“How is it possible for a documentary filmmaker to capture the life of Su Beng (史明)?” director Chen Lih-kuei (陳麗貴) asks in the beginning of Su Beng, the Revolutionist (革命進行式). It is a fair question for anyone facing the enormity of a life like that of the lifelong Taiwanese independence campaigner.

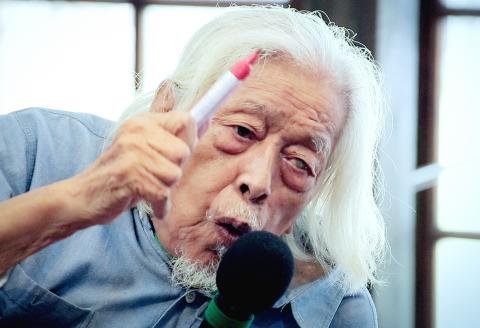

You might have seen Su in an Association for Taiwan Independence (ATI, 獨立台灣會) motorcade. Rain or shine, Su, now 97 years old and blind in one eye, is always standing atop one of the slow-moving trucks in Taipei to deliver messages on nationalism and Taiwanese independence through megaphones.

YOUNG REVOLUTIONARY

Photo Courtesy of Chen Lih-kuei, Hsu Hsiung-piao and Su Beng Education Foundation

Born Shih Chao-hui (施朝暉) to a wealthy family in Taipei’s Shilin District (士林) in 1918, Su became a Marxist at Waseda University in Tokyo — a school known for its liberal environment. With the intention of resisting Japanese imperialism, he moved to Shanghai to join the Red Army after graduating in 1942, but was quickly disillusioned with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) after witnessing the extreme brutality it comitted in name of revolution.

Su returned to Taiwan in 1949, two years after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) massacred over 20,000 people in an uprising which came to be known as the 228 Incident. The trained undercover agent set up the Taiwan Independence Revolutionary Armed Force (台灣獨立革命武裝隊) in 1950, buying guns and hiding them in Yangmingshan (陽明山) in preparation for a plot to assassinate Chiang.

When the plot was compromised, Su fled to Japan in 1952, where he continued to stay after being granted political asylum. He opened a noodle shop in Tokyo, which served as a base for training underground members to carry out anti-government initiatives and as a meeting point for young activists such as the late Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) politician Lu Hsiu-yi (盧修一).

Photo Courtesy of Chen Lih-kuei, Hsu Hsiung-piao and Su Beng Education Foundation

Su spent all his earnings from his noodle shop on funding underground operations. Before 1975, he plotted arson attacks on police stations in Taiwan and planned to damage railway tracks and military trains with handmade explosives. He had strategic and technical support from the Japanese Red Army (JRA), a communist military group formed in 1970 with the objective of overthrowing the Japanese government and monarchy and unifying the world under communism.

It was during this time that Su established the ATI. Unlike most of the overseas pro-independence groups formed by students and intellectuals at the time, the members were largely gangsters, small business owners and commoners — rather than being from the social elite. Su’s radicalism distanced him from most independence activists.

At the same time as plotting a revolution and running a noodle shop, Su found time to write a book. His Taiwan’s 400-Year History (台灣人四百年史), first published in Japanese in 1962, offered a theoretical base for building Taiwan as an independent nation-state with an equitable distribution of wealth.

A wanted man under KMT rule for more than four decades, Su was only able to return to Taiwan in 1993, six years after martial law was lifted.

CONNECTING WITH YOUTH

In 2012, inspired by a cultural forum on Su organized by the Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Research Institute (蔡瑞月舞蹈研究社), writer and veteran journalist Ho Rong-hsing (何榮幸) and Democratic Progressive Party legislator Pasuya Yao (姚文智) made a film recognizing Su’s contribution.

Having produced a series of documentary works about Taiwan’s democracy, including Dear Taiwan (好國好民), which tackles the subject of Taiwanese identity, filmmaker and social activist Chen was asked to complete the project, with Yao as producer.

“I started out thinking that a film about a nonagenarian must all be in the past tense. I was so wrong,” Chen says.

Nicknamed Ojiisan (歐吉桑) — which is Japanese for “grandfather” — by young activists and students, Su has regained recognition during the waves of student movements in recent years. The Oral History of Su Beng (史明口述史), drawn from 30 interviews conducted by a team of college students over the period of six months between 2009 and 2010, was published in 2013. Nowadays, Su is often surrounded by 20-somethings as he gives lectures on campuses across the country.

Chen believes that Su’s undying idealism resonates with aspiring young minds. To reflect this in the film, Chen interweaves Su’s past and present instead of following a chronological narration. The film contains interviews with young activists such as Jiho Chang (張之豪) and Lan Shi-bo (藍士博) on how they view Su, as well as footage of Su’s speech in front of Sunflower movement participants at the Legislative Yuan last year.

