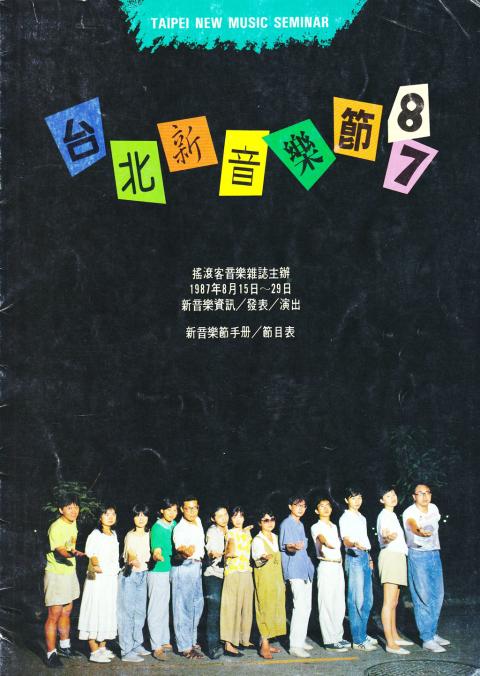

A little known folk song movement and a noise campaign are two examples featured in ALTERing NATIVism Sound Cultures in Post-war Taiwan (造音翻土──戰後台灣聲響文化的探索), a newly published book based on a series of lectures and exhibitions that examine the development of Taiwan’s alternative music and sound art in a political context.

According to curator Amy Cheng (鄭慧華) and music critic Jeph Lo (羅悅全), who co-edited the book together with music critic Ho Tung-hung (何東洪), the 300-page book, which is composed of articles by 26 music critics, artists and scholars, explores the relationship between music and the country’s democratic development from the beginning of the Martial Law era in 1949 to the present, and examines how musicians and artists reflect on and help shape national identity through their work.

SOUND PROJECT

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

Ever since the inception of TheCube Project Space (立方計畫空間), an art space Lo and Cheng co-founded in 2010, the pair have used it as a platform to carry out curatorial and research projects on Taiwan’s sound culture, a term they use to refer to all kinds of music and other audio creations, ranging from folk, rock and electronic music, to experimental sound and sound art.

The project developed through a series of lectures and exhibitions by musicians and contemporary artists and morphed into large-scale exhibitions at the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (MoNTUE, 北師美術館,) and the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts (高雄市立美術館) last year. Those exhibitions received the grand prize at this year’s Taishin Arts Award (台新藝術獎).

ALTERING NATIVISM

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

Lo and Cheng say it is essential to examine this bit of history so as to identify how sound cultures have evolved and influenced society. One of the book’s key words is nativism, a term that refers to bentuhua (本土化), which can be translated as localization, Taiwanization or nativization. Lo says Taiwan, due to it being colonized many times over its history, has become a multicultural country where the identity of its people is constantly being redefined.

“Nativism means an ever-changing process through which you see and identify yourself,” Cheng says.

“Another point is to see ... how music plays an active role in facilitating such changes,” Lo adds.

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

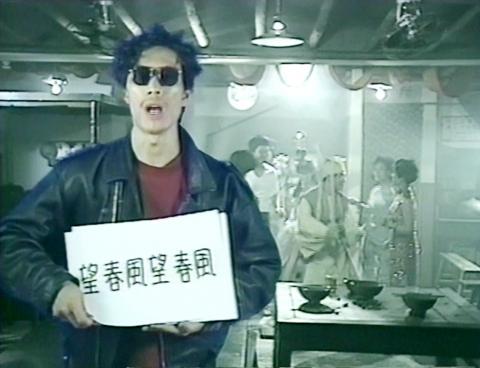

The now-defunct Crystal Records (水晶唱片), opened after martial law was lifted in 1987, is recognized as an important force behind the quest for nativism. Along with a new generation of independent musicians and groups such as Chu Yueh-hsin (朱約信), Chen Ming-chang (陳明章) and Black List (黑名單工作室), the indie label initiated what has come to be known as the “New Taiwanese Music” (台灣新音樂) campaign to produce and promote alternative music, with musicians drawing inspiration from Taiwanese musical traditions to create songs in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese) that are socially and politically relevant to the new democratic reality.

“Crystal Records offers a good example of how musicians combine traditional Taiwanese songs with folk, rock and electronic music to give the traditional a new face that is meaningful and relevant to the present day,” Lo says.

