Taiwan in Time: March. 7 to March. 13

As Tainan County councilor Wang King-ho (王金河) walked out of jail after 23 days for being accused of corruption by a political enemy, he decided to leave the factionalized world of politics.

“Although I was acquitted, I saw how treacherous politics could be and I was disillusioned,” Wang writes in A Memoir: Father of the Blackfoot Disease, Wang King-ho (烏腳病之父王金河回憶錄). “It was a wake up call.”

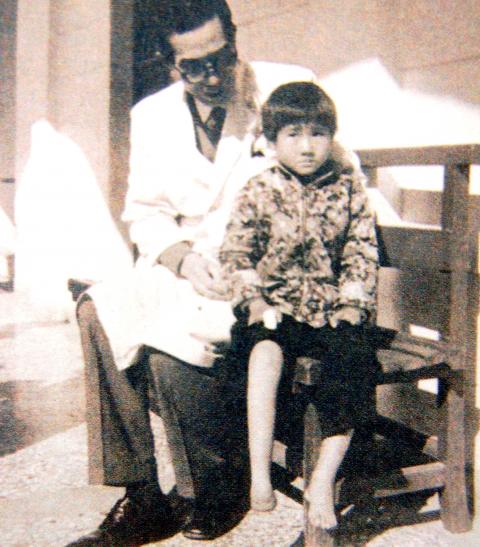

Photo courtesy of the Ministry of Culture

As a politician-doctor, Wang wrote that patients from other political factions wouldn’t come to see him, and he was straying from his goal of treating all residents of his hometown of Beimen (北門).

Returning home to practice in 1944 after the area’s only licensed physician died, Wang was first elected mayor of Beimen in 1945, and after serving two terms, he became a county councilor.

It’s a good thing Wang made his decision, because in 1956, about a year after he finished his final term as councilor, people started coming down with a strange disease on the coast of southern Chiayi and northern Tainan counties — and Beimen was right in the center of it.

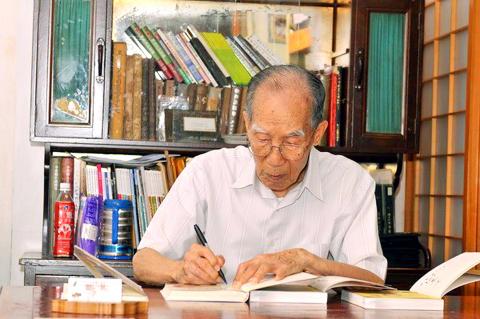

Photo: Wang Han-ping, Taipei Times

‘BLACK DRY SNAKE’

Locals called it “black dry snake” (烏乾蛇), though it’s known today as blackfoot disease. Symptoms typically began with numbness or coldness in the feet, progressing to painful gangrene as lack of circulation resulted in black, dead tissue. “Snake” referred to the way it would slowly spread up the limbs. The afflicted were usually in such severe pain that they couldn’t eat properly, and the rotting flesh often became infested with maggots. Even after amputating the limb, the gangrene could still return.

If the physical suffering — which often drove patients to bang their heads against the wall — wasn’t bad enough, Wang writes that because even relatives would keep a distance from or even shun the afflicted since they didn’t know whether it was contagious or not, even believing that it was a sort of curse for past bad deeds. Isolated and unable to work, many committed suicide.

“Their lives were a living hell with no way out,” Wang said. Since he was also the forensic pathologist, he said it especially saddened him when he examined the suicide victims.

“I swore to do all I could for my people and for blackfoot disease patients,” he said.

POISONING

The cause was later determined to be arsenic poisoning from drinking deep well water. Curiously, this type of gangrene has only been reported in Taiwan. Aside from a scare in Yilan in the 1990s, it was essentially eradicated as households started switching to tap water in the 1960s and 1970s.

At first, Wang didn’t have adequate supplies to treat the patients, and was only able to ease the pain and refer them to larger hospitals — but many were too poor to go. Soon, he was joined by researchers from National Taiwan University, who set up six free beds and provided affordable artificial limbs.

In April 1960, Lillian Dickson, a missionary who previously worked with lepers and Aborigines suffering from lung disease, arrived in Beimen. With her Mustard Seed organization, Dickson set up the Pak-mng (Beimen’s Hoklo — commonly known as Taiwanese — pronunciation) Mercy’s Door Free Clinic (北門免費診所) for blackfoot patients and asked Wang, also a Christian, if he could provide a small space in his clinic and be the main physician.

Dickson started out renting a house next to the clinic that could house six patients, but by 1966, her organization owned a two-story structure that could house 50 to 60 patients. She also provided milk and vitamins to patients and children, and helped transport children whose families could no longer provide for them to orphanages in Taipei.

Wang and his wife Mao Pi-mei (毛碧梅) were known for taking care of blackfoot patients, even personally making coffins for those without family and had young men from the church perform the funeral procession. When there weren’t enough men, nurses from the clinic helped carry the coffins.

“People were afraid to help at first, but soon everyone joined in,” he said. “This was the happiest time of my life, my golden years.”

As amputees often became beggars, Wang and Mao set up a handicraft training center for patients and later added a handicraft factory, which was run by Mao.

GOOD DEEDS

For their deeds, Wang and Mao are often referred to as “father and mother of blackfoot disease patients.”

During this time, Wang crossed paths with Hsieh Wei (謝緯), a pastor and physician who was known for his voluntary medical work with remote Aboriginal tribes. Hsieh ran the Christian hospital in Puli (埔里), Nantou County and also set up a tuberculosis sanatorium there.

Despite his regular duties, for 10 years, Hsieh would make the 300km round trip journey to Beimen every Thursday to help Wang with the amputations at no cost.

Hsieh would later relocate to Changhua, where he cared for the destitute patients there and opened a polio clinic. He would later be known as the Albert Schweitzer of Taiwan.

Wang said that he and Hsieh shared the same philosophy of being a “fool.”

“If there aren’t fools in the world, there wouldn’t be peace,” Wang recalled Hsieh saying in a sermon.

“The greatest fools in the world are parents — they take care of their children no matter how rebellious they are … Nowadays, all doctors in Taiwan want to make a lot of money and buy expensive houses and cars. But who is willing to save the patients who don’t have money? Well, I’ll be a fool if it can bring some warmth to this society.”

Wang passed away on March 13, 2014 at the age of 97.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them