Taiwan in Time: Feb. 22 to Feb. 28

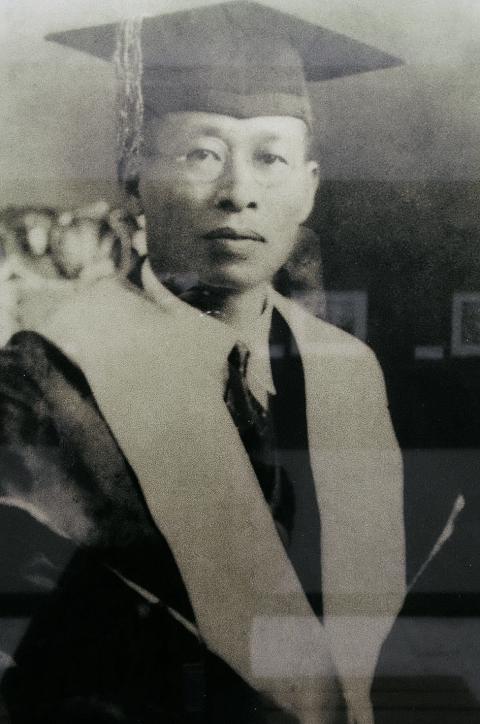

On the evening of March 11, 1947, as Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) reinforcements from China clashed with local protesters throughout Taiwan, Lin Mo-seng (林茂生), founder of the Minpao (民報) newspaper and dean of liberal arts at National Taiwan University, was reportedly escorted from his family home by six men, never to be heard from again.

As the first Taiwanese to receive a Doctor of Philosophy degree, Lin was one of many intellectuals targeted by the China-based KMT government during its violent suppression following the 228 Incident, which began as an armed local uprising. A large number of Taiwan’s private newspapers, which sprung up after Japan’s surrender in August 1945, were shut down within two weeks of the initial incident, including Lin’s Minpao.

Photo: Meng Ching-tsu, Taipei Times

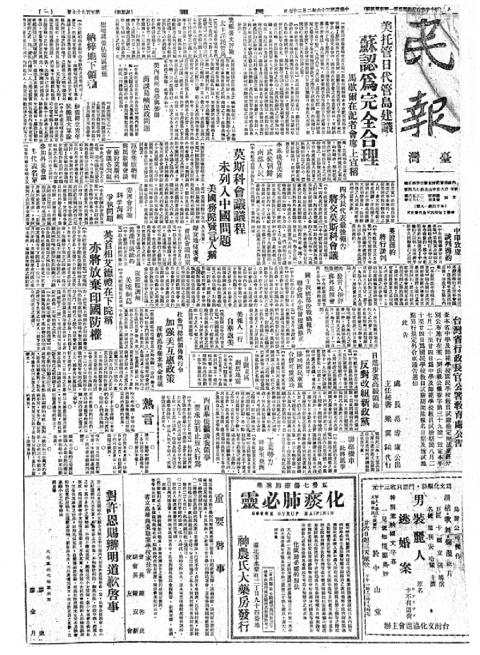

Not to be confused with the Japanese-era Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報), Lin’s paper made its debut on Oct. 10, 1945. Never afraid to criticize the government and including a column for citizen voices, it quickly became the most widely read private paper.

A quick sample of editorials during its brief existence shows titles such as “Are the People of Taiwan Really Happy?,” clearly reflecting the rising tension between local inhabitants and the newcomers from China.

One editorial, printed on July 24, 1946, even goes as far as stating that government corruption and nepotism is a “bad habit from the motherland that is now being picked up by Taiwanese.” It is not too hard to see why he would have upset the KMT.

Photo courtesy of National Library of Public Information

Interestingly, no institution in Taiwan appears to possess any record of this newspaper past Feb. 28, 1947, even though most sources have it printing its last issue on March 8, three days before Lin’s arrest.

The only reports available during the incident in the National Central Library’s newspaper archives are from the Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News (台灣新生報), which was the official publication of the Taiwan Provincial Government, and the KMT-run China Daily News (中華日報).

The book, Lin Mo-seng, Chen Hsin and Their Era (林茂生, 陳炘和他們的年代) details Lin’s final days, as told to author Lee Hsiao-feng (李筱峰) by Lin’s son, Lin Tsung-yi (林宗義).

The younger Lin recalls his father responding to the incident, saying “Taiwanese are ready to tell the Mainlanders that we have had enough of being treated as second-class citizens, and we have had enough of authoritarian rule and government corruption that has been going on since October 1945.”

But Lin also denounced the use of force against the government, warning that violence is an ineffective method that would lead to disastrous results.

“The key to our future is democracy and respectful relations between Taiwanese and Mainlanders. We [Minpao] still face a momentous task in front of us,” he adds.

On March 4, after meeting with the 228 Incident Resolution Committee, Lin lamented to his son that this uprising lacked clear leadership and organization and that it was going nowhere.

The next day, Lin’s Japanese friend warned him that he was in danger. Even though Lin didn’t overtly participate in the uprising, he and his newspaper’s influence in society already posed a threat to the KMT.

On March 8, Taiwan governor Chen Yi’s (陳儀) reinforcement troops landed in Keelung as the government rejected all 32 demands made by the resolution committee, and the crackdown became increasingly violent. Minpao’s office was destroyed that night.

Lin Tsung-yi was notified by a servant of his father’s arrest in the morning of March 11. When Lin Mo-seng’s wife asked the men where they were taking him, one of them reportedly replied, “We’re going to see Chen Yi.”

Official charges against Lin included plotting rebellion, encouraging [NTU] students to riot and attempting to use international interference to achieve Taiwanese independence.

Most historians agree that the real reason Lin was arrested was because of his newspaper’s criticism of the government. And it was not just Lin.

The publishers of other private newspapers, such as the People’s Herald’s (人民導報) Wang Tien-teng (王添?) and Ta Ming Pao’s (大明報) Ai Lu-sheng (艾璐生), were also taken away never to be seen again.

But the most curious part of this is that even Juan Chao-jih, (阮朝日), general manager of the government’s Shin Sheng Daily News, became a victim of this media purge, together with editor Wu Chin-lien (吳金鍊) and other staff members.

On March 25, the Shin Sheng Daily News announced its new general manager and editor-in-chief, who were high-ranking military and government officials.

What happened to these people and how the newspaper’s coverage changed under the new management will be examined in next week’s edition of “Taiwan in Time.”

Part II appears in next Sunday’s Taipei Times.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,