“Satire,” in the words of Broadway showman George S Kaufman, “is what closes on Saturday night.” But at least Lucy Prebble’s Enron, with its satiric view of American capitalism, made it through to yesterday, when it closed prematurely at New York’s Broadhurst Theater. The news may be shocking, but it’s not that surprising, given three factors. One is theater critic Ben Brantley’s obtuse and hostile review in the New York Times. Another is the aesthetic conservatism of a theater culture that likes plays to be rooted in the realist tradition. I suspect there is also a lingering suspicion of a young British dramatist’s right (Prebble is in her 20s) to tackle a profoundly American subject.

Enron, as theatergoers who have seen it at Chichester, the Royal Court or in London’s West End will know, is a hugely ambitious play. Spanning a period from 1992 to 2001, it shows how the Texan energy giant moved from a model of the future to a bankrupt disaster with debts of US$38 billion. That was largely because its CEO, Jeffrey Skilling, was a Marlovian over-reacher, more interested in trading energy than supplying it. As profits tumbled, Skilling turned to his sidekick, Andy Fastow, to create shadow companies to camouflage mounting debts. In Rupert Goold’s brilliant production (he directed both versions), this complex maneuver is illustrated through a series of Chinese boxes, illuminated by a flickering red light symbolizing the minimal basic investment: capitalism, in short, as con-trick.

The play opened in New York on April 27, and there were plenty of positive reviews from US critics. “Whip-smart, edge-of-your-seat,” wrote the New York Post’s critic; “surprising, remarkable, utterly thrilling,” thought the New York Observer’s. But Enron’s fate was sealed the moment Brantley’s review appeared, the day after opening. His first sentence described Prebble’s play as “a flashy but labored economics lesson,” and you could imagine potential theatergoers deciding to save their dollars and settle for a night at the movies. And while, as a fellow critic, I respect Brantley’s right to his opinion, what is dismaying is his failure to see what Prebble and Goold were up to. Far from being a flashy distraction, the play’s vaudevillian style is a visual embodiment of the dreamlike illusion to which the Texan energy giant, and similar corporations, surrendered.

But no serious play on Broadway can survive a withering attack from the New York Times, which carries the force of a papal indictment. It is also a situation that is rarely challenged. One of the few people to take up the cudgels was David Hare when his play, The Secret Rapture, got a similarly dusty reception from the then New York Times critic, Frank Rich, in 1989. This led to an acrimonious public dispute that prompted the memorable headline in Variety: “Ruffled Hare airs Rich bitch.” But what I recall most is a letter Hare addressed to Rich, saying: “Frank, you are lord of all you survey. What a pity it turns out to be ashes.”

Brantley was not alone in his dislike of Enron. “Heavy on sizzle, light on steak,” said the Daily News. “If you’ve seen the news ... the play won’t offer up much in the way of insight or illumination.” New York magazine deemed the play “good, dumb fun — though little more than that.” One reason for the attacks is the entrenched American view that visual pyrotechnics and razzle-dazzle are the province of the musical. Plays, on the other hand, are judged by their fidelity to what a critic once called “the visible and audible surfaces of everyday life.” It’s permissible for Wicked or Legally Blonde to deploy expressionist techniques but, on Broadway at least, plays are expected to conform to the realist rules.

With the exception of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, I can think of no play that has successfully violated that tradition. It is notable that when writers such as Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee grew more experimental with age, they were quickly kicked into touch. What hope had Enron with its demon-eyed raptors, Jedi knights and Siamese twins?

But Brantley does make one valid point when he says that the public memory of the Enron scandal “grows fainter with each succeeding account of large-scale financial misconduct.” With America currently gripped by the story of alleged misdeeds at Goldman Sachs, it may be the Enron story seems like old news. Yet this could also work the other way. What with the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the Bernie Madoff scandal, you would have thought New Yorkers might have been willing to give house room to a play that points out our complicity in financial bubbles, and which argues that lessons have still to be learned. But I suspect there’s more than a touch of chauvinism in the rejection of Prebble’s play. After all, if the Royal Court presented a US play about the collapse of Northern Rock, how would we react?

Other factors may explain Enron’s swift demise. Bombs around Times Square can’t have helped. Enron’s failure to be nominated for any of the major Tony awards, Broadway’s annual school prizegiving, was also the kiss of death (it was shortlisted in the sound, lighting and original score categories). I also can’t help wondering if the production would have fared better with its original London cast. Norbert Leo Butz, who played Skilling, is, to judge from his performance in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, a figure of dynamic comic energy; I doubt, however, he has the Shakespearean gravitas Sam West brings to the role in London.

If Enron’s melancholy saga proves anything, it is Broadway’s irrelevance to serious theater. Musicals, as the success of the Menier Chocolate Factory’s La Cage aux Folles and A Little Night Music at this week’s Tonys proves, are its stock in trade. There might be room for one decent, straight new play, as shown by the current popularity of John Logan’s Red, which originated at the Donmar and is also nominated for the big awards. But at heart Broadway is a big, gaudy commercial shop-window, where fortunes are won and lost.

I’ve long said the beating heart of US theater is in Chicago, from which two terrific new plays, Tracy Letts’s August: Osage County and Lynn Nottage’s Ruined, recently emerged. In fact, next time an ambitious producer thinks of taking a London hit play to Broadway, I’d suggest they ask the question that used to adorn posters in wartime: is your journey really necessary?

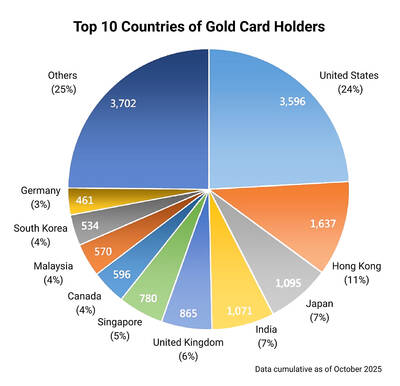

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

The Western media once again enthusiastically forwarded Beijing’s talking points on Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s comment two weeks ago that an attack by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Taiwan was an existential threat to Japan and would trigger Japanese military intervention in defense of Taiwan. The predictable reach for clickbait meant that a string of teachable moments was lost, “like tears in the rain.” Again. The Economist led the way, assigning the blame to the victim. “Takaichi Sanae was bound to rile China sooner rather than later,” the magazine asserted. It then explained: “Japan’s new prime minister is

NOV. 24 to NOV. 30 It wasn’t famine, disaster or war that drove the people of Soansai to flee their homeland, but a blanket-stealing demon. At least that’s how Poan Yu-pie (潘有秘), a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw in what is today Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), told it to Japanese anthropologist Kanori Ino in 1897. Unable to sleep out of fear, the villagers built a raft large enough to fit everyone and set sail. They drifted for days before arriving at what is now Shenao Port (深奧) on Taiwan’s north coast,

Divadlo feels like your warm neighborhood slice of home — even if you’ve only ever spent a few days in Prague, like myself. A projector is screening retro animations by Czech director Karel Zeman, the shelves are lined with books and vinyl, and the owner will sit with you to share stories over a glass of pear brandy. The food is also fantastic, not just a new cultural experience but filled with nostalgia, recipes from home and laden with soul-warming carbs, perfect as the weather turns chilly. A Prague native, Kaio Picha has been in Taipei for 13 years and