ALTERNATIVE SOUNDS

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

A play on the word alternative, the title of the book also serves as a rallying cry for social and political activism.

Folk musicians such as Li Shuang-tze (李雙澤) and Yang Tsu-chuen (楊祖珺) were part of a thriving folk song movement (民歌運動) in the 1970s who made social activism part of their music and sang about the socially disadvantaged. But the authorities soon banned them.

Fast-forward to the 1990s, music and activism went hand in hand for protest bands like Black Hand Nakasi (黑手那卡西), which collaborated with and held workshops for the working class, and Labor Exchange (交工樂隊), which was formed by Zhong Yong-Feng (鍾永豐) and Lin Sheng-xiang (林生祥) during protests against the building of the Meinung Dam (美濃水庫) in 1992.

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

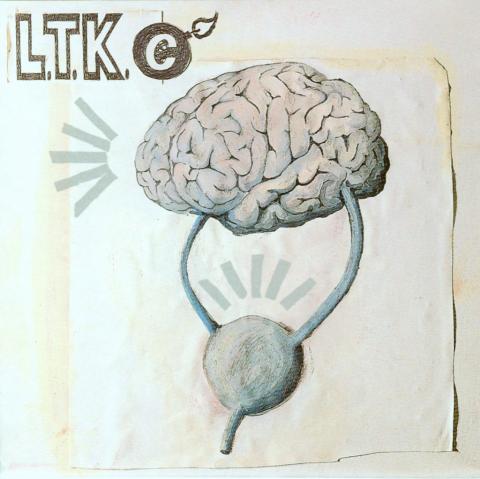

The early 1990s also saw the short-lived noise movement led by LTK Commune (濁水溪公社) and Zero and Sound Liberation Organization (ZSLO, 零與聲音解放組織). In his article, sound artist Lin Chi-wei (林其蔚), a founding member of ZSLO, gives a detailed account of how, in the aftermath of the end of martial law and the Wild Lilies student movement (野百合運動), young artists, musicians and anarchists used music as a creative outlet to raise awareness about social issues.

The book includes many rare documents. A manifesto by LTK proclaims that “punks, drug dealers, queers and scumbags” should create a new social order. A flyer of the legendary Taipei Broken Life Festival (破爛生活節), which featured high-frequency noise performances and violent, provocative acts (performing colon cleansing using yoghurt and setting fire to the stage) that “forced most of the audience to flee from the scene.”

A NEW MILLENNIUM

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

ALTERing NATIVism ends in the new millennium with sound art by groups such as Lacking Sound Festival (失聲祭) and Etat (在地實驗).

Lo and Cheng say these artists are unique in the way they collaborate and form their own platforms, not only as artists and performers, but event planners, Web managers and publishers.

“In the 1990s, young people did what they did out of a sense of urgency. They [gave] the middle finger to the establishment. They didn’t organize. They were anti-institutional,” Cheng says, adding, “today’s young artists tend to organize, create their own alternative platforms and connect to the rest of the world.”

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

ABORIGINAL POP

The book also discusses Aboriginal music — in particular, the largely unknown Aboriginal pop music.

According to academic Huang Kuo-chao (黃國超), Aboriginal pop developed and flourished outside the Han-Chinese music industry. It had a different mode of production and circulation, with pop stars and singers whose names were mostly unheard of to non-Aborigines.

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

“It is the alternative of the alternative,” Lo says. “This topic alone is worth writing a book about.”

A scaled-down exhibition of ALTERing NATIVism Sound Cultures in Post-war Taiwan is currently on display at MoNTUE, as part of the 13th Taishin Art Award Exhibition (第十 三屆台新藝術獎大展), which runs through July 26. The Taishin exhibition showcases five winning works, including Yuan Goang-ming’s (袁廣鳴) video art series An Uncanny Tomorrow (不舒適的明日) and Tsai Ming-liang’s (蔡明亮) theatrical work The Monk from Tang Dynasty (玄奘).

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

Photo courtesy of TheCube Project Space, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, MvoNTUE and Taishin Bank Foundation for Arts and Culture

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

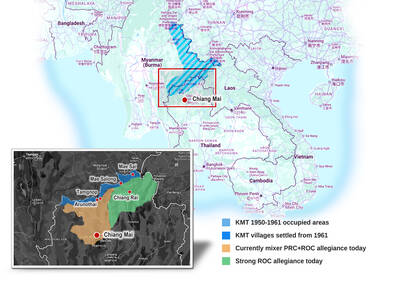

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.