencies. Clashes continued throughout the day as riot police arrived with barricades and water trucks, while protesters smashed the National Police Agency sign and burned cars. Gas bombs were also thrown.

Lin Kuo-hua and Hsiao were arrested around 7pm. By this time, many farmers had left, but the ranks were bolstered by angry civilians and peaceful students. The chaos continued into the night as riot police lost patience and charged the protesters, who responded with more violence and destruction. Things did not calm down until the morning. It was the most severe incident between civilians and authorities since the 228 Incident.

More than 100 people were hospitalized and 92 faced criminal charges. There was much debate on whether the violence was premeditated, as the police claimed to have found a whole truckload of rocks hidden under vegetables. Only 13 people were acquitted while Lin, Hsiao and other organizers received the heaviest sentences of nearly three years.

AFTERMATH

An investigation into the incident by Academia Sinica scholar Hsu Mu-chu (許木柱) concluded that the protesters did attack first, but also denounced the riot police for exacerbating the situation. Hsu also declared that the violence was not premeditated but a result of emotions running high on both sides.

The two Lins have conflicting opinions on the effects of this incident, both recorded in Reading Taiwan.

“If the 520 Incident hadn’t happened, there were many other farmer issues I had planned to tackle. But I noticed that most farmers became reluctant to protest. The momentum we gained after our Dec. 8 efforts was completely erased. The large-scale peasant movement that rose again after 60 years of silence was abruptly aborted,” says Lin Feng-hsi.

“I believe that the 520 incident helped the farmers greatly,” Lin Kuo-hua says. “The government started taking farmer’s rights seriously and sped up its policy reform. Our demands were eventually met, and I believe that farmers will agree with me that 520 yielded positive results.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful