Behind a vibrant green lawn and luxuriant trees, the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum sits quietly in the southwest corner of the 228 Peace Park. The museum is one of two in Taipei erected to commemorate the 228 Massacre (also known as the 228 Incident) and a must visit place for individuals hungry for knowledge of Taiwan’s modern political history. The 228 Massacre and the subsequent slaughter remains the nation’s worst mass killing.

Originally inaugurated on Feb. 28 1997 on the eve of the massacre’s 50th anniversary, the museum closed for renovations in April 2010, and reopened a year later with new permanent exhibits. However, controversy emerged as the newly-minted museum and exhibition drew harsh criticism from victims’ families, academics, political activists and opposition parties. Critics said the new museum, which had been under the management of the Taipei City Government’s Department of Cultural Affairs under then-mayor Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) since January 2003, glorified and whitewashed the acts of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and distorted the truth with its selection of displays and documents.

Lee Te-cheng (李德振), for one, said that the new exhibits didn’t accurately depict the historical truth. The grandson of former Taipei City Council member and massacre victim Lee Jen-kuei (李仁貴) said he couldn’t accept the exhibit’s narrative in how it “portrayed the government’s action as merely ‘exercising government power’ and ‘restoring order.’”

Photo: Ketty W Chen

Following protests by Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Taipei City Councilor Chien Yu-yen (簡余晏), former Memorial Museum director Yeh Po-wen (葉博文) and former Academia Historica president Chang Yen-hsien (張炎憲) — who went through the exhibition with the museum staff and identified the historical discrepancies and erroneous descriptions — the wording of some displays were changed.

While there has been an improvement in the language used to describe the events leading up to the 228 Massacre and the succeeding killing in the following months, the 228 museum still needs to more effectively present the atrocity in the context of Taiwan’s modern history and to explicate those ultimately responsible for the worst atrocity in Taiwanese history.

Additional and supplemental explanations should also be put in place to elucidate the extent to which the 228 Massacre marked the beginning of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) authoritarian regime and the White Terror Era, which remains the defining event in the political divides that exist in Taiwan today. Still, the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum serves as a good and reasonable starting place for those who want to understand Taiwan’s history and a venue for those who disagree with the city government’s interpretation of history to identify the discrepancies and provide the appropriate corrections.

Photo: Ketty W Chen

the Museum’s Architecture

The new 228 museum emits a modern ambiance compared to its predecessor. Instead of white florescent spotlights, studio lights with yellowish and warmer hues are installed throughout the museum with spotlights highlighting each exhibit and artifact.

Audio guides in Chinese, English and Japanese are available at the museum information counter free of charge. However, prior knowledge of Taiwan’s history is necessary because the narrative doesn’t clearly identify which display or historical documents the visitor should pay attention to.

Photo: Ketty W Chen

The museum has two levels, with exhibits divided into seven sections. The first section discusses the museum’s former usage as the Taipei Broadcasting Bureau and the history of Taiwan’s radio stations. But only towards the end of this section does the visitor realize its significance: that protesters demanded authorities broadcast throughout the country the shootings and subsequent protests taking place in Taipei.

The museum then backtracks in history with the second and third sections on the Japanese colonial era, Taiwanese demand for autonomy and equal rights and World War II — all told through the perspective of the Republic of China (ROC). The exhibit depicts, through old newspaper clippings and other publications, the Taiwanese endeavor to lobby for more political rights from the Japanese government. Documents and artifacts of the Kominka Movement, the Japanese endeavor to make Taiwanese loyal subjects of the emperor, are parts of the exhibit. The ROC perspective is also evident in a display under the title Running for Shelter during Air Raids, as the description of a painting reads, “Even though Taiwan has never been a full battleground, the planes of the enemy country of Japan still inflicted damage at will.”

This section concludes with the end of World War II and offers explanations on the dual identities of the Taiwanese, one of which is Japanese and the other waiting eagerly to be part of “the mother country.” According to the exhibit, the Taiwanese were greatly disappointed by the arrival of Nationalist troops, with discriminatory employment and language policies enacted by then-governor Chen Yi (陳儀) and rampant corruption being the primary sources of resentment.

The exhibit does not mention, however, the social, cultural and attitudinal differences between the Mainlanders and the Taiwanese, which was also cause for much resentment. Up to this point, there is no mention of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his role as the chairman of the Nationalist Government of China. At the end of the exhibit, there is an interactive game, where visitors can complete a puzzle of Taiwanese political cartoons.

