With white walls and acrylic paintings of abstract nature scenes ranging from baby blue to deep blue, Yosifu Contemporary Taiwan Aboriginal Art on Jinshan South Road is an oasis in the middle of the urban sprawl that is Taipei.

Dressed in khaki shorts and flip-flops, artist and gallery director Yosifu, who is from the Amis tribe in Hualien, says his gallery is an open and inclusive space that defies perceptions of Aboriginal people.

“I wanted to set up a different kind of gallery where people can walk in with slippers and take pictures,” says Yosifu.

photo: Dana Ter

He adds that “people normally think that an Aboriginal art studio needs to look very ‘traditional’ and include lots of wood and stone carvings.”

Yosifu is one of the few Aboriginal artists from Taiwan to achieve international acclaim, having participated in art festivals all over Europe and Asia. He identifies not only with being Amis, but as a “global person” — the result of traveling to over 40 countries and dividing his time between Scotland’s Edinburgh and Taipei for the past 15 years. As such, his artwork is a means of communicating Aboriginal culture while simultaneously raising awareness of global issues like environmental destruction.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

photo: Dana Ter

This dual message is evident in many of his paintings. The ocean is Yosifu’s muse — his piece Blue Diamond (藍色鑽石), for instance, is inspired by the seven seas.

Yosifu says he is constantly questioned by reporters who make remarks such as, “I don’t see any elements of Aboriginal culture in your abstract art.”

Unfettered, he sees these questions as educative opportunities to explain the meaning behind his artwork.

photo: Dana Ter

“The message is not just Aboriginal, Aboriginal, Aboriginal,” said Yosifu.

“Amis culture is closely connected with nature, but pollution and nuclear waste affects everyone and destroys everyone’s environment,” he adds.

Yosifu’s paintings depict his impressions of the rice paddies in his native Hualien to the corals in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Some paintings such as The Key, Open the Mind and Open the Eyes employ earthy tones but are more abstract in the sense that they encourage viewers to be open-minded.

Yosifu acknowledges the importance of preserving Aboriginal culture through his artwork, but he believes that linking it to environmental concerns makes it more relatable to viewers.

“It is about speaking to people in a universal voice,” he says.

OUTSPOKEN VOICE

Yosifu says that his transition to abstract art was befuddling to some because prior to this year, his paintings revolved around colorful portraits of Aboriginal people.

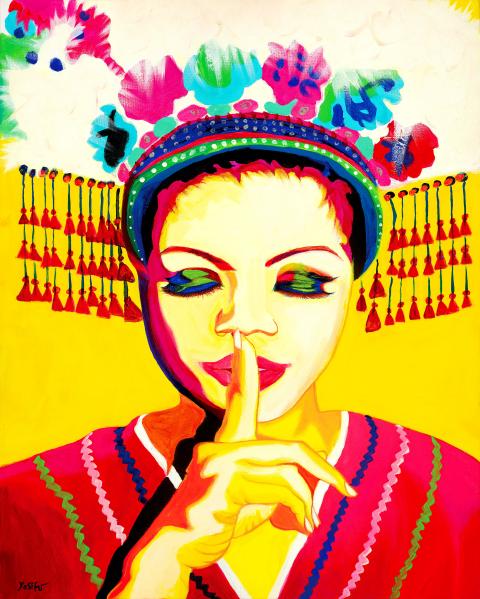

In 2010, his portrait of his friend Ado with her finger over her mouth was chosen to be on the poster representing Ban-Do @Formosa at the Candid Arts Trust in London. Entitled Can’t Speak (說不出), the piece is a critique of the government’s law prohibiting the use of Hakka, Hoklo and Aboriginal languages in Taiwan from the 1950s to the 1990s.

Unlike Hakka or Hoklo, which can mostly be written in the form of Chinese characters, Aboriginal languages are passed down orally.

“If you cut the language, you are cutting our cultural continuation,” Yosifu said.

Yosifu understands the importance of language preservation. Once a professional singer, he regularly holds dance and music performances at his gallery. A few weeks ago, he hosted a Maori festival in which he also sang.

“I like to make my gallery an energetic, open area for people to share their stories,” Yosifu says.

He adds that his artwork “ignites conversations and connects different people.”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) yesterday paraded its military hardware in an effort to impress its own population, intimidate its enemies and rewrite history. As always, this was paced by a blizzard of articles and commentaries in the media, a reminder that Beijing’s lies must be accompanied by a bodyguard of lies. A typical example is this piece by Zheng Wang (汪錚) of Seton Hall in the Diplomat. “In Taiwan, 2025 also marks 80 years since the island’s return to China at the end of the war — a historical milestone largely omitted in official commemorations.” The reason for its