When the Sunflower movement started, I was in Toronto giving a seminar and teaching a class on President Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) government reform of Taiwan’s history textbooks. I was about to leave my hotel for the university to give the last seminar, when I received a text message from Taiwan telling me that students opposing a trade deal with China had just stormed the Legislative Yuan.

I instantly thought: Am I like Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙), about to miss the beginning of a revolution? My plane was leaving that night, which means that I would arrive on the second day. Will police have cleared the site by then? But, of course, I was no Sun Yat-sen, having inspired no revolution.

GAME CHANGER

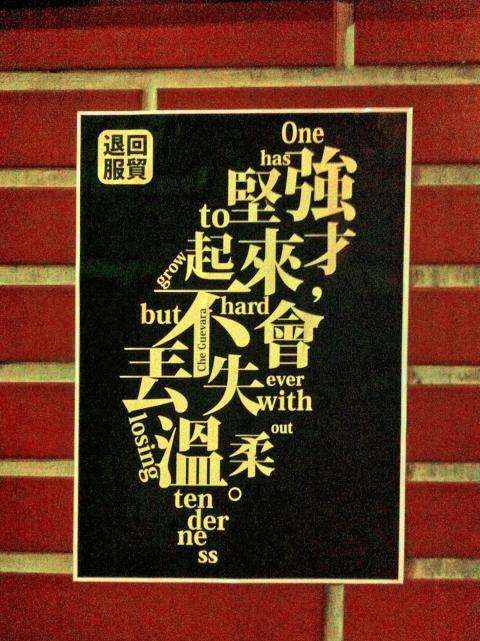

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The astonished audience in Toronto discussed the occupation as it unfolded in real time — something even up to a decade ago was unthinkable in a venue held so far way from the field.

Information technology has changed not only the way people mobilize, but also how scholars document ourselves and reflect on events. No one can roll back such a significant development, however terrifying it might seem. Today, the amount of time some scholars and elected politicians spend on Facebook, blogs, Twitter and other social media, distracts them from reading, thinking and conducting interviews in the field, immersed for weeks and months in other people’s lives far away from our offices. And now, the movement was just about to unite the two, by giving a chance to so many scholars to spend nights and days with students on the ground. The core mission of scholars and politicians — to think slowly and wisely about our society, its problems, its reforms, its future — has become increasingly difficult. Reading books are now a luxury, but we now have to admit that fieldwork has been restructured in many ways by technology.

I arrived back in Taipei on the afternoon of day two of the occupation. Thanks, globalization. I do not particularly like you, but you did me a favor on that day.

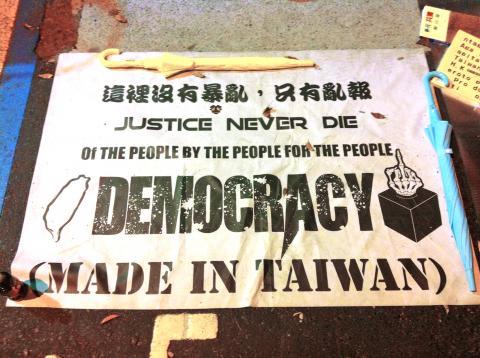

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The reason I wanted to return so quickly is obvious: Like other academics specializing in Taiwanese identity politics and geopolitics in the Taiwan Strait, I wanted to understand what was happening on the ground. Would it be a turning point? Would the government send in troops? Would China, whose rulers had repeatedly said for 20 years that political turmoil and major social instability in Taiwan would be a reason to intervene, remain silent or enter a new phase of relations?

Such questions were not meaningless. As we know, it turned out that the government did not send in the military (at least not into the legislature), China was shocked and in spite of its long standing menace, did not intervene. And yes, it was, from many respects, a turning point.

Before arriving back in Taipei, I couldn’t help but think that the storming of the legislature would instantly become a historical event. How come, as a scholar taking particular care in using words, could I consider an event as becoming instant history, as if it were instant noodles?

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The storming of Taiwan’s legislature appeared to many as brave (it was) and unprecedented. But the fact is that it was neither unique, or a first. Indeed, each time a legislature is stormed, occupied, defended, shielded or burnt, by pro-democracy forces or anti-democracy ones (when we can distinguish them), it “makes history” because it reveals an impasse in dialogue between political forces. In many cases induces historical change. Storming and occupying a legislature, however brief, is not so rare in history, and each time it happens, it underlies the major significance of what a legislature is and what is at stake.

PRECEDENTS

Three historical events and memories came back to me before I landed in Taiwan last March. The first, in 1993, the shelling of Moscow’s parliament, in the midst of the conflict between Boris Yeltsin and the undemocratic Russian Federation’s Supreme Soviet. I was amazed at this black building called the White House, exploding on its right side by the shelling of Yeltsin forces — in the name of democracy. In 2011, hundreds of militants stormed the parliament of Kuwait, demanding the resignation of Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah, who indeed later resigned as prime minister. Was that the start of a huge movement in the Arab world?

In January and February 1997, Bulgaria made world headlines — a rare event — when thousands of protesters laid siege to the parliament, while the country was under hyperinflation, and asking for the government to resign. The protests were led by students.

After a few days, I realized that these events had in fact been quite frequent in history, especially in recent years, though each time happening in different contexts, with different groups, different ideologies, different aims. Many more examples could be found both recently and in earlier times: Burkina Faso in October 2014, Iran in 1908, Serbia in 2000, Canada in 1849. There are, however, major differences: the Taiwan occupation was apparently unique in being long, non-violent, massive and ending peacefully, compared to other national experiences.

THE TAIWAN DIFFERENCE

Storming the legislature was described as an extreme measure by both sides — on one side to denounce the non-respect of representative democracy; on the other, to denounce a “bird-cage democracy” in Taiwan that would lead students to this “last-resort” means to have their voices heard. But, if we bear in mind the existence of so many precedents, occupation of the houses of government are a regular occurrence in the course of democratic development and consolidation, since a perfect and satisfactory representative democracy remains an ideal pretty much everywhere.

And what is legal is not necessarily democratic, just as something which is technically illegal is not necessarily undemocratic. Violence is obviously a sign of failure in discussion and negotiations. But the use of the words “symbolic violence” to qualify a breach of representative democracy is a double-edged sword, as the meaning of the phrase (A necessary evil? A dangerous act?) depends heavily on the political ideology of the one who uses it.

On day two, my field work could start: observing, asking rare questions, mainly listening to what people had to say, taking pictures (lots of pictures), collecting leaflets. And, many more days before the student movement announced its dissolution, thinking about the question: How to collect those historical memories? To the students I met there, and who were sensitive to this question (most were not until the very last moment, after the dissolution was announced), I asked: “We have pictures of the Tiananmen protests and of the Wild Lily movement, but where are the artifacts? Almost none are left.”

If the Sunflower movement belongs to Taiwanese and their history, we as scholars, had a responsibility to collect these visual traces — leaflets, banners, stickers, works of art, posters and so on. So that, regardless of the ideology of future researchers, and hopefully they’ll remain neutral, they will be able to study, display and share those artifacts that made history.

Stephane Corcuff is an associate professor of political science at the university of Lyon, and a researcher at the French Center for the Study of Contemporary China in Taipei.

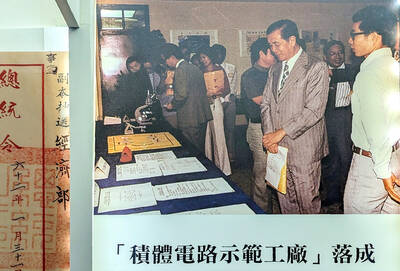

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,