Liao Chien-hua’s (廖建華) knowledge of Taiwan’s political past used to be limited to a bunch of dates. It wasn’t until friends and schoolmates from National Tsing Hua University (NTHU) took part in the anti-media monopoly protests in 2012 that the chemical engineering major started to read about Taiwan’s history.

“For many young people, including myself, the anti-media monopoly movement opened up a window to a different world,” Liao, who was born in 1990, says.

Liao soon read the Oral History of Su Beng (史明口述史). Su Beng (史明), 96, is a veteran Taiwan independence leader and founder of the Taiwan Independence Association (TIA, 獨立台灣會). Liao was shocked to learn that in 1991, four years after martial law was lifted, Investigation Bureau agents broke into then-NTHU student Liao Wei-chen’s (廖偉程) dorm room, arrested him and charged him with sedition.

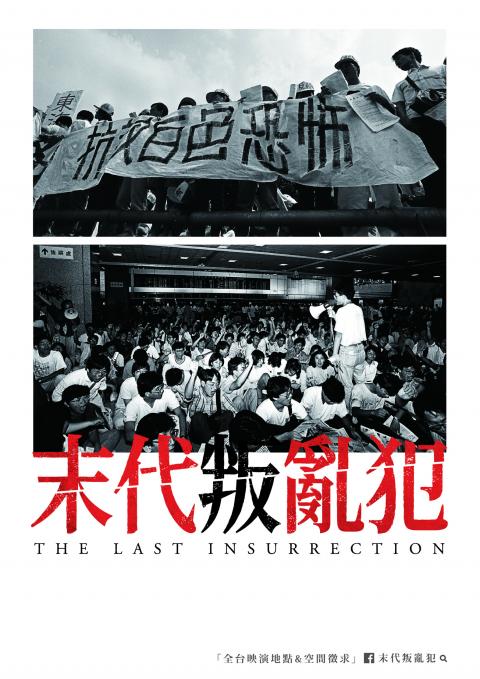

Photo Courtesy of The Last Insurrection crew

Known as the Taiwan Independent Association incident (TIA, 獨台會案), Liao Wei-chen was one of four individuals accused of organizing pro-independence activities under Su’s guidance. If found guilty, they would face the death penalty under the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例).

The arrests triggered a student and activist occupation of the Taipei Railway Station. A few days later, the legislature abolished the Punishment of Rebellion Act, and the four were immediately freed.

Liao Chien-hua, who had never heard of the incident, was intrigued. In 2013, he started a documentary project on the incident with three NTHU friends, all born after 1990. Two years later, having interviewed 46 victims, activists and officials, the film, The Last Insurrection (末代叛亂犯), is nothing like what they had planned it to be.

Photo Courtesy of The Last Insurrection crew

The filmmakers originally intended to focus on Liao Wei-chen because he was the subject of most of the information they found.

“But then, we learned that there were a lot more things we didn’t know,” Liao Chien-hua said. “There was virtually no mention of the other people who got arrested ... It raises a problem: in official history, there is no room for the socially disadvantaged.”

REDISCOVERING HISTORY

Photo Courtesy of The Last Insurrection crew

The other three arrested were Aboriginal rights activist Masao Nikar, political activist Wang Hsiu-hui (王秀惠) and cultural historian Chen Cheng-jen (陳正然). None of the four knew each other. The only link was that they studied Su’s 1962 book Modern History of Taiwanese in 400 Years (台灣人四百年史) and some had visited Su, who was then living as a political refugee in Tokyo.

Fu Jen Catholic University professor Ho Tung-hung (何東洪), who participated in the Wild Lily Student Movement (野百合學運) in 1990 when he was a student, says it was a frightening time.

“Everybody was scared ... All of a sudden, the White Terror became so real. It was not something in the past or imagined,” Ho said at a forum after a screening of the documentary organized by the Green Party Taiwan earlier this month.

Back then, Su’s book was banned, but “everybody had a copy of it,” Ho added, recalling a newsstand during his days at National Central University that sold “everything that was banned,” — from dangwai (黨外, or non-Chinese Nationalist Party) publications to pornography.

THE OMISSION

The Last Insurrection features commentaries about the incident from many instantly-recognizable faces such as Cheng Li-chun (鄭麗君), Lin Chia-lung (林佳龍) and Chen Shih-meng (陳師孟). But there are also a few who have remained largely unknown.

Masao, an Amis who became an Aboriginal rights activist, works as a pastor in Hualien. In the documentary, he says that Aboriginals think that Taiwan’s history spans thousands, not hundreds, of years.

The filmmakers discovered that Wang, who died a few years after the incident, was born and raised in poverty, and was a single mother who worked odd jobs to support her family. She was a member of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) as well as the Formosa Political Care Foundation North Branch (台灣民主運動北區政治受難基金會, FPCF), an organization set up in 1987 by dangkung (黨工), which refers to people who carry out political activities at the grassroots level — laborers and small business owners, for example, that were “looked down on and discredited by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime as the slipper-wearing, betel nut-chewing, Taiwanese-speaking boors,” Ho says.

Liao Chien-hua says that FPCF was like a self-help group for dangkung. Back then, many were injured and arrested during street protests and clashes with the police. They were often the breadwinners of their families. But they mostly went unnoticed, Liao says.

In the film, Wang’s close friend Chuang Shu-hui (莊淑惠), a former dangkung, laments that no one knew or cared when Wang died. Tsao Ai–lan (曹愛蘭), then-vice president of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights (台灣人權促進會) who became a friend of Wang’s, discusses the sexual discrimination facing female activists of that time.

She says many saw Wang as a butterfly who “sold her sexiness” because she dressed in a feminine way.

“Male politicians didn’t want us to befriend their wives because they thought we were a bad influence,” Tsao adds.

Liao Wei-chen says it is remarkable to see how the young filmmakers have formed their own opinions.

“I really like the way they choose to approach the incident. Past documentaries always focus on students: ‘Look, it is students occupying the train station.’ It’s as if there is something very noble about students who protest,” he says.

“It is like the Sunflower movement. There are many social forces behind it, but it is still labeled as a student movement,” he adds.

FILLING A VOID

Since last month, The Last Insurrection has been screened at venues across the country, ranging from colleges and universities, libraries to independent bookstores, small cafes, restaurants and bars. Most viewers are in their twenties, and may not have any idea about many of the events, names, ideas and terms mentioned in the film, according to Liao Chien-hua.

But he says that it’s a good start by writing “Masao Nikar and Wang Hsiu-hui back into history.”

Liao Chien-hua says he will continue to make documentaries about lesser-known historical events during Taiwan’s democracy movement in the late 80s and early 90s, through the eyes of participants or those who lived through it.

“I think we have come to know that our understanding of history is easily shaped by official ideology. What interests me more now is what people of different genders, ethnicities and classes have to say,” he says.

For more information about the documentary, visit www.facebook.com/fromInsurrectiontoInnocency

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word

The central government sets the nation’s environmental strategy and directs the push for net zero. It proposes laws and decides how most tax dollars are spent. The country’s local governments aren’t powerless, however. They draft local ordinances, assign manpower to carry out inspections, and — a recently-published assessment of environmental governance at the city/county level makes clear — have their own priorities. On Dec. 24, the Taiwan Environmental Protection Union (TEPU, 台灣環境保護聯盟) released its latest Municipal and County Government Sustainable Governance Evaluation Report. After analyzing 99 metrics, the NGO declared that the environment-related policies and implementation of Kaohsiung City, Tainan City