“In my generation — those who are 50 to 60 years old — left-wing thought was something to be repressed, be afraid of and made illicit. Su was the kind of person we were suspicious of and kept a distance from…. Now, the young generation embraces leftism as class conflict and social inequality have worsened,” Chen says.

“I find it very interesting that Su has skipped a few generations and now clicks with young activists and students. My generation is corrupt and beyond cure. I hope this film will speak to younger generations,” she adds.

UNEARTHING THE PAST

The filmmaking process was a challenge for Chen since traces of Su’s life were erased by the activist himself. Documents regarding military campaigns and other underground activities were destroyed, and photographs were rejected in order to protect others.

In the film, Su’s past is vividly reenacted, yet it is the present that allows us to see Su’s strength as a human being. Chen’s sober lens reveals an aged man, painfully and slowly taking one step at a time as he walks to his room, visibly exhausted after each speech. In one scene, the camera lingers quietly on Su’s withered body, as he dons a swimsuit for a swim — a form of exercise he maintains to stay physically fit for his campaigns.

“Don’t help me. Just pull me up if I fall,” Su says to A-chung (阿忠), his assistant who moved in with him after his home was seized by an army of roaches.

The film also introduces us to Su’s lover and work partner, a Japanese woman named Kyoko Hiraga. Escaping from China to Taiwan with Su, the couple stayed together for more than 20 years before they broke up in the 1960s.

A more personal story emerges as we hear Hiraga recounting their time together. To the question about their break-up, the octogenarian lady replies: “women.”

Meanwhile, the film spends less time on Su’s armed resistance activities. Chen points out that it is because there is virtually no archival information, nor could they find anyone other than Su who can speak of it in front of the camera.

“It will be interesting to make a documentary about Su’s connection with the JRA, but finding someone still alive and willing to talk is a very difficult task,” she adds.

As Academia Sinica Institute of Taiwan History associate research fellow Wu Rwei-ren (吳叡人) says in the film, the significance of Su’s organized resistance doesn’t lie in how big the impact it made, but the indication of Taiwan’s presence in the world history of armed revolution.

Su Beng, the Revolutionist opens in theaters nation-wide on Thursday, just in time for 228 Memorial Day activities. It is 127-minutes long, in Hoklo, Japanese and Mandarin with Chinese subtitles. For more information, check out: www.facebook.com/subengmovie.

In recent weeks the Trump Administration has been demanding that Taiwan transfer half of its chip manufacturing to the US. In an interview with NewsNation, US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick said that the US would need 50 percent of domestic chip production to protect Taiwan. He stated, discussing Taiwan’s chip production: “My argument to them was, well, if you have 95 percent, how am I gonna get it to protect you? You’re going to put it on a plane? You’re going to put it on a boat?” The stench of the Trump Administration’s mafia-style notions of “protection” was strong

Oct. 6 to Oct. 12 The lavish 1935 Taiwan Expo drew dignitaries from across the globe, but one of them wasn’t a foreigner — he was a Taiwanese making a triumphant homecoming. After decades in China, Hsieh Chieh-shih (謝介石) rose to prominence in 1932 as the foreign minister for the newly-formed Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in today’s Northeast China. As ambassador to Japan, he was to represent the last Qing emperor Puyi (溥儀) at the event’s Manchuria Pavillion, and Taiwan’s governor-general welcomed him with the honors of a state guest. Hsieh also had personal matters to attend to — most

Late last month US authorities used allegations of forced labor at bicycle manufacturer Giant Group (巨大集團) to block imports from the firm. CNN reported: “Giant, the world’s largest bike manufacturer, on Thursday warned of delays to shipments to the United States after American customs officials announced a surprise ban on imports over unspecified forced labor accusations.” The order to stop shipments, from the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), came as a surprise to Giant, company officials said. Giant spokesman Ken Li (李書耕) said that the CPB never visited the company’s factories to conduct on-site investigations, nor to interview or

Despite an abundance of local dance talent, Taiwan has no renowned ballet company to call its own. But great troupes do visit — including the English National Ballet this past May. And once a year, Art Wave’s (黑潮藝術) annual Ballet Star Gala brings together some of the world’s pre-eminent principal dancers for a cornucopia of pas de deux. Organizer Wang Tzer-shing (王澤馨) said this year’s edition of the gala, to be staged today and tomorrow at the National Theater in Taipei, is exceptionally balanced between classical and modern ballet styles. Modern ballet pieces by prominent choreographers — Rudi van Dantzig, essential to