Along Qingdao East Road (青島東路), the sharp points of a long fence are covered with tennis balls and pieces of cardboard, leftovers from the Legislative Yuan storming on March 18. Across the street, the wall is plastered with bright pieces of color: twisted balloons, lines of poetry, comic strips, posters and placards — memes that are spreading through student networks on Facebook.

Art has been central to the occupation over the cross-strait service trade agreement, in a scope and scale not seen in the day-long street demonstrations that have preceded it. This time, as days stretch to weeks, protestors have taken to writing, painting and producing other visual art. Work has accumulated on the wall as a kind of art exhibition that’s recording their time at the Legislative Yuan.

In the first few days of the student movement, most pieces originated from university clubs and professionals like Hunter Comics (獵人政治漫畫).

Photo: Enru Lin, Taipei Times

They were inspired by the sunflower, a heliotropic plant that students adopted as a metaphor for transparency. Other early works were caricatures of President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九), drawn in emperor’s clothing or with deer antlers, a reference to a moment earlier this month when Ma mistook deer antler velvet (鹿茸) for deer fur.

Early tropes also included appropriations from past protests. The raised fist, a symbol of resistance borrowed from overseas, clutches Taiwan in a large poster draped on the main building. The black-and-white thumbs-down fist, created for the “Depose Bian” movement (百萬人民倒扁運動) in 2006, appears on the wall with “Ma” substituting the name of the former president. There is also the eye of Big Citizen, popularized during the Citizen 1985 demonstration for the late Corporal Hung Chung-chiu (洪仲丘). This time, the eye is drawn on the face of the sunflower.

ART OF RECORD

On Friday, March 21, the movement entered its third full day and Legislative Speaker Wang Jyn-ping (王金平) didn’t attend a meeting with the president on coordinating a formal response. As the Associations of National Universities of Taiwan urged Ma to engage in talks with student leaders to defuse the situation, hand-drawn placards went up at the legislature, calling for the same. One depicts a horse (Ma’s surname can mean horse) with its head in the ground, captioned, “Ma: Don’t be shy.”

Most protesters were completing their masterpieces at a small space behind the party caucus offices at the Legislative Yuan.

Athice Kao (高詩涵), a professional designer, had pulled a plastic tarp over a granite platform. The drawing station, labeled Creative Connection Against the cross-strait service trade agreement (反服貿創作連線), offered paper, pastels, paints and other materials to passersby, mostly students.

These budding artists have a penchant for cartoons, like Batman (caption: “Taiwan does not have a Batman, but it does have you”), the yellow duck and the Formosan Brown Bear, used as a symbol of Taiwan.

“We ask them to avoid using inelegant language, but we don’t set other limits,” said Lin Yu-chih (林游智), 18, the volunteer in charge of the station.

As the protest drags on, the works have become darker. Near the art station, a drawing in marker shows a white road leading to a red perpendicular line, while a sign underneath reads Dead End. Another sketch shows anguished faces surrounding a mousetrap baited with money.

Lin is a freshman in finance at Yuan Ze University’s (元智大學) College of Management. He arrived at the Legislative Yuan on the movement’s second day and later joined the crowd at the Executive Yuan.

“We went because there was so much pressure. You are waiting for the government, sleeping here for many days and no one pays attention to you. When Jiang Yi-huah (江宜樺) came that day, we were eager but he didn’t address the concerns, he only said the pact was good. So my mood was very low. Everybody else was about to collapse,” he said.

After the police violently evicted protesters from the Executive Yuan, collages featuring images of bloodied bodies taken from the pages of The Journalist (新新聞) magazine and other local media went up on the walls.

“When the police got to me, they asked, ‘Do you want to get up?’ and they took me by the shoulder. When I exited, someone hit me across the back, but I didn’t turn around,” Lin said.

On Monday, March 24, Executive Yuan Deputy Secretary-General Hsiao Chia-chi (蕭家淇) said students had eaten his sun cakes during the occupation. New posters went up featuring the stolen cakes, including an image of the cake placed at the center of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s white sun emblem. Empty boxes of sun cakes were tied to the street lamps. Students photographed themselves eating sun cakes and embracing, a play on the word baomin (暴民), “violent citizens,” which is homophonous with “embracing citizens.”

A few days later, former KMT legislator Chiu Yi (邱毅) spurred new work with his on-air gaffe that students were using bananas as the movement’s symbol. The next day, bananas proliferated at the protest site, tied to the stalks of sunflowers.

‘YOU DON’T EVEN PROTECT YOURSELF’

This public exhibition is temporary, of course. It will be dismantled when the movement ends. Ask Lin, though, and he’ll say it won’t be soon.

“I’m going to stay here for as long as it takes to get results,” he said.

Lin stressed that good things take time: The main problem with the pact is how little time it took to negotiate and to pass, he said.

“When South Korea deliberated its FTA with the US, it took six years, and both sides could go back and revise, over and over.”

“With us and China, the entire process took one year,” he said.

“The US is afraid of China, too, because they are growing so economically dependent. The US is revising their laws to counter the effect. Yet everyone here is thinking, China is coming, we are going to do so well,” he said.

Lin, like many others in the student movement, fears that Taiwan will flounder under the pact’s terms.

“Say all the basketball teams in the world come together and play. We are not afraid of competing. But if we are 10 people playing against 100 people, how do we play?”

Lin echoed many protesters when he says that he is not afraid of competing. “But we need a regulatory system that protects us. You want to interact with someone who points so many missiles at you, and you don’t even protect yourself.”

In between running the station, Lin has done some paintings too. His watercolors of simple sunflowers are taped to the front gate of the Legislative Yuan. One is ringed by splotches of red, which he said represents the recent bloodshed.

“I also painted a sunflower in a background of black,” Lin said. “It means we’re going to be a small light burning in the darkness.”

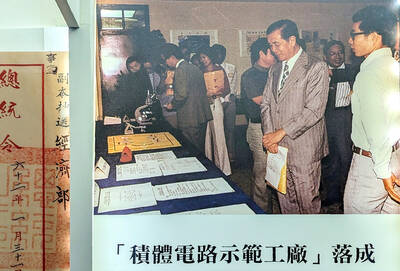

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,