The 228 Massacre and Village Cleansing

The museum gives a detailed account of the event that triggered the country-wide protest. Taiwan Tobacco Monopoly bureau inspectors confiscated vendor Lin Chiang-mai’s (林江邁) contraband cigarettes and her money. As Lin begged for leniency, one inspector hit her over the head with his pistol, causing Lin to fall to the ground while bleeding from her head. Bystanders came to Lin’s assistance and pursued the inspectors. One inspector fired his gun as he escaped and accidentally killed a bystander. The gathered crowd then marched to the police station, and demanded the arrest of the killer. Police did nothing and the Fourth Division of the Military Police harbored the inspector all night.

On the morning of Feb. 28, protesters took over the Taiwan Tobacco Monopoly Bureau, entered the Taipei Broadcasting Bureau and announced to the rest of Taiwan that protests had broken out in Taipei, sparking country-wide protests in major cities.

The initial chaos wraps up the first part of the exhibit. Visitors to the museum can then take the stairs to the second floor. The 228 Massacre itself, the arrival of the 21st Division of the Nationalist military through Keelung and the consequent village cleansing (清鄉) that subsequently ended on May 15 form the first part of the exhibit on the second floor. It is here on the second floor that the museum has its most powerful yet controversial exhibits.

The narration describes Taiwan governor Chen Yi as the main culprit, along with Peng Meng-chi (彭孟緝), the garrison commander, who gave the order to the military to attack the train station, the Kaohsiung Middle School, the Kaohsiung Municipal Government and to shoot all the city councilors, who were in the process of negotiating a settlement for the 228 Massacre.

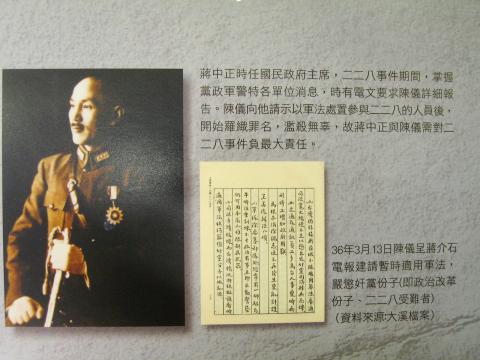

One small photograph of Chiang Kai-shek is displayed, along with a request from Chen Yi requesting military assistance, while another document is of an official order from Chiang on March 1947 banning the military from taking any revenge against civilians. Critics of the museum argue that Chiang played a much larger role in spearheading the military crackdown and accused the museum of attributing responsibility to Chen Yi, while minimizing Chiang’s responsibility.

The museum does identify, though, Chiang Kai-shek and Chen Yi as mostly responsible for the initial brutal crackdown and the later killings. This section presents examples of arrests, interrogations and methods of execution of protesters and elites by KMT troops.

The Victims

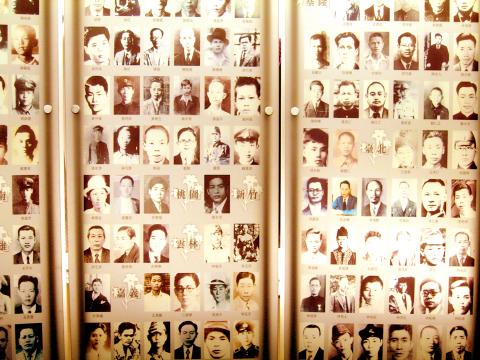

The last section of the museum commemorates the victims of the 228 Massacre and their families. The exhibit titled The Suffering displays on a circular glass wall photographs of the victims. The exhibit also identifies some influential Taiwanese leaders who either disappeared or were executed by the KMT, including renowned painter and a member of the Chiayi City Assembly Chen Cheng-bo (陳澄波) and Wang Tien-teng (王添?), a member of the Provincial Assembly.

An interactive program enables visitors to look up a victim’s name and listen to the testimony from their family members about the suffering they endured. The testimonies are very moving and helpful in painting a more complete picture surrounding the 228 Massacre. Visitors are encouraged to leave their thoughts and reflection on a bulletin board.

Assessing the 228 museum

The permanent exhibition at the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum serves as a good starting point to understand Taiwan’s modern political history. Along with the multi-language audio guide, there are also a number of very capable and multilingual museum tour guides, who are more than happy to show visitors around and answer any questions. The interactive games, however, are redundant and serve no particular purpose and can even be seen as making light of the tragedy.

The museum fails to fully conceptualize the significance of the 228 Massacre in Taiwanese history, and the permanent exhibition needs additional presentation to elucidate the extent to which this tragic event marked the beginning of the White Terror Era, where even more individuals were arrested, jailed and executed. The White Terror Era is still something that many members of the older generation in Taiwan refuse to discuss and speak about. It seems doubly odd in light of the fact that so much space is expended on the Japanese colonial era, a time that is, at the most, tangentially related to 228. These critiques aside, the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum does possess the qualities of a quiet, somber place for contemplation. Individuals of all ages who are interested in learning about Taiwan are strongly encouraged to pay a visit.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.