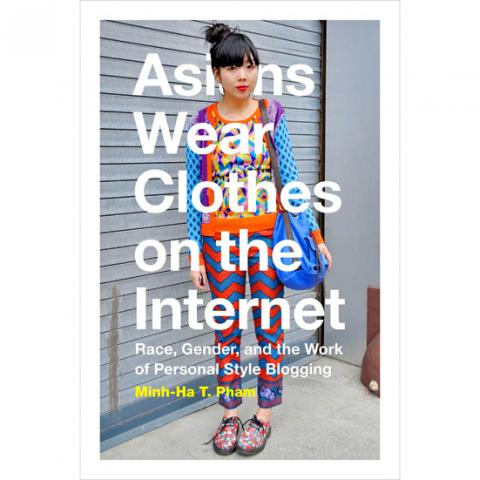

This is a book about a Filipino who calls himself “Planet Earth’s favorite third-world fag” and a Chinese-American who hides her face in her photos because she thinks her eyes are ugly. Both have had their “signature” poses replicated by celebrities in advertisements for some of the world’s fashion icons such as Marc Jacobs. Both have massive followings for, well, wearing clothes on the Internet. They are among an elite group of Asian personal-style “super bloggers,” as Minh-Ha Pham calls them, in this study of race and gender in the world of online fashion blogging.

Pham says that Asians, especially females, occupy two extremes of the clothing industry: the numerous garment factory workers around the world often performing repetitive tasks under what we don’t like to call sweatshop conditions, and the bloggers such as Susanna Lau (Susie Bubble), Aimee Song and Bryan Yambao (BryanBoy).

Pham’s book, which takes a scholarly approach to phenomena we run across everyday on the Internet such as mirror selfies and fashion blogger poses, argues that, on the surface, the rise of Asian bloggers heralds a “racial democratization” of the fashion world and signifies that people of any background can have a piece of the (still) Caucasian-dominated industry. However, she says it’s an illusion that obfuscates persisting racial stereotypes existing since Asians started moving to the West.

What these bloggers are doing may be simple (hence the ultra-straightforward book title) but as the subtitle suggests, there is much to discuss and think about along racial, social and financial lines. Just as how the photos these bloggers produce of themselves completely conceal all the work that goes into making being fashionable seem “effortless,” Pham writes that when race is “embedded in digital technology and practices,” sometimes it becomes invisible to human perception.

The book starts from the global social, technological and financial conditions that led to this phenomenon, to how bloggers write, pose, assume certain gender and racial roles all while providing a look into the sociological mechanisms of the “participatory culture” of the Internet. The language, since it’s an academic work, can be dense and repetitive at times as Pham tries to reinforce her points — which could be conveyed in much shorter length — but overall it’s not a difficult book to understand.

Pham sees the Asian blogger phenomenon as one of many paradoxes. As much as it is an opportunity for Asians, she still finds parallels between the blogger and the garment worker, which loosely becomes the central theme of the book.

Is this phenomenon actually empowering Asians and giving them unprecedented opportunities, or are they still being exploited by the system under the guise of multiculturalism? Pham doesn’t have all the answers, but she provides a pretty thorough analysis, as far as explaining why Asians have been successful in the field so far.

It’s worth noting that despite their success, it’s just a tiny add-on to the fashion industry as a whole, which is still Caucasian-dominated. Pham writes that while these Asians are able to use their racial differences (and even stereotypes) to their advantage amid the increasing global popularity of Asian culture and emerging Asian luxury markets, they still have to play by the rules.

One of the more intriguing points of the book is the degree of “differentness” that a minority can display without making the majority feel uncomfortable or threatened. While these bloggers look Asian and express certain traits that are perceived as Asian such as “cuteness,” they are fluent in English, attuned to Western culture and are relatable enough that the majority would follow and even mimic them.

While the hows are explained well, some of the racial explanations for certain behavior feel like borderline over-analysis, especially when you’re writing about a very select group of individuals. While most of Pham’s arguments make sense on a logical level, at times it left me wondering if I am really that oblivious to certain racial injustices carried out by the majority or whether Pham is simply reading too much between the lines.

For example, she attributes certain phenomena to the bloggers being Asian — such as how they conceal the work that goes into making a blog post to counter the sweatshop stereotype — but really, this type of action is universal in the blogosphere regardless of race, as people in today’s instant-gratification Web culture probably wouldn’t want to see photos of them shopping or editing their photos. They just want the end product.

There are a few mainstream articles Pham sees as singling out Asian bloggers as tacky, unethical and trying too hard, but as she mentions throughout the book, the original and most prominent fashion bloggers are Asian, so they could naturally make for an easy target. If there were any counterexamples of Caucasian bloggers and media coverage of them, the argument would be stronger, but unfortunately the book barely mentions any, which is another glaring problem.

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman

The Venice Film Festival kicked off with the world premiere of Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia Wednesday night on the Lido. The opening ceremony of the festival also saw Francis Ford Coppola presenting filmmaker Werner Herzog with a lifetime achievement prize. The 82nd edition of the glamorous international film festival is playing host to many Hollywood stars, including George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Dwayne Johnson, and famed auteurs, from Guillermo del Toro to Kathryn Bigelow, who all have films debuting over the next 10 days. The conflict in Gaza has also already been an everpresent topic both outside the festival’s walls, where